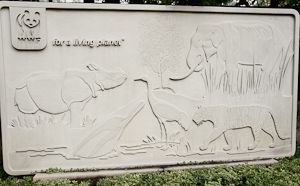

It was a hot, busy December afternoon in New Delhi as I entered the shaded, terracotta gates of Lodhi Estate. This is where the Indian headquarters of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is located, made immediately recognizable by a stone sculpture carved with the unmistakable silhouettes of the Bengal tiger, one-horned rhino, and freshwater Ganges River dolphin. These would be considered by WWF to be priority species due to their endangered status and importance to the heath of their respective ecosystems. In the lobby stood a worn statue and painting of the Hindu god Krishna before a lotus flower and an inscription that read:

In his time, Sri Krishna is said to have been responsible for restoring the ecological balance and conserving the environment in all of its facets…The space between the five lotus petals shows the five favored plants of Sri Krisha: Tulasi, Kadamba, Tamal, Pipal, and Mango.

Here in this program, our main role is to provide support to our various field programs, which largely focus on integrating conservation practices and livelihoods. Conservation is essentially a social process, especially in India. When we are working in the field to conserve habitat or species, it is really important that we work with communities, also. Similarly, we also try to build relationships with other like-minded NGOs and try to scale up our work, look at what lessons we can learn from others, and what we can do better. Similarly, we can share our experiences with others.

Because India is a country with many, many languages and diverse local communities, we need people in the field, also. I would say we at headquarters sit here and do pretty mundane stuff, and it is our colleagues in the field who actually face the challenges, do the actual work and also deak with some frustrations at times! Here, we are just the back support. We provide all of the possible support and look at policy issues, as well as other processes that can be used for our work.

I took a sip of my spicy, creamy tea and I asked Uppal to describe what sparked her individual interest in environmentalism.

I was brought up in one of the most backward states of India, then went on to do schooling in Delhi, and did my master’s in Mumbai. I am actually a nutritionist by training. When I graduated, I looked around to see what interested me the most for a career, and what really engaged me is how poor people are so dependent on the forest for food, especially during drought when there is nothing in the fields. People ate tubers and roots; what we used to call weeds were actually a source of food to others. So I started working on something called the Human-Nature Interaction Project, which looked at how people depended on the forest and the impacts of forests on people –

In your department and current role at WWF-India, what would you say is your number one conservation priority?

I think probably in this context, the most important issue is how to ensure that conservation and communities go together. Specifically, there are issues and different priorities in each region where we work, but the larger issue is how we can get communities and conservation to work together – it is the biggest challenge and concern.

A main part of that process must be to make sure that development is not sacrificed for the cause of conservation.

Yes, and it is a different situation for everyone. We cannot say “no” to development everywhere. Similarly, we cannot overlook people’s dependence on forest resources. One has to address that. One cannot ignore the fact that in some cases development is detrimental to conservation and peoples’ livelihood security. There are some realizations that need to be addressed.

Can you talk a little bit about the ways in which communities in India are dependent on forest resources?

I would say around 60-70 percent of the rural population depend on biomass [biological materials from living or recently living organisms, such as wood and grasses] for the main source of fuel. It is essential to cooking, boiling water and space heating. In some rural areas, dependence is as high as 98 percent. There are also many communities in particular areas that depend heavily on non-timber forest goods. They don’t depend on agriculture and are still traditional food gatherers. These communities depend on honey-collection and products like fruit, flowers, tubers, medicinal plants. A lot of it is used as for subsistence and some of it is used for income-generation.

