During the summer of 2009, Esteban participated in an anthropological study of the Wayuu people. His ethnographic investigation focused on the dynamics of ethno-education in an indigenous local setting, their effects on culture and people and its role in the construction of a modern multicultural Colombian state and in the lives of the Wayuu people.

The Wayuu people inhabit the semi-arid Guajira peninsula in northern Colombia. The Wayuu represent 20 % of Colombia’s total Amerindian population and 48% of the population living in the Department of La Guajira, a peninsula in the northeast region of the country.

But now it is not just their territory that the Wayuu people are fighting for. As globalization continues to creep across the world, and into Columbia, the Wayuu people are in danger losing their cultural heritage and traditional knowledge.

The Wayuu people were co-opted into the modern society and resisted by forming indigenous organizations. They live on a collective territory, with their sovereignty recognized under Colombian law. However, they often come under pressure to abandon their land, which is given to multinational corporations by the government for economic exploitation. The Wayuu feel that they have been abandoned by a state that did not care to protect their cultural and natural heritage, as well as their ancestral lands.

Guajira, the Wayuu, and Coal

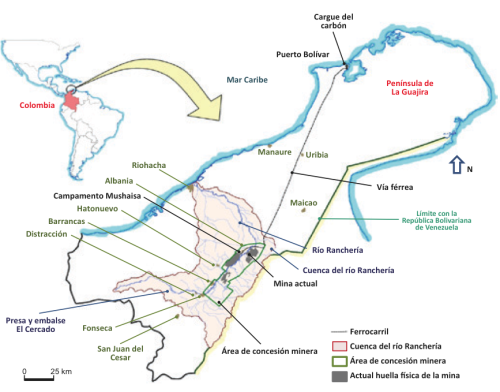

In the last thirty years, El Cerrejón, now owned by the multinational companies Xstrata, BHP Billiton, and AngloAmerican, has only been periodically questioned about its impact on the communities living nearby. Only a few articulate activists defended the interests of the local Wayuu Indians. But the seven billion dollar open pit mining venture has drastically affected the well-being not only of the Wayuu people, but also that of local farmers and afro-Colombians in the Guajira department.

The owners of the mine, with the support of the Colombian government, aim to divert the Ranchería river channel by 26.2 kilometers (or around 16.3 miles) to extract more coal under the riverbed. In a semi-arid climate, diverting the only river would seriously impact nearby territories, ecosystems, and their inhabitants. However, those running the mine try to deny the impact diverting the river would have on the community and the land – and spend millions to publicize their “responsible mining” practices.

As an adolescent Esteban had visited the mining region. But as an adult familiar with the area’s ethnography he was able to understand the impact the El Cerrejón Coal Mining Project has on surrounding communities. Esteban admired the collaboration of unions, afro-Colombians, farmers, and Wayuu people protesting the mining company’s plan to extract more than 500 million tons of coal under the riverbed.

With this in mind Esteban, now a graduate student in Latin American studies at UC San Diego, spent this past summer in Colombia living in different reguardos in the southern part of la Guajira. He also worked and collaborated with local organizations to protect the Rancheria River. The Wayuu consider the river to be sacred as it is part to their connection to woumainkat (mother earth).

Local inhabitants (Guajiros) and Wayuu’s organized their local economy around agriculture and trade. In the last thirty years, the government’s effort to pursue ownership of the land and the creation of resguardos (reservations) was in fact a way to get local inhabitants off the land. The government’s partnership with multinationals drastically changed the local landscape. The multinationals were granted access to coal, but they did not compensate local farmers and Indians for the loss of their way of life. The railroad and the coal extraction process increased the traffic and population in the region.

Access to the pit and the mining territory is strictly forbidden for the local Indians and farmers, who lament their lack of freedom. Most days, at 12:45 pm, earth-shaking vibrations occur due to massive explosions from the mine. Workers intend to minimize the noise and the explosions when foreigners are visiting the region.

Esteban, influenced by his background in ethnography, sees the resistance not only as a fight for the land but also as a fight for life. Esteban locally took part in a movement that went beyond barriers of class, gender and race. During this summer Esteban participated in two major protests to preserve the river’s natural trajectory.

Through the Comite Civico de la Guajira, he participated and helped organize a march on August 1st. The march took place in Riohacha, Colombia as part of a larger movement across the country to protest against mining policies and their destructive impact on the environment. Esteban witnessed approximately two thousand people attending the march in Riohacha.

After marching around the city, the protesters gathered in a park to talk about the river and how crucial its protection is. The mining company’s owners reminded the activists that diverting the river is only a potential project. However, Esteban is convinced that they will still try to exploit the coal located under the riverbed.

Later, on August 16th, Esteban helped to raising funds and led one of the six commissions that traveled down the river and to visit the communities living nearby. This expedition represented a great effort by the diverse people of Guajiro to unite against the mining company and the state. Beyond a fight for the land, the resistance aims to unite and educate people to better use their political rights to protect their heritage. Esteban, influenced by his background in ethnography, sees the resistance not only as a fight for the land but also as a fight for life.

Esteban expects the river to be saved, and continues to write both ethnographic and activist texts to raise people’s awareness on this important issue. He also hopes to show that new form of oppression are at play at the local and global levels.

Organizations mentioned in this post:

El Comité Cívico de la Guajira

AACIWASUG (Asociacion de Autoridades Tradicionales y Cabildos Indigenas Wayuu del Sur de la Guajira), and Fuerza de Mujeres Wayuu.

Other Links:

Photos courtesy of MSU by Kelly Gorham, Wikimedia user Foj333, Tanenhaus (Flickr: Rancheria Wayúu), Flickr user Tannenhaus jtanenhaus.com