Looking through the truck window into a vivid cold winter scene in the subarctic forest of the 1970s Yukon Territory, I was struck by the temerity of the animals that lived and even thrived in such an extreme yet beautiful land. I myself was one of those living in this arctic landscape, although I was safe in a warm vehicle while it was 20 below outside.

As we passed through a broad valley, my father announced that he would pull over up ahead. We got out of the truck by the side of the road and stood in the snow. My father held out his arm and made a kissing sound with his mouth, telling me to watch the line of trees at the edge of a clearing. As I looked and wondered what was happening, a gray and black blur flew out of the dark spruce forest, calling out a similar sound to the lip squeaks my pa was making. With a flourish of feathers and flaps, a darling and wonderfully clever wecasejac, or Canada gray jay, landed on pa’s outstretched hand and looked at us with keen interest. I was delighted, astonished and curious as my pa pulled a few crumbs of food from his pocket and fed the jay, who joyfully gobbled down the morsels while standing comfortably on my father’s hand. The bird was not at all bothered by the two humans staring at him and talking in soft voices, trying to engage the wecasejac. After a time, the bird hopped off, bounced around for a bit on the ground, inspected the truck, came back to pa, looked at me and then flew off into the cold dimming winter day. I have since had many encounters with those lovely, cheeky birds, as I am sure many other outdoor enthusiasts have. They have been nicknamed — rather ungraciously — “camp robbers” as they often seek food at campsites.

Gray Jay /wecasejac/ Perisoreus canadensis

That experience came at an age when many lessons about our other relatives on this planet began to solidify into an understanding of my place in the web of life and creation. Raised in the northern wilderness, humans were greatly outnumbered by the diverse abundance of animals, trees, plants, aquatic life and insects — oh, the insects! We depended on this diversity for our sustenance and our spiritual nourishment. When patient and calm enough, we could develop a companionable tolerance or even friendship with members of our nonhuman family. Each creature had a place at the table in the seasonal turn of abundance and scarcity. With teachings, stories and adventurous exploration, I became aware of a language that could cross the barrier between humans and other species — whom I often refer to as “people.” These friendships and the diverse cultures of nonhuman people are invaluable tools for understanding and alliance, helping us to feel a part of a greater family.

Because of that early meeting with one of the wild ones, and many others since then, I began a lifelong quest to kindle the flame of relationships with our relatives. I would like to share one of these stories with you, in the hopes of kindling that flame in your life — to reach out and connect with the community of life that includes our greatest teachers, allies, friends and cohabitants on this good earth.

One of the cutest critters in the far north has to be Urocitellus parryii, the Arctic ground squirrel, or sik sik, also known colloquially — and erroneously —as a “gopher.” Gregarious, industrious and loving family members within their communities, they seem to me the closest to human societies in many respects. I even became friends, and eventually lived, with these delightful rascals (I’ll share more about that story later!).

Arctic ground squirrel Urocitellus parryii

The sik sik is possibly the most predated mammal species in the north. Every predator, from ermines to humans to grizzlies, depends on them for meals to some degree. Yet they have a robust population and their conservation status is “secure.” They live in large burrows with apartments connected by tunnels, spend the summer as diurnal foragers and hibernate for the winter months. Extraordinarily, their brain temperature drops to just above freezing during hibernation while their core body temperature goes down to -2.9°C/26°F. During this time, their heart rate also drops to one beat per minute and their blood temperature falls below zero. An amazing process! Female Arctic ground squirrels hibernate longer than the males. The females overwinter from August to late April and the males from late September to early April.

Growing up in the Yukon River valley, sik siks were plentiful, and encounters with them were frequent and interesting. I remember the many times I sat calmly on a riverbank, observing them play, forage and socialize. I especially enjoyed watching the young ones’ antics while the rest of the community was busy with life.

