My first job after moving to the United States from Norway was to work on recovery projects focused on salmon populations in California for the National Marine Fisheries Service. One day, my coworker asked me about Hucho hucho in Europe. Although I come from Europe, I drew a blank.

Salmon and trout are some of the most well-known fish worldwide. Their flesh is esteemed for its taste and consistency; it is found on menus of world-class restaurants. Salmon and trout are also the fish with capital F when it comes to recreational fishing, and it is one of the most successfully farmed fish, now common on the family dinner table all over the world.

Still, little attention has been given to the amazing diversity the salmon family of fish represents – and the peril this diversity is in. Few people even know that there are several species of trout and salmon; a regular restaurant menu will simply list “salmon,” despite the fact that there are six different species native to the United States alone. And each species varies in taste and consistency of their flesh.

However, more important than the diversity of species on the menu is the importance of these fish to people and their cultures. Where salmonids and people overlap, there has always been a strong connection between them. These fish not only represent food, but also a diversity of cultures, traditions and identities. Thus, when we lose the diversity of these fish, we lose not only fish, but also our own cultural heritage. Every salmon and trout has a story, and that story is about us.

As I learned more about the diversity of salmon and the threats it faces, I decided I wanted to see, and maybe taste, them all. In 2010, my fantasy started to become reality with the preparation and launch of The Great Salmon Tour, a project focused on recording and protecting salmonid biodiversity and exploring the relationships that people have to these animals. My goal is to show how a relationship between human beings and the environment has shaped our world's diverse human cultures.

The Salmon – an Example of Biological Diversity

To understand salmon diversity and human-salmon relationships, it is necessary to cover some of the basics of salmon taxonomy and biology. The salmon and trout we have on our dinner plates belong to a family of fish called salmonidae that contains more than 200 species of fish, all native to the higher latitudes of the northern Hemisphere. Within this area, they have a circumpolar distribution – meaning they are found in North America, Europe and Asia. Common names for the different salmonids are salmon, trout, grayling, whitefish and charr.

The term salmon has neither a taxonomic nor a biological meaning, but is a term that is used based on people's perception of what salmon are. In the United States alone we have six species we call salmon: king, sockeye, chum, coho and pink salmon – all of which are Pacific salmon (genus Oncorhynchus) – and, on the other side of the Cascades, Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). The fish we usually call salmon are anadromous: they spawn – or lay their eggs – in freshwater where the offspring then live for the first years of their lives. They then migrate to the ocean, where they feed and grow until ready to reproduce.

During the migration to the ocean they increase several fold in size, from a few inches to several feet long. Once they mature, they return to their natal river to spawn. The return is synchronized with a large number of salmon returning at the same time of the year – the salmon run. This provides a seasonal event with a high availability of large fish that are relatively easy to catch. Because of their marine phase, the fish contain important marine nutrients and a high fat content that are not usually available far inland from the ocean, making them an important part of the food supply for many predators, including people.

Native American Cultures and Salmon

In 2010, I left Washington, D.C., for the Tanana Village along the Yukon River. The people there are Athabascan, and the village is relatively small, maybe 300 people in the summer during the fishing season. Historically, families were partially nomadic and moved between different seasonal camps; adults in the village still remember the days when they moved around as kids. Today, though everyone lives in permanent structures, the salmon run still dictates a seasonal cycle in people’s lives.

In Tanana, fishermen still harvest three different salmon species during the summer season, each species having its own quality and use. Chinook salmon and summer-run chum arrive in mid-summer. Of these two, the Chinook salmon is used for human consumption, while the summer chum salmon is less attractive as human food and is harvested to feed dogs (hence the colloquial name dog salmon). By contrast, the higher fat content of the later fall-run chum salmon makes its flesh more appealing to people as a food source. Finally, there is the coho salmon, often preferred over Chinook because of its richer flavor and smoother meat.

Talking to villagers, I learned about the influences that salmon have on the social structure of the communities along the Yukon River. Knowledge and skills are transmitted across generations; a substantial knowledge and skill base is needed to be a good provider for the community. As such, I was told by Caroline Brown, an anthropologist for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, that many communities follow what is called the 30/70 rule for subsistence: 30 percent of the people in the communities feed 70 percent of the community. Thus, being a provider is a real responsibility that weighs heavy on one’s shoulders.

The social network created by sharing is more extensive in subsistence communities such as Tanana than in cash-based societies. The fishermen and women provide fish to immediate and extended family members, important people in their communities, people in need, and the elderly, confirming their ties to the community and reinforcing personal and family alliances. A loss of fisheries would also mean breaking the social fabric of these communities. Salmon are also an important part of their spiritual understanding of the world around them. As one villager in Tanana told me, distributing the first catch of the salmon run to others brings good luck and promises a good run the following year.

There is real concern, however, that this last bastion of the old way of living could disappear soon. The catches of Chinook in 2010 were the lowest in many years, and the number of fish in the run failed to meet the minimum number required to maintain sustainable populations, according to the U.S.-Canadian Yukon River Salmon Agreement under the Pacific Salmon Treaty. Perhaps failed management, diseases, commercial overfishing or climate change are to blame for this loss; one can only hope that the children I saw playing in the village will learn one day to maintain the skills and traditions of salmon fishing and that the people’s respect for nature will not be reduced to stories told by the elderly.