I can give you a very good example of what we’ve done. In the state of Arunachal Pradesh, an area where the forest is owned by the community, WWF has worked with the Monpa community to create community-conserved areas. The community has set aside land with the primary aim of conservation and built a list of dos and don’ts about how to interact with and use the land, such as minimizing hunting and commercial extraction of timber. As an incentive and livelihood option, we have helped them set up community-based tourism initiatives. Capacity building, and local institution building has helped the community to manage and run the community based tourism. The community has set up homestays, home based restaurants and also mechanisms of benefit sharing. To ensure that this enterprise has a low carbon-footprint , WWF is helping the communities to use technologies like yak-dung, briquettes, and solar bathing systems to reduce their energy consumption, which did increase as more people visit the location as tourists. Currently, the community earns from the forests they are conserving instead of trying to earn from selling timber from it.

The most important aspect of eco-tourism is that the community benefits. It should be owned and managed by the community. I would not even call it eco-tourism but community-managed tourism. A lot of eco-tourism is done around the world but these initiatives often are set up by an outsider. I am not sure how many benefits of those businesses actually trickle down locally. I think that if an enterprise is community-owned and managed and actually benefits conservation and livelihoods, WWF should support such efforts.

What would you say to those in the West who see the effects of population growth on ecosystems in India as detrimental?

This is a debatable issue. I do see that population is looked at as a problem but I still think that the issue relates back to consumption and not population. If you look at a poor person’s impact, it is much less. A poor family of 10 here probably consumes as much as I or any other urban resident does.

Here, I brought up a journal article I had recently read about how a child in America consumes on average 120 times more than a child in Bangladesh.

If you look at that, I am not sure if we should focus more on population reduction/stabilization or reduce consumption. Providing food and water to every man, woman, and child – very basic things – are a concern. But I still feel that when you compare population and consumption, we need to be more worried about the current consumption pattern. Within the country I would say 20 percent of the people are consuming much more than the other 80 percent. Yes, the other 80 percent are more dependent directly on the resources, but they have no alternatives. One needs to provide the required opportunities/alternatives, plus access to better health services, population would probably stabilize after some time.

I told her that I often think about how consumption is such a socially embedded issue that has arisen as a result of capitalism and is considered a very positive attribute.She laughed at the apparent irony of my comment and agreed.

Yes, when you consume more, then you are a “developing” or “developed” nation.

So much of the challenge is transforming people’s minds and ideas about this assumption but a large part of it is also having policy in place and maybe even government restrictions. Can we talk a bit about what you are doing with policy initiatives for sustainable livelihoods in India?

I personally don’t really work with policy initiatives in terms of business but actually work with policy that asks who is bearing the costs of conservation and how we can provide incentives for conservation.

So, in your department what would incentives look like? Would they be financial?

Not necessarily. It can be financial, but it can also be land tenure rights, or having a stake in land management, and it depends on the situation and what stakeholders want. It could be a package. It may not be just one incentive but a basket of measures. Whatever it could be, the main thing to consider is how the benefits are shared and what mechanisms are developed, who develops them. At the end of the day, it is much more useful/powerful to have say over how your land is used than a possibly unreliable financial incentive that may not be relevant.

Would you say that the programs you oversee correspond with royal Bengal tiger conservation?

In fact, a lot of the areas where we work are crucial for biodiversity conservation. Habitat fragmentation due to improper land-use and unplanned infrastructure are increasingly threatening tiger populations and are at times more damaging than poaching. We look at critical tiger corridors and how they can be made more secure with the communities’ involvement. We also work with small local NGOs around protected areas that also have populations of tigers. We try to work together to showcase a sustainable livelihood model that goes hand-in-hand with biodiversity conservation. Community involvement can be in many forms like setting up informer networks to inform about poaching, using community to protect tiger habitats, also using community to protect tigers through monitoring the tiger movements etc.

One is having adequate resources/funding and having those for a long duration. When you are working with communities, it is a long-term commitment and we need to have a sustained engagement with them. Having the resources to commit to a community when they are willing to work with us is very crucial. Most donors want to see results that often need to be quantified. This may not happen when we work with communities. As non-governmental organizations, we can only make changes up to a certain point. We cannot replicate the government. But we can build bridges and help communities to access government resources. We can show the way and demonstrate something and if the government is proactive/receptive, they can replicate and scale up the successful models. The question we need to ask ourselves is as an NGO, “How much can we scale up programs ourselves?” The government can pick up a good idea and scale it up.

