Katherine nodded and turned back to the warmth of her fire.

Over Thanksgiving in 2010, I was one of 120 people from across the United States who joined the Black Mesa Indigenous Support Caravan to help the Navajo elders living on this remote wedge of land in northern Arizona prepare for winter. For a week, we cut and delivered truckloads of wood, as well as warm clothing and groceries, repaired hogans and livestock corrals and herded sheep for winter forage. The elders here were traditional Navajo, living in single-room houses without electricity or running water, weaving, raising livestock, and maybe owning an old truck to navigate the rutted dirt roads of the reservation. And yet for nearly forty years, these people, as spare and sere as the land itself, have been resisting the combined efforts of the Hopi and Navajo Tribal Councils and the U.S. government to force them from their homes.

Big Mountain lies between the rocky spine of the Hopi Reservation and the sprawling landscape of the Navajo Reservation, hooded by the coal-rich geologic formation of Black Mesa. It is part of a Delaware-sized area known as the HPL, or Hopi Partition Land, even though for generations it has been mostly occupied by Navajo. For decades, the struggle over the HPL has unfolded, steeped in history, myth, prophecy and the inevitability of greed – indigenous peoples set against each other as they were sucked into the industrialized world; of sacrifice, humiliation and dignity; and the lust for fossil fuel extraction played out against those who hold the skin of the Earth sacred.

We gathered inside the dome, now covered with tarps and plastic. The elders sat on chairs and the volunteers crowded on the dirt floor; we all huddled as close as we could to the rusted oil drum in the center where a fire blazed. A broad-chested Navajo man translated for us, the middle generation between the old and the young. He told us, "We talk only the truth to the fire," as the wind rattled the walls with incredible force. The Navajo women wore long skirts down to their ankles, velveteen blouses and sprays of turquoise and silver jewelry under wool coats. They spoke with a mixture of sadness and humor, often laughing. One woman, her face a cascade of wrinkles and legs shaking, apologized that she had to speak sitting down, or else she would fall over on top of the volunteers.

They told stories of animals taken away and fences put up across the open range. Their cemeteries were bulldozed, corrals knocked down. They had endured clashes with Hopi rangers, with little assistance from their own Navajo government. Behind the elders was an ironic casino banner proclaiming "Cash and Bonuses. Win $30,000." Through the hole in the roof for ventilation, bits of hail lit the early darkness like stars.

Katherine Smith spoke in a strong voice and thanked us all for coming. "We live in sad times. You have not forgotten us." Then she sat back, her eyes half-closed, maybe remembering how she helped spark the first active resistance on Big Mountain. In 1977, when a Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) crew arrived and started putting a barbed-wire fence across her land, Katherine grabbed her .22 rifle and fired over their heads.

The tribes faced other threats to their way of life. The Mormon Church planned to populate and establish Deseret, its own theocratic state from Canada to Mexico. From their base in Utah, Mormon settlers were pushing south into Arizona, acquiring land and trying to convert the indigenous people living there. Their missionaries were more successful converting the Hopi than the Navajo, but neither tribe truly had interest in becoming Lamanites – the Mormon name for Indian converts.

During the late 1800s, compulsory education was mandated for the tribes, with Navajo and Hopi children kidnapped from their homes and taken to boarding school compounds. In 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed an Executive Order establishing the Hopi Reservation, which was not, however, set up to deal with any dispute between the Hopi and Navajo, who for generations had lived peaceably together. The myth in American history books is that these two tribes had a long-seated animosity toward each other. However, even records from our own federal government indicate that their cultures intermingled freely and with friendship.

The blessing (or perhaps the curse) of the dry mesas and hollow canyons of Indian lands in northern Arizona is that they sit on top of one of the richest fossil energy resources in the United States. Petroleum, natural gas, uranium – and coal. As early as 1909, the U.S. Geological Survey had estimated there were at least eight billion tons of recoverable coal under Black Mesa; by 1970, the Arizona Bureau of Mines had adjusted this amount to more than twenty-one billion tons, as well as all the other untapped mineral potential. It was no wonder that in 1933, the BIA started receiving inquiries from oil companies as to who owned that mineral estate, a question that raised a considerable ruckus. Was it the property of the Hopi, as allotted by the 1882 Executive Order, or to be shared by the Navajo, who had continuously been occupying the land? Or did the mineral rights belong to someone else entirely?

When survey teams first sniffed the black bile of the earth, everything changed for the indigenous people living there. Both the Navajo and Hopi regard the boundary between their reservations as sacred, the place of their emergence into this world. It has nothing to do with historical immigration: where they are is where they have always been, in relation to the land that is their source. The need to geographically slice, fence, divide, measure, allocate and put a price tag on acreage was completely foreign to the traditional ways of both tribes.

But it was the way of the future.

Want more? Read part 2 here!

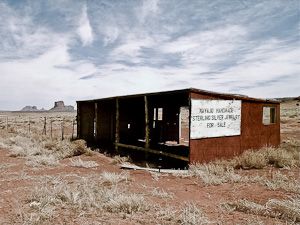

Photos are copyright protected and may not be reproduced without permission. Copyright information for images are as follows: 1) View from Black Mesa, photo courtesy of ctweney and used with the permission of Flickr Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0 Generic; 2) Navajo Jewelry Stand, photo courtesy of Angus MacRae and used with the permission of Flickr Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0 Generic; 3) Navajo Home, photo courtesy of the National Park Service and used with the permission of Flickr Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0 Generic.