"The economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment, not the other way around."

—U.S. Senator and principal founder of Earth Day Gaylord Nelsoni

It is difficult to imagine any real solutions coming out of Congress right now. There is an ideological divide, a rift, a lack of understanding on critical issues and the power of big money. But there is a larger question: Is the system we have in place capable of solving the problems we currently face? Our economic and global circumstances are changing rapidly with globalization, climate change, resource depletion, and a rapidly evolving economic system. For elected officials it seems impossible to adapt when we have crises of debt and unemployment. Yet based purely on the health of our ecosystems, it seems we are left with two choices: make these changes ourselves or have large scale changes inflicted upon us.

Economic growth has become synonymous with success, with freedom, with improvement, with the American dream. Yet, endless economic growth could ultimately be our downfall. Currently, we operate under a model designed for infinite economic growth. Our monetary system, our progress indicators, our investment structures; these are all based on the idea that our economy will grow forever. When there is no growth, there is unemployment, banks don't lend money, the economy does not innovate and we move toward collapse. Changing this foundation of our economy would be a leap from a cultural standpoint and a policy standpoint.

Economic growth is based on one central assumption: The economy is a closed system. This is a fundamental concept that comes from physics. A closed system is self-contained, having no inputs or outputs. This conventional model of the economy has a gaping hole: the ecosystem. In modern economic flow charts, we never see the input of resources or the output of detrimental factors such as pollution. In other words, there is no value on the ozone and no cost of species extinctions.

The Reality

In the 18th century, moral philosopher Adam Smith theorized on the free-market in the context of what economists call an empty world in which there were fewer people and nature was vast and plentiful. In that time period, the ecosystem could be entirely ignored and assumed to be infinitely abundant. Now, however, we are in a full world – a world in which population has increased ten-fold and consumption levels have skyrocketed. Though the economy has never been a closed system, this scientific fact has been historically ignored because natural resources were not yet scarce.ii Many of today's economists continue to assume that our economy is a closed system that contains an ever-substitutable supply of resources and pollution sinks.

While times are changing fast, the fundamental basis of our economy was born 200 years ago during the Industrial Revolution. During this time, the wealth of ecosystems was basically ignored, and economists considered man-made wealth to be the primary focus. As we destroy our natural resource base, we are destroying collective wealth and the resiliency of our economy for short-term private gain.

By assuming the economy is the whole and the ecosystem is merely a part, we are applying false economic precepts to the natural world. For example, in an ecosystem, not all parts and functions are substitutable; each segment has a unique niche that makes the system as a whole operate effectively. Through outright ignoring the physical dimensions of value, we are, in many cases, assigning value where we should not and neglecting to assign value where we should. We are calling losses profits and profits losses. Our economy does not completely reflect the values of the people, and therefore neither does the construction and destruction of the world around us.

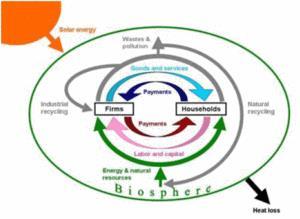

Here is an updated model of the economy

The conventional economic model does not include the biosphere, natural recycling, wastes and pollution, industrial recycling, energy and natural resources, or solar energy.

However, our economic system, based on this flow, interacts with our ecosystem on an inextricable level.

Our Debt in Natural Capital

In a paper published in Scientific American in 2005, ex-World Bank senior economist Herman Daly explains,

When the economy's expansion encroaches too much on its surrounding ecosystem, we will begin to sacrifice natural capital (such as fish, minerals and fossil fuels) that is worth more than the man-made capital (such as roads, factories and appliances) added by the growth.iii

The more we inhibit the environment, the less our economy benefits from these services.

Despite its limitations, putting a monetary value on nature can be highly useful and informative for both macroeconomic policy and conservation efforts. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) has estimated that each New Year, economic activity costs the world approximately 6.6 trillion dollars in environmental benefits. Expanding economic growth and inhibiting nature growth is actually quite costly, given that our entire economy depends not only on services nature provides – outdoor recreation, education, and health, to name a few, each of which provides significant income for both local and national economies – but also on stocks of natural capital such as timber and fossil fuels.

