As I write this, I just learned about the horror of 87 elephants slaughtered for their ivory in Botswana in early September.

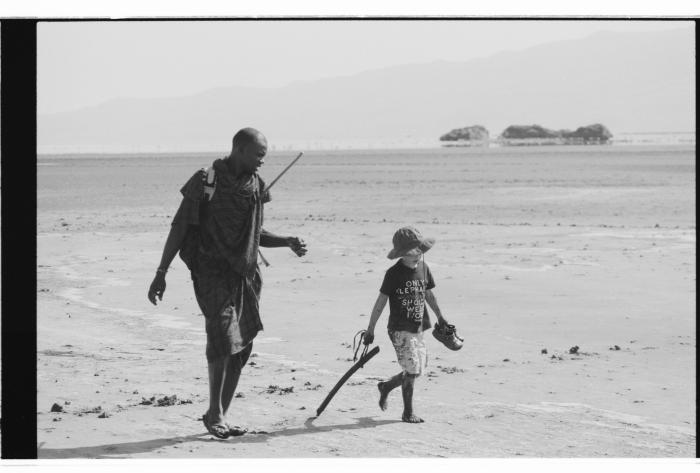

There are many ways to mourn. Through silence, rage, celebration. The newly released documentary film “Walking Thunder: Ode to the African Elephant” by Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson could not be more timely. It takes us on a very personal journey through their beloved Africa, grieving the loss of so many elephants and taking joy in the ones that, however briefly, remain. Who better to narrate the film than their son, Lysander, who tells us, “My first steps, my first words were all made in Africa. It’s part of who I am.” The film was compiled over several years and we see the boy grow in his understanding of what is happening to the great creatures of Africa that he loves. He knows what’s at stake and the price we will all have to pay: the terrible loneliness of a world without elephants.

“Walking Thunder” is lyrical, and simply gorgeous to watch. The savanna comes alive from dawn to night, and instead of wishing we were there, we feel as though we are. Staring into the dark, intelligent eyes of an elephant, sharing Lysander’s laughter at the lions napping in acacia trees, almost being knocked out of a river boat next to a giant crocodile. As the film lingers on the elephants, they are frozen in time with black and white photographs. Here shadow and light make these critically endangered animals immortal. The “Walking Thunder” of the title comes from an incredible scene where a storm moves across the night horizon, its fierce lightning illuminating the silhouettes of the elephants. Even Earth and sky seem to celebrate the mythical power of these great beasts walking the land where they belong.

Christo and Wilkinson, and later with Lysander, traveled through East Africa, visiting the Rift Valley and more remote areas of Kenya; the Selous Game Reserve and Ruaha National Park of Tanzania; and the huge wild region of Damaraland in Namibia. They were invited into the lives of local people they met, recording their stories and listening to their concerns about the changing landscape of their world. The black and white photos from these encounters are deeply intimate, the souls of the people and places offered through their eyes.

The filmmakers are told, over and over by different tribes, that the animals, especially the elephants, are kin. A Maasai tracker explains that the elephant is like a member of their family. The Samburu believe that “there is a seed of human inside each elephant.” With contemporary wit, a group of elder Namibian women agree that “the elephant is our television” as they take turns with their goats at the same watering hole as these giants.

Some of the stories in the film are told through animated line drawings, etching them into the mind as archetypal renderings, the modern equivalent of ancient painted figures and animals fading from stone. The musical score throughout “Walking Thunder” drifts behind the changing visuals like the wind, softly pronouncing each echo of melancholy and wonder that is Africa.

The local people are keenly aware that so much is being lost to them: the animals, their traditional way of life, the rain so vital to their survival. In Kenya, sitting around a hub of fire keeping out the night, a Maasai man says, “God and rain have the same name.” The rain has disappeared, and much of Africa struggles with severe drought and increasing population in a contest for diminishing resources. A Samburu of the Lenges clan explains that, in the past, the elephants led them to peace and prosperity. Now the elephants are gone, they ran away from the onslaught of armed raiders known as shifta, punishing drought, and ever-increasing agricultural and housing development. “What can the Samburu do?” Cyril asks. The man’s reply? “We pray.”

“When I look into an elephant’s eyes, I wonder about all the things he has seen,” Lysander shares. “The world needs its elephants and so do we.” Paralleling the innocence of children with the rapacious killing of elephants leaves its intended scar, though the film only shows photos of the murdered animals twice. A third image is of young Lysander, filling in the lines of a dead elephant in his coloring book.

Christo and Wilkinson wisely stay in the background for most of the film, letting their son, the people of the land, and the animals themselves tell their story. Poaching and trophy hunting are just words until the family comes across an agitated herd of elephants. Some of them trumpet and mock-charge the vehicle, their anguish apparent. Gone are the gentle animals foraging peacefully. The camera captures their fear: did they sense a poacher nearby?

Although great efforts have been made to stop the ivory trade, legal prohibitions are meaningless without enforcement. Ninety percent of the ivory sold is through an international black market. In January 2018, China banned the sale of ivory, but the slaughter continues. In Europe until very recently, antique ivory from pre-1947 was still allowed to be sold. Carbon dating of a random sample of those “antiques” showed at least half came from animals who were killed in the past ten years.

The elephants are shot, poisoned, some still alive as their tusks are ripped from the bone just underneath the eye socket. Poverty makes the elephant a target: one pair of tusks brings more than a month’s wages. The poachers are clever, hiding in the bush away from ranger patrols, perhaps even warned by corrupt officials profiting from the trade. A ranger in Selous emotionally affirms that it’s his spiritual duty to protect all the animals. “It has a right of living!” Even the radio collaring of elephants in Tanzania in an attempt to quickly arrest poachers isn’t working. Poachers have learned to destroy the collars, so an unmoving animal simply vanishes. An African conservationist working for Save the Elephants reports that when the rangers find a carcass, they put a green bough from a tree among the bones and say “Sleep peacefully” in respect of the life so cruelly torn away. In these stories is the beauty and power of “Walking Thunder.”

Unfathomably, up to a hundred elephants are killed each day by poachers. Lysander knows how lucky he is to have Africa and its great beasts as such an enormous part of his childhood. Toward the end of the film, an older Lysander remarks of his 12-year adventure, “If everyone could see what I’ve seen, I know things would be very different.” It’s simple, one elder says, “If the buying stops, the killing elephants stops.”

Walking Thunder: Ode to the African Elephant will be screened at the Santa Fe Independent Film Festival in New Mexico on Friday, October 19, 2018, at 6:00 p.m.