Preface

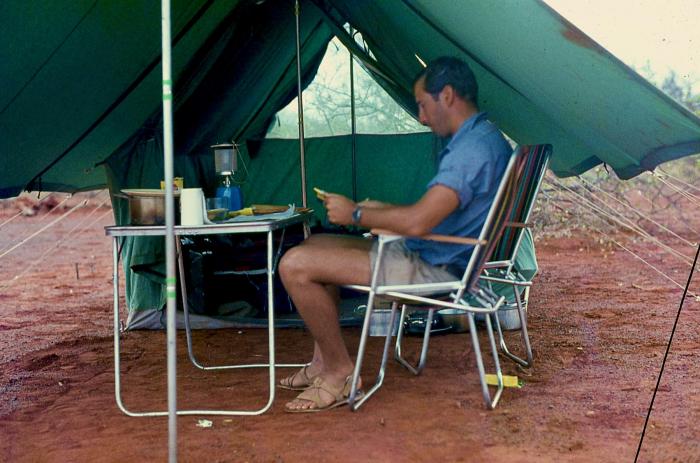

From 1968 to 1970, I was in the Peace Corps. First in Somalia and then, after a military coup there, in Kenya. The experiences I had led me to my graduate degree in agricultural economics and subsequent career in international development.

I spent over 40 years working in 25 developing countries. In the last ten years or so, I’ve worked in a volunteer capacity, specializing in microfinance in Kenya and Tanzania, which has given me the welcome opportunity to return to East Africa several times after a long absence.

While I had been contemplating writing this novel for some years, I was finally galvanized by my most recent trip to the town of Isiolo in the middle of Kenya a few years ago. The Isiolo I left in 1970 was a small town about two blocks long, with maybe a thousand people. Back then, the road ended at a police barricade at the north end of town as travel farther north required a permit. There was no electricity, just a gas station, a few dry goods stores and a bar or two. People lived off the local produce.

Imagine my surprise at the Isiolo of today, with a population of over 80,000 and an international airport. It has been designated as a planned “Resort City” by the Kenyan government — complete with game parks, conservation areas and a planned dam on the Waso Ngiro River for aquatic recreation.

These changes are dramatic and little of the old ways I remember remains. Certainly very little is written about the Northeastern Province (NEP) of 50 years ago from the perspective that I wanted to detail: the people, the land, the wildlife and the challenge of living in a harsh landscape where each day is a lesson in survival. I particularly wanted to offer a historical perspective of events that have otherwise gone undocumented. For instance, no written evidence exists of the epic purchase of 36,000 head of cattle and the trekking of them over 400 miles north — the centerpiece of this novel.

I decided to write in the third person and created the character of the narrator, Wade Stiles, which allowed me the freedom of a novel as opposed to the confines of a memoir. However, everything in this novel actually took place, with the narrative helped along with a little literary license, particularly for the dialogue. While I invented numerous names, the people in the novel depict actual personages, and I kept Hector Douglas as himself because I wanted to acknowledge both his importance in the history of the NEP and what an extraordinary person he was.

I learned Somali from being immersed in the culture. There were no language books back then and the spelling used throughout is my own phonetic transliteration. My Swahili is likewise self-taught and was the lingua franca used throughout the NEP at that time. I was delighted when, on a recent trip to Zanzibar, some people told me that I speak Swahili like their grandparents.

Excerpt from Sunset in Wajir

They had continued with the cattle markets all the way up to Mandera — on the Somali, Kenya and Ethiopia borders — purchasing unexpectedly large amounts at each cattle market.

Finally Hector said, “By my reckoning we have purchased over 36,000 head, and that’s it. No more. I don’t care how many are brought to market and from where. This is sheer madness and we are going to pay a terrible price trying to route all these animals to proper water and grazing. Reports are that we are already losing animals in alarming numbers along the way, and now we have another 6,000 head at this market to march over already overgrazed areas.

“Moghul, I want you to leave tomorrow morning and establish water sites from here to Tarbaj. Wade, you are responsible from Tarbaj south. You both can link up at Modo Gashe and trek to Garsen and then on to Lamu. I will leave for Nairobi in the morning and be in contact by wireless every morning at the usual time. Any questions?”

“Sure, lots,” began Wade.

“Don’t ask,” snapped Hector, “because I haven’t any answers. Now if you would be so kind as to pass that bottle, maybe I can forget this balls-up for a few moments.”

The first water site Wade established was at Tarbaj. He wondered how the place got its name because there was nothing there, just acacia bush with a red sand road running past a nondescript point in the road. Nonetheless it was determined that a 40,000-gallon water tank was to be placed here and filled from the wells at Wajir. The ground was cleared and leveled, and a butylene liner was draped over a frame of heavy wire, buttressed with support poles. The lorries worked nonstop for three days until the tank was over half filled and the first mob of 2,000 cows, which had been held off in the bush, was finally allowed to break loose and drink at the four water troughs filled from two-inch syphon tubes running from the tank.

However, just before the cows started to drink, a peculiar buzzing filled the air and grew louder until a thick black cloud hovered over the water and a yell broke out from the herders, “Shinnida delaga — killer bees! Socod — run!”

Wade barely made it to his tent while others ran into the bush. A few who were not so lucky were swarmed and one leapt into the tank and was stung mercilessly on his back and the top of his head. The bees swarmed all that day and through the night, and were finally satiated the next morning.