Pollution has created 246,048 square kilometers of dead zones in the ocean throughout the world. According to the Global Partnership for Oceans, approximately 35 percent of mangrove habitats have been lost in the last 30 years, which has had dramatic effects on the stability of coastal areas and increased negative impacts from storms on both local communities and ecosystems. This coastal wetland destruction may account for more than two percent of global CO2 emissions. Our current economy does not account for the benefits of healthy oceans, the services provided by mangroves or the economic benefits of a stable climate. It therefore cannot estimate the true cost of pollution. We have seen the tragic effects of rising ocean temperatures and climate change from Hurricane Sandy on the East Coast of the United States. From an economic growth perspective, Inger Andersen, vice president of sustainable development at the World Bank, notes that "without taking care of the environment we are shaving digits off GDP and, therefore, limiting our very potential for the future."iv

Of course, protecting nature not only has the potential to save dollars from national expenditures; it also seems to be a key component in creating a fair and just society. For instance, while many conventional economists have used the trickle-down logic to promote unrestricted free enterprise internationally, reports can now put economic values on the unequal distribution of costs caused by waste and resource extraction in economic activity. While ecosystem services may provide directly for two-15 percent of a nation's Gross Domestic Product (GDP), TEEB has found that this often affects the poor disproportionately. Internationally, the poor are more directly tied to the ecosystem, depending more on local resources and food for income while being less protected from the consequences of climate change and pollution. The societal neglect for natural capital may cost them as much as 50 percent of their wealth.v

Putting a monetary value on many basic ecosystem services illustrates the ecosystem service entitlements that corporations have been receiving. To a large extent, corporations have had the rights to destroy ecosystem services, pollute air and water, deplete resources, and harm the ecosystem at the expense of ecological flows and services for other producers and for present and future generations. A global calculation by Trucost for the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment estimated that the top 3,000 companies in the world, which account for 33 percent of global profits, cost the global public 2.25 trillion dollars per year. That's 2,250,000,000,000 U.S. dollars each year in externalities. Externalities are consequences of economic exchanges not captured by the economy. For example, the negative effects of acid rain not paid for by a pollution emitter are externalities.vi

National Security

The economy is not a purely economic issue, as the ecosystem is not a purely ecological issue. Climate change, rising sea levels, extreme weather conditions, droughts, resource scarcity, biodiversity loss, desertification; these are potential threats to life around the earth and potential threats to peace internationally. The U.S. military understands this, noting in their 2010 Defense Department review that climate change is an "accelerant of instability and conflict"; they identify climate change and energy security as "prominent military vulnerabilities."vii There is ample evidence that climate patterns such as El Nino are as much of a factor in civil conflicts as any other geopolitical or economic factor.viii Despite evidence from our own military, recent presidential candidates neglected to make the connection between national security and the environment in any of the 2012 election's three debates.

Signs Point Toward a New Model

Given current economic conditions, for a politician to denounce growth would practically appear as treason, especially considering the state of our economy today. A simple equation for a healthy economy is inadequate. As we evolve, so do our needs, our resources and our instruments. According to studies, economic growth has not correlated with our health and wellbeing since the 1970s. We no longer live in a period of infinite ecological abundance. Lastly, with evolving financial instruments, market instability – in many cases boosted by natural resource instability – threatens enterprise itself.

One example of an innovative next step is the OECD model for green growth. This may serve as a next step before the inevitable move to a regenerative economy. In June 2009, ministers from 34 countries, including the United States, signed a declaration stating that they will pursue green growth strategies, and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has provided a platform from which to work. In the introduction to the framework, OECD Secretary General Angel Gurria states:

If we want to make sure that the progress in living standards we have seen these past fifty years does not grind to a halt, we have to find new ways of producing and consuming things, and even redefine what we mean by progress and how we measure it. A return to "business as usual" would indeed be unwise and ultimately unsustainable, involving risks that could impose human costs and constraints on economic growth and development. It could result in increased water scarcity, resource bottlenecks, air and water pollution, climate change and biodiversity loss which would be irreversible.ix

"The United States, China and India have the largest ecological footprints... Large populations live in China and India. In both territories resource use is below the world average. The per person footprint in the United States is almost five times the world average, and almost ten times what would be sustainable."x

In Conclusion: Playing Catch Up

Even the Dalai Lama recognizes our stagnation. In his words, America is strong because of its freedom and individual creativity. Yet he humbly states, "Still, worlds change, so you should catch up." In fact, there is a growing list of countries statistically healthier and happier (at all income levels) than our own that also work with their environment to maintain a healthy future and resilient economy. It seems that if we wish to conserve what matters most, we must actively adapt to changing conditions. Now, progress and conservation go hand in hand. While political leaders struggle to find solutions for the pressing issues of the day, there is a growing undercurrent of desire for fundamental change. Our health and wellbeing does not need to suffer for economic growth, the wellbeing of our international community or the health of our environment. Using our current economic models, we are not including the work of insects, the organisms in our soil that help produce our food, the benefits of a stable climate, the ocean habitats that provide homes for the fish we eat, the planet full of water, air, plants and animals that cycle carbon and nitrogen, the roots that prevent erosion, or the solar energy that beats down day after day. History is filled with empires that fell due to changing climates and resource depletion. Perhaps the sooner we appreciate the finite and delicate nature of ourselves and our environment, the longer it will be until we are directly confronted by these truths.

Images are copyright protected and may not be used without permission. Copyright information for the images are as follows: 1) Circular Flows with Energy and Recycling, courtesy of GDAE, Tufts University; 2) Ecological Footprint, by Worldmapper.org.