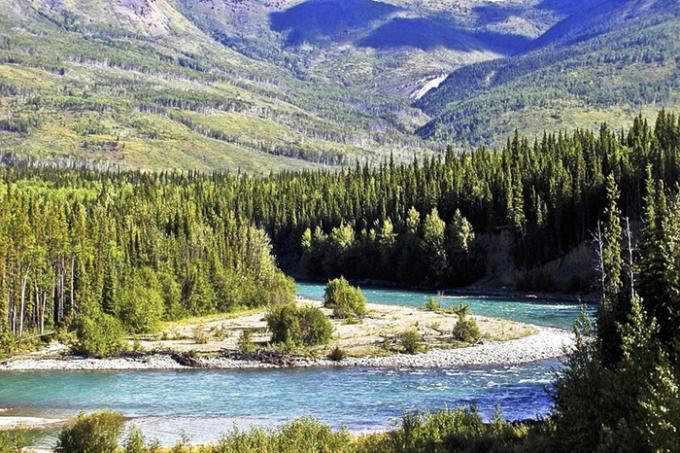

As a young man years later, I spent time living in a cabin on a bluff overlooking the incredible Takhini River valley, many miles from civilization. I was staying there to feel closer to the natural world, work on my music composition, hike and forage. While I was welcoming to visitors who made the long trek to get there, I was blessed with two extra-special visitors that spring.

Before I get into that tale, allow me to share a little about how I had learned to create opportunities for animal relationships and the language that facilitates them. My bush education was steeped in both the settler ways of living on the land and the indigenous ways of living with the land. I received indigenous teachings in various ways, primarily through my father, his work and the people he worked with. On my father’s side we are Otipemisiwak, or Métis, an indigenous group in Canada. He became a conservation officer for the Yukon Territorial government when I was young, and his work often involved local First Peoples communities. It was from them he acquired the very simple instructions so deeply held in Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), which are to be grateful, to practice reverence for community and creation, to enjoy life, and to protect and steward life for the next seven generations. I then received these teachings in kind. I was raised in a place where settlers occupied the wilderness in earnest starting in 1945, with the building of a wartime effort highway. TEK was still practiced and taught within First Peoples communities, even while the settler government policies tried to destroy it.

The settler way was one of dominance, resource exploitation and scientific reductionism, which basically views the land as a “thing” to be lived on. Water, plants and animals are considered resources to use and abuse. Animals were also seen as “things,” and either a threat or a meal. The pioneers and descendants of the settlers had a grudging respect for the animals and the land, but it was not heartfelt, it was adversarial. The earth was never an ally, only an opportunity. This way has led to great technical achievement — and blinding arrogance. I was taught scientific thought within this context, which helped me adjust to the beliefs and methods of the dominant culture. Yet it still denied the connection to all things that I felt. My father worked with the Ministry of Natural Resources, which concerned itself with tallying numbers, making observations and “managing” the land with scientific method, ostensibly denying the TEK of the First Peoples until only just recently.

Through these diverse teachings, I became both a scientist/naturalist and a keen observer of how our relatives behave as beings in their own right, within their species and without. In my observations of animals, it seemed that “ignoring is the best policy” during interactions unless hunger, personal space or a territorial dispute is the foremost concern. Otherwise, most animals will maintain awareness of the other, but with an affected diffidence, as if nothing is out of place. This “ignoring” principle essentially means not paying attention to the encounter but sharing space and, naturally, resources. Each animal has a very predictable set of rules of engagement and a language they use to communicate their intentions to each other and between species. My father always told me that animals are very predictable once you learn these rules and languages, and that the only truly unpredictable animals are humans. Interspecies friendships can develop, given plentiful resources, some time and interpersonal habituation.

With all that in mind, let me get back to the story.

I had set myself a routine at that tiny cabin perched above the clay cliffs of the riverbank. It involved an early morning hike and forage, gathering water from a spring for use at the cabin and collecting firewood. I would then return to the cabin, make notes and observations about the weather and the wildlife I’d seen, and then do some cleaning and preparation for meals. That was my day-to-day existence in the bush.

Spring, summer and fall in the Yukon are one great rushing sun-washed blur, with only three months of relatively snow- and frost-free days; all creatures of the north tend to have endless chores to do in a very short span of time. Perhaps because of this, and the endless sunlight, visible activity from my new neighbors increased daily and, because I was not deemed a threat, they began to relax around me while they foraged, groomed and generally kept busy. There were two of them, a mated pair, and they knew my daily routine. That routine and my ignoring them gave us an amazing chance to build a relationship that would bring me great joy — and bring them some comfort and safety. I observed the pair with sidelong glances, and took notes in the evening about their activity — how they were taking in food and putting on weight, and the distinctions that allowed me to tell