I was then escorted to the desk of Dipankar Ghose, director of the Species and Landscape program, who also agreed to answer a few questions about his work. I asked him how long he had been working here and the types of projects he oversaw.

When I joined WWF-India in 2005, I set up the Sikkim program office and worked on species conservation, wetland conservation, and capacity building of stakeholders in the forestry department. WWF works in eight landscapes throughout the country. [Last] year the landscape work was combined with species work.

So what exactly are the priority species in India?

Well there are, of course, three large mammals: the tiger, rhino and elephant. These are the three priority species in the foothills and the plains. In the hills, we have the red panda and the black-necked crane. The crane is quite threatened and the only species in the high altitude areas – the alpine and the subalpine zone – that indicates the health of the ecosystem to some extent. These are true transboundary species; India only has wintering habitats in northeastern India whereas the cranes breed in Ladakh[the northern tip of India] and Bhutan. In addition, we have the marine priority species: the Ganges River dolphin.

Curious about Uppal’s concern for wildlife corridors, I asked Ghose how corridors are managed within WWF’s priority landscapes.

The Terai Arc landscape is our second largest landscape, and it is also a 50,000-square-kilometer international landscape that stretches into Nepal. Within this area there are several national parks. Between some of the park parameters on the map you can see a lot of green space. Between other park boundaries, fragmentation is very apparent. In others, corridors are non-existent and impossible. Some elephant or tiger corridors have become very complex. The species need to move in very round-about ways to cross over into the park habitats in Nepal.

The mindset of people in each forest is different due to the industry that occurs there, be it mining or timber extraction, and many forest areas that are not protected are becoming more fragmented. There is a huge patch of forest which makes a good corridor in Terai Arc that is in good condition. Traditionally, this used to be a forest. Now, there is a road and a railroad line. This didn’t pose much of a threat to the wildlife, however. What happened was animals were coming here, mostly elephants and tigers. Over the years, an Indian oil corporation built railway tracks going into their infrastructure to transfer the oil. They put a 12-foot-high wall across the railroad tracks. The oil company was also approached by the border police of Tibet to set up a camp on their land. Now, not only is there a road to cross, but there also is a railway track, a huge wall and a military camp with many buildings.

We took it up with the environmental minister last year, and he called a meeting to suggest a resolution. We asked them to dismantle the wall and move the military camp either slightly northward or southward and allow the animals to travel safely through the nursery. By this time, however, it was too late as the people who had occupied the camp would need to be relocated and there were no funds to resettle 6,000 families. So, as you can see, the main threat to corridors is unplanned infrastructure.

I explained to Ghose that in the United States, our government was debating over the installation of the Keystone XL Pipeline, which would run from Canada all the way to Texas. Its proposed trajectory ran through fault lines, fragile ecological zones and numerous streams. Luckily, I said, the president has decided not to approve the pipeline as long as research concerning its potential for environmental damage remained unclear.

WWF takes research from academic institutions, such as the Wildlife Institute of India, a premiere wildlife institute in the country, and then we take that work forward and follow up the corridor issue with the respective authorities – whether it’s the forest department or if the land belongs to the revenue department–and ensure that corridors are restored and not destroyed. Conservation cannot always wait for science however. One of our people in the discussion group said, “Look, I have not seen an elephant in these parts in the past two years.” A corridor is a corridor; it is not meant to be used by an animal every day. Otherwise, it becomes a habitat. Luckily, a very senior officer in the forestry department said, “Even if the animal is using the corridor once in six years, it is still a corridor.” It helps with the genetic diversity of the species if a male happens to move to a new population; it saves us from having to relocate a male and improve the genetic diversity.

It isn’t just elephants here but tigers, also.

