The pod of five dolphins gracefully, effortlessly, swims past me, perhaps a dolphin-length away. Entranced, I simply follow. Dolphins swim with powerful vertical thrusts of their tails, and for a few moments of rapture, I keep up, following the undulations of my fellow swimmers.

Hawaiian traditional healer and wisdom keeper Kahu Kauila Clark has told me to match my breath with the dolphins’ breath, as I would with humans when doing an energy-healing treatment. I know that dolphins breathe 3 to 12 times a minute, and must surface to do so. I consciously slow down my breathing through the snorkel, falling into the rhythm of the swim.

For that time, I feel a oneness with the dolphins. My two human companions and I are part of one pod with them. I feel at peace with the great ocean, and all fear vanishes in the delight of swimming in the wake of dolphins.

It was not easy for me to get to that place as I had a few fears to overcome first. Months before, when my friend and colleague Tara Waters Lumpkin, founder of Voices for Biodiversity, asked me if I wanted to swim with wild dolphins as part of a vision wellness retreat in Hawaii, it was a no-brainer: "When?"

On the first day of our two-day adventure, I’m a little worried. We see a whitecap-covered sea on our way down to the harbor and feel a stiff breeze as we reach the boat. I’m trying to feel confident as I sign a waiver. I have fleeting thoughts of sharks and decide, based on nothing, that the dolphins would protect us.

I’ve taken a homeopathic remedy for motion sickness, which has worked for me before and sort of works on these rough seas. I grit my teeth and hold on, bouncing as we cut through the rough indigo waves on our way north along the Kona coast to where — as another boat captain has told our captain, Kit — dolphins have been sighted.

I put aside my worries about the claustrophobic mask and snorkel. A snorkeling novice, I’m disconcerted by the need to remember to breathe through my mouth, which I practiced in a swimming pool the night before. I hadn’t even realized that we would need snorkels — I had had visions of swimming in the shallow crystal-clear waters of a cove close to shore with dolphins gently circling me.

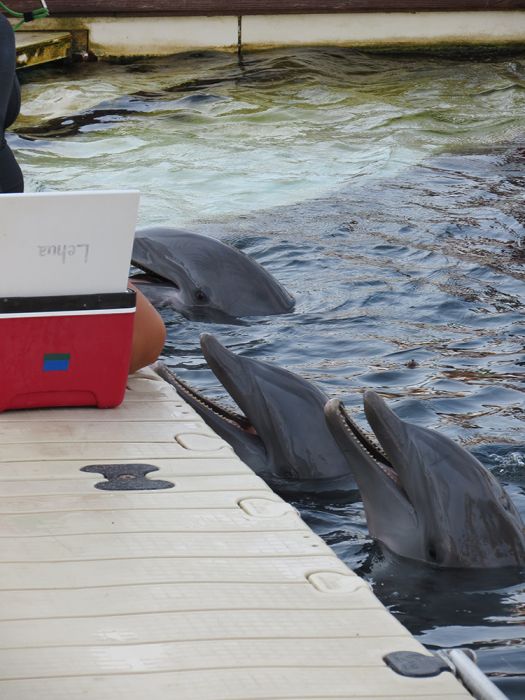

Jan Salerno, our dive master, is a font of information about dolphin habits. She presents it scientifically, occasionally slipping in something from the spiritual side. The spinner dolphins, she explains, are found closest to shore, the bottlenose a bit farther out, and then the spotted dolphins and the rough-toothed species, quite far from shore. Local dolphin swim operators have observed what many think are hybrid dolphins, the result of spotted and rough-toothed dolphins mating, and they hope to soon offer up proof.

What, I wonder, would it mean? What would cause interspecies mating? Warming of the oceans? Evolution driven by anthropogenic climate disruption? Acidification?

I enjoy just being close to dolphins, watching them leap beside our boat, unfazed by the heaving ocean. Divers on a nearby boat drop in as Kit and Jan watch anxiously. Kit has made it clear that no one in our group, though we range from novices to experienced divers, is going into that rough water. The divers don’t stay in long and struggle to get back on board their boat. Jan and Kit heave audible sighs of relief, and we head south.

A large pod of wild spinner dolphins. Photo credit: Kira Sadler

We won’t get to swim with dolphins today. My thoughts range from "Am I not worthy? " to "Darn it, I paid a lot of money for this."

We reach a somewhat sheltered reef edge, and Jan decides to take us all in so that those newer to snorkeling can practice. She and Tara are incredibly supportive as I overcome my fear of jumping off a boat into deeper water than I’ve ever swum in. I sputter a little bit as I prepare to put my face down below the surface of the water. Jan holds firmly on to my hand.

I discover a different world and understand why my Alaskan friends drag all this equipment on their winter vacations. It’s an alternate planet below the surface of the ocean, with drifting, filtered light and gracefully moving life-forms. Getting used to the rhythm of breathing, I squeeze Jan’s hand and let go. I float, timelessly, simply observing the colorful yellow and blue fish in this magical world of cathedral light.