California Small Boat Fishery

As I worked on salmon recovery projects in California, I learned a great deal about the conflicts surrounding the diminishing salmon populations. Though many issues have centered on the question of water use, the survival of salmon in California is not only an economic question, but also a question of how we value social and cultural diversity in our society.

During my trip to California, I interviewed several fishermen and women about their lives, what salmon meant to them, and how they saw their future and the future of their communities. One of the fishing boats I visited was run by Larry Collins and his wife, who operate out of Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. They had fished together for more than 25 years and were on their third boat. As Collins told me, the salmon fishing was their bread and butter, making up 70 percent of their income.

These men and women live lives of both community and solitude. When out fishing, social interaction is limited to the crew and to communication between ships. But salmon fishing is also a tightly knit community of people and families that know each other well. When the fishing season arrives, they rig up their boats and set out on a journey along the coast, a journey that can last for weeks or months. As another fisherman on the wharf, John, told me, salmon fishing is one of those careers in which each person works as part of a community. Fishermen depend on each other to know locations of salmon, to exchange information and to maintain boats. When the boats gather together to seek harbor to sell their catch, docking on the Monterrey Bay or other nearby harbors before setting out again, fishermen meet other at the docks, have dinner and a few beers, share stories, exchange information. If help was needed – for instance, a boat repair – a helping hand was always available.

They don’t have much hope, however, for the future of this way of living. With diminishing stocks and the temporary closure of the fishery in 2008, fewer young people have been recruited to the commercial, small-boat fishing industry; the lifestyle and economic incentives just aren’t enough to entice new interest.

Changes to the Sacramento and San Joaquin river deltas have played a crucial role in declining salmon populations and the ensuing conflicts. Operations of the Federal Central Valley Project and the State Water Project divert river water to irrigate a multi-million-dollar agriculture industry in the arid San Joaquin Valley and to quench the thirst of 22 million people in sprawling Los Angeles. The pumps are so forceful that their operation reverses the flow of water, causing the river to flow upstream. Consequently, large numbers of juvenile salmon are lost as they get sucked up by the pumps during their migration to the sea.

These water projects have taken the brunt of the blame for the loss of the California salmon. As a consequence, the fishing community, together with environmental organizations, has taken the fight to those that operate these facilities – the federal and state governments and the many water contractors that control water distribution. The conflict has stirred animosity between coastal and inland communities and costs the public millions as the government remains stuck in perpetual litigation.

Consideration for cultural and social linkages to natural resources such as salmon go beyond contemporary economic concerns, though such concerns should be taken into account when evaluating consequences and costs of economic and social development. Breaking these linkages creates social insecurity, instability and conflict. If this applies to modern cultures in California, it could not be more relevant than in other societies that have even closer ties to their resources.

The next stop on The Great Salmon Tour was Bosnia-Herzegovina, where I met with the Balkan Trout Restoration Group. For a biologist, the unique diversity of Balkan trout species is exciting: it includes issues such as adaptive radiation, speciation, evolution of life histories, and so on – the whole repertoire of evolutionary biology.

The endemic trout of the Balkans are all threatened by the destruction of habitat, dams that inundate ecosystems and prevent migration, hybridization with stocked brown trout, and competition with introduced non-native rainbow trout. Some of the few remaining, genetically-pure native populations are found in the Neretva River. The Balkan Trout Restoration Group is studying the taxonomy of the endemic Neretva River trout to help conserve their true native forms. I contacted the group to learn more about trout in the area, and they took me to their research hatchery above the city of Mostar.

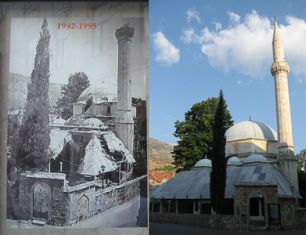

After touring the facilities, I was taken to meet a local entrepreneur. This area was the site of fierce fighting during the Yugoslavian wars between Bosnians, Croats and Serbs in the 1990s. During the battles, the entrepreneur’s house and property were destroyed. Left with nothing, he decided to start a new life by farming trout. Behind the house, he had made several smaller raceways containing rainbow trout, brown trout and brook trout that were raised to pan-sized fish. These fish were served at the house, which functioned as a bed and breakfast, and were sold locally.

The next day I visited Norfish, a Norwegian-owned fish farm that raises rainbow trout from eggs imported from the United States. The net pens, where the fish are raised, are located outside of Mostar in lakes created by local hydroelectric dams. Together, the restoration group, the local entrepreneur and the fish farm have the necessary components – research, the local interest, and the technical and economic knowhow – to create a viable enterprise.

Bosnia-Herzegovina was ravaged by war in the 90s, and the countryside still bears the physical and economic scars. Any commercial opportunity will help rebuild the economy of the Neretva River basin. As I walked around in historic Mostar to find a place to eat, I noticed that “Neretva River trout” was advertised on menus. With increasing tourism to the area, there should be a market for promoting and selling true native trout to tourists. However, the server at my restaurant did not know where the trout actually came from (other than it being “local”), but the fish in the restaurants were likely farm-raised, locally or not, rainbow trout.