It was only after they were gone that Wade dared to unzip his tent and venture forth, completely exhausted from over fifteen hours in 100-degree heat in the tent with only one water bottle. He immediately dove into the tank along with several Somalis and stayed there until his body temperature lowered and the danger of heat prostration lessened.

It was to be his first, but certainly not his last, lesson on the consequences of environmental alteration. He had created an artificial environment in a semi-arid land that attracted first bees, then, in sequential order, numerous birds, an itinerant elephant and a dozen hyenas — all drinking their fill before it was safe to water the cattle. African killer bees, when agitated, would swarm anything in their path from the thickest hides to the frailest newborn and anything in between. They were considered to be among the most dangerous of African species, outclassed only by hippos and snakes. And that day Wade was to learn a hard lesson, one not in his development handbook, one learned only from experience, to be added to his lengthening list of bush survival tips. By the end of one year in the bush he was to become a tried-and-true master of hard living. But until that time he muddled through and adapted to the challenges thrown at him.

Shortly after the bees left, an elephant arrived. They tried to shoo it off by banging pots and shouting but the cattle, now driven mad with thirst, broke away from the herdsmen and rushed the water troughs. They literally pushed the elephant out of their way. Luckily none were trampled, although several were butted into the water troughs and floundered until the troughs were upset, spilling water onto the red sand.

The next mob of 2,000 bolted from their herdsmen and rushed the now-empty troughs, slipping in the wet sand, throwing their heads about with crazed eyes. Another mob broke loose and now 6,000 head of frenzied cattle attacked the only remaining source of water — the tank. Some climbed over the backs of others and ended up scaling the tank walls and flopping into the water. Others pushed on the sides until the walls caved and water over-topped and began to flow from breaches. Several thousand gallons cascaded onto the sand while herdsmen brandished sticks, twisted tails, kicked and tugged to try and instill some order, to no avail. Now the elephant, who hadn’t seen this much water in months, waded in and with a series of shrill screams laid into the cattle with his trunk and lashed a few out of his way until he crashed through and belly flopped into the remaining pool.

Wade had climbed up on the bonnet of his vehicle for safety and from this vantage watched the unfolding scene in fascination. He had never seen anything like it and was utterly without any idea of what to do other than observe. The Somalis had backed off, wisely not wanting to get trampled, and ran over to stand by the Land Rover, apparently awaiting some instruction from Wade.

The elephant now started to stand but slipped in the wet membrane of the tank and fell headfirst, landing with a splat and then looking around stupidly with a face plastered with red mud. First one Somali began to laugh, then the next and finally all were convulsing with hysteria. Wade took a little longer but joined in, realizing there was simply nothing else to do. There they were, with a busted water tank, 6,000 thirsty cattle and an old tired elephant in the middle of nowhere. What else was there to do but laugh or cry? They chose laughter.

Author’s Notes

This excerpt from my novel Sunset in Wajir illustrates the unexpected consequences of introducing a modification to an environment, in this case a large water tank in a semi-arid landscape during the dry season. The purpose was to water cattle being trekked from long distances. The unintended result was providing a water source for a myriad of fauna, from insects to herbivores and carnivores. What was really amazing was how the water was sourced and how information about it was transmitted among species. First came the insects, then the birds and finally the larger mammals, all seemingly following some sort of signal in succession.

Environments tend toward equilibrium — never actually achieving it, but in constant flux, pulsing around a center of stability, weaving a pattern of moderation juxtaposed to spikes of extremes. The pastoralists found in the Northeastern Province of Kenya lived in a quasi-symbiotic relationship with the environment. Their herds were adapted to either grazing or fodder, and their numbers were kept in check by the available vegetation and water. These resources were shared fairly equitably with native animal species and other pastoralists (although range wars were frequent).

In 1970, the Kenyan Government decided to purchase cattle throughout the Northeastern Province through the Livestock Marketing Division of the Ministry of Agriculture. A staggering 36,000 head of cattle were purchased and trekked over 400 miles through a semi-arid region with few water resources and scarce vegetation. Nothing of this magnitude had previously been seen or even planned. Temporary water sites were erected at strategic locations and ad hoc stock routes meandered into traditional tribal rangelands.

The end results could be evaluated using a short-term view or by taking a broader, long-term perspective. In the short term, money was injected into the area and cattle were removed, changing the cultural perception of wealth. Fragile rangelands were instantly depleted, causing other species to migrate due to habitat loss. Most of the long-term effects were less noticeable, but one blatant indication was the proliferation of less desirable vegetative species, a trend toward forbs and away from grasses. This ultimately changed the composition of local herds, moving away from cattle and toward goats and camels, although this shift was already in progress as a result of the increase in the human population and drought conditions.

Takeaway

Biodiversity includes a combination of human, vegetative and animal interactions. The fragility of this system only becomes apparent when there is a disruption. When one of these factors — or all, or a combination — predominates over another, there will be upheaval. Whether the impacts are anticipated, wanted or contrary is a matter of conjecture. Since humans are the dominant species, at least in our own minds, all values are measured from our perspective. Unfortunately, we have normalized expediency as a value, cloaking it in the guise of progress and measuring it throughout our systems of politics and profit.

In the case of this purchase of a huge number of cattle that were then moved overland through a relatively closed ecosystem, there were obviously going to be immediate effects. What was not so obvious or immediately visible were the long-term and lingering impacts — a powerful lesson about the fragility of biodiversity. Actions have consequences.

All photos courtesy of Jack Meyers