Tara and I are both disappointed at the end of the excursion but try to put a good face on it. Surely the winds will let up tomorrow, and we’ll be able to find dolphins and swim with them. After all, we did get to see dolphins up close today, and that was fun, wasn’t it?

I text Kauila for advice, not knowing that this will be my last communication with him. He passed away two months later on Christmas Eve.

I fall into a pushy Western mindset mixed with New Age notions, asking, "Any advice about how to honor them and call them in?"

I’m really attached to that "calling them in" part, but Kauila replies, "The best way is to check their breathing pattern, and breathe with them as connective energy. Express gratefulness and be thankful."

I persist: "Should I just visualize connecting with them in a quiet cove?" I’m looking for some kind of teaching in calling them telepathically, willing them to come swim with us.

Kauila answers simply, "Don’t dictate. Just accept them where and how they are naturally."

I laugh at myself and surrender. Sure, I’ll still be disappointed if I don’t get to actually swim with dolphins tomorrow. But I’ll be OK. I won’t feel that I somehow offended them or failed to connect with them.

The next day, we all get our wish. The waves are calmer, and we soon find a pod of spinner dolphins willing to let us swim with them. This time, I let go of Jan’s hand quickly and watch in awe as she moves like a mermaid, diving deep and swimming gracefully with mothers and young ones. I take photos and video with my underwater camera, then leave it on board so nothing artificial can come between me and the experience. I wonder how the dolphins perceive us — is it as poor, awkward land mammals that need special equipment to swim and breathe in their underwater world?

Despite my unceremonious seasickness when I get back on board after the final swim of the day, I feel happy.

A week later, after the vision workshop, Tara and I decide to go again. The other people booked for the day cancel at the last minute, so it’s a private tour for Tara and me. The water is plankton-filled from the runoff of a heavy storm that passed through a few days before. But we quickly find many dolphins and though I am momentarily disoriented by the darkness of the murky waters and the fact that I can’t see the bottom far below, I soon gain confidence and am able to keep up with my pod of two other humans.

Today there are a lot more boats — and a lot more humans. They seem to be keeping a respectful distance from the dolphins as we were admonished to do. And there are a lot of dolphins. Many circle round and round a Belgian woman called Rainbow, who swims out into the ocean nearly every day and communes with the dolphins for hours at a time, warbling softly to them.

Our little pod sticks together. I remember to keep my hands close to my sides, to be more dolphin-like and not distract them with waving appendages. I slow down my breathing, as Kauila had advised, and I listen to and feel the echolocation clicks and chittering of the dolphins of the nearby pods. I’ve read in National Geographic that every dolphin "invents" a unique name or "signature whistle" in his or her youth and keeps it for life. Other dolphins call the individual by this name, remembering it for decades. I wonder if they have a name for humans, collectively or as individuals.

All too soon, the swims for the day are over. I haul myself back onto the boat for the last time, grateful for the privilege of observing wild dolphins in their own world, so very different from my land-based experience.

Later, my euphoria bubble will be a little deflated by people’s questions about whether it is ever ethical to swim with dolphins. I know that I would personally never choose to swim with captive dolphins, no matter how well they are treated. But surely swimming with wild ones is OK?

Tara and I discuss it candidly. We wonder if the noise of the boats irritates sensitive dolphin ears, if there are too many humans in the water, if we are bothering the dolphins. Jan and Kit are ethical operators, and Jan lays out all the rules about not touching or chasing dolphins, and talks about the Marine Mammal Protection Act. We are there as observers; though we may have interactions with them if they choose.

I read differing points of view and come to the conclusion that this experience is a sort of "sea safari" — not unlike viewing a herd of elephants from a car in South Africa’s Kruger National Park. Are the sputtering, polluting cars inherently disruptive to the wild animals? Are those animals, or the dolphins, truly wild anymore? Is this the price of collective humanity allowing them to survive, carving out bits of habitat sanctuaries in return for humans observing them?

The dolphins off the Kona Coast could easily swim away — but what if they really like that part of the coast and are just resigned to coping with humans most days? Anthropomorphizing and projecting, I wonder if they look forward to stormy, windy days when the humans won’t be out. Do they look forward to encountering their longtime friend Rainbow and her quiet singing? Do they view us as interlopers or playmates?

In the end, I feel peaceful with my choice. In an online blog with the disconcerting title The Selfish Connection: How Our Love for Dolphins is Killing Them, I read the author’s conclusion that swimming with wild dolphins in an ethical manner is not harmful to them. The piece has a great link to the Wild Dolphin Swim Code, developed in Mozambique, with a useful video of the do’s and don’ts.

Whether or not I ever swim with wild dolphins again, I feel great gratitude, as Kauila always taught me, for this momentary connection with creatures who don’t need humans, and who might be better off without us but accept us anyway.