People near the Neretva River do have a history of utilizing local trout. However, this connection is vanishing with the disappearance of the fish. Finding ways to (sustainably) farm and market true native trout might recreate the cultural connection to the local trout, water and land,and, in turn, this might promote a sense of cooperation among the various cultures of the still-wary Balkans. Trout do not belong to the Croats, Muslims or Serbs, but to all of them; promoting the unique Adriatic fish species might, in some small way, create a symbol around which the people, still distrustful of one another in the aftermath of the wars, can unite. Connecting the trout to the identity of the people in the area could generate demand for conserving local diversity, and a real commercial interest in true Neretva River trout may again provide an economic and political base for continued research and protection of local fish species.

The Daughters of the River God – Faith and Conservation

Mongolian rivers hide what for avid anglers may be the ultimate fishing experience – a gigantic, almost mythological trout called taimen. The taimen belongs to the genus Hucho (H. taimen) and is found in rivers in Mongolia and Siberia. Instead of migrating to the sea, this fish spends its whole life freshwater. Still, it reaches lengths of up to two meters, and its voracious appetite is famous: it eats rodents, ducklings, even adult water birds. This was the fish I definitely wanted to learn more about as part of my expedition. The taimen is a beautiful animal, with a dark back speckled with many small spots, with a whitish belly and reddish tail. In addition to this creature, Mongolian rivers harbor other salmonids, such as lenok trout (Brachymstax lenok), grayling and whitefish.

I had come to Mongolia to meet the local people and learn about their connection to the river, fish and faith. Through interviews with locals and monks in Mongolia, I learned that the relationship between nature and religion is a powerful one that often helps the conservation of resources. People in this area are herders and nomads, moving between summer and winter camps with their herds of cows, sheep and Kashmir goats. Mongolians are mainly Buddhists, and the Buddhist faith is sensitive to the killing of living organisms. A review of old Buddhist sutras and texts also mention fish as especially sacred, and according to TTF, the local faith is that killing of one taimen equals the suffering of 700 souls. I was told that the salmon are considered the daughters of the river god; thus, the taimen salmon is part of the spiritual beliefs, traditions and faith of the Mongolian herders.

During the Soviet era, however, Russians actively persecuted Buddhist leaders and destroyed most monasteries and temples in Mongolia. TTS helped the Hovsgol community to build a new local monastery and sponsored the temple’s new monk to go to the United States to learn about concepts behind conservation. By connecting faith and conservation and providing a center for people to practice their faith, TTS hopes to inform, teach and create awareness about river conservation among local herders.

But, as Betsy Quammen, the founder of TTF, eloquently put it, "a community without revenue cannot afford to conserve nature." While I was there, TTF was organizing a sewing class at the monastery: A professional designer helped transform traditional designs into fittings that would appeal to Western tastes. They hoped to sell these hand-made products as souvenirs to Western anglers at the fishing camps. The buying power of tourists will feed into local communities and provide an alternative income. However, how appealing these crafts will be to visitors and how long communities and organizations can support the work remains to be seen.

Next Step for The Great Salmon Tour

Though the concept of biodiversity and ecosystem preservation has found its way into mainstream media and public awareness, it continues to be an abstract concept for many. The Great Salmon Tour shows that as the planet loses biodiversity, we as humans lose some of our own cultural heritage – and not in an abstract way. In few other species is this more evident than in species of salmon. Salmon and trout are familiar fish on the dining table and have fascinated generations of fishermen, both recreational and professional, for centuries. Still, people know very little about the diversity of salmonid species and the place of salmon in the cultural diversity of our own species.

Here at The Great Salmon Tour, we will continue to explore the diversity of both fish and the people who rely on them – one way or another – to survive. A new set of explorations, which will cover new species and cultures, are in the pipeline, including a project that will explore the culture of anglers, from ordinary sportsmen to CEOs of large companies, politicians and celebrities. Recreational fishing is as important to these people culturally and socially as is subsistence fishing for tribes in the Pacific Northwest. In addition, we hope to head to the autonomous community of Asturias in Spain to document the old traditional family system of rivers sharing and fishing. We also hope to visit the whitefish omul in lake Baikal, Russia; the lost Conchos trout of the Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico and the scientists that found it; and the Canadian Inuit that supplement their seal-based diet with Arctic charr.

With more than 200 species and a wide variety of life histories, the family salmonidae, in many ways so familiar, provides an important way for people to learn about and understand biological diversity. Perhaps more important, however, is that these species demonstrate how biological diversity affects not only the security of our food supply, but also the connection we have with natural resources socially, spiritually and culturally. When a natural resource disappears, the relationship between people and the environment is broken, along with a social and spiritual network that is built around that relationship. Protecting species and maintaining biological diversity are not only important to social stability and security of local communities, but also to cultures and traditions that help preserve these fragile species.

Photos are copyright protected and may not be used without permission. All photos are courtesy of Peter Johnsen.