Ghose handed me a brochure entitled, “Status of Tigers, Co-predators and Prey in India, 2010: Executive Summary.”

The last estimation of tiger numbers in India was 1,411, which was done in 2006-2007. The latest estimate was in 2010 and the number is 1,706. This latest estimate does include two new areas, but even without the additional areas there was still an increase [in population] of 12-13 percent. That’s good, indeed, but if you look at the executive summary, you will see that although there are more tigers, the habitats have shrunk. The tigers are large mammals and have large ranges, but now they are pushed out from their regular habitats. There is more fighting between the tigers as they all move to the same reserves.

So, there must be an increase in human-wildlife conflict now also.

Yes, in terms of tigers, elephants and even leopards, the human-wildlife conflict in India is huge and on the rise.

Remembering Uppal’s comment, I asked, Would you say this has more to do with population growth or consumption?

Both. Population growth is linked with everything. But, if infrastructure is planned, we can make changes.We just cannot go out and tell people,“Hey, stop breeding. ”But if infrastructure planning is done in a better way, like for instance, if the oil corporation had been a little bit sensible and not constructed that great wall or not given that land to the police force…what we need here is better and more careful planning.

The classic example is this: in northeast India, there is an elephant reserve called Lumding Reserve Forest. It was late 2009 when we discovered that a road –a two-lane road up to 12-17 meters wide – passed through the elephant reserve and would be widened again to 60 meters. We said fine, as a conservation NGO we are not opposing the widening of the road. We recognize the fact that development is necessary, that there are pressures from rural communities to improve communication and

The information we have to go off of is very theoretical. You don’t know what is going to happen after ten, twenty years…whether the animal population will boom, or human populations will go down, or the amount of people on the road will go up – so based on the best knowledge we have of animal migration, traffic intensity and speed increases, we did some predictions and said that if we make it a 60-meter-wide highway, it will stop the movement of the elephants from one part of the reserve to the other. So, we suggested an elephant underpass in which portal type piers beneath the highway replace wall type piers, thereby providing lateral visibility and movement for the elephants.

So, instead of just being an activism organization, we gave a mitigation plan to the development team. Unfortunately, most of them have not been implemented.

Ghose handed me a thick pamphlet that provided details for planned infrastructure construction. It recommended building the highway while elephants are away on seasonal migration and installing features to attract elephants to the new, safer structure like water ponds, favorable grasses, and fresh elephant dung and urine. An image of an eco-friendly passage below a road bridge in Colorado was depicted as an example.

You would think that this project would be a win-win situation for humans and wildlife alike.

Unfortunately, that is not happening too much. No one implements most of the projects. And forget about animal safety! If a vehicle is moving at 60 miles per hour is hitting an elephant hard, then it is dangerous for all of the people on the road. From the human point-of-view, it is important we protect passengers.

Here, Ghose and I parted ways as he went on to attend a lunch meeting with other colleagues. I traveled to the gift shop in the basement, where I bought a few brightly colored handbags and charismatic stuffed animals fashioned by women in villages as a means to gain income from sustainable materials. As I left Lodhi Estate and made my way down the dusty yet shaded streets of Delhi to meet my own family for lunch, I couldn’t help but admire WWF-India for their tireless efforts in a country where roads have no rules, where rick-shaws, trucks, cars, and cows practice a frenetic ballet on the increasingly busy streets that are spreading exponentially like starfish across India’s diverse landscape. It is a country of immense contrasts, between the wealthy and the poor, men and women, alpine environments and arid plains. I hoped that on India’s chaotic, dynamic journey toward development, the incredible plant and wildlife biodiversity which Sri Krishna is fabled to have once held so dear would not one day become as incorporeal as its gods, or a stark contrast to the vision of India’s future.

Photos are copyright protected and may not be used without permission. Photo 6 is courtesy of Kathryn and Jonmikel Pardo; all other photos are courtesy of Altaire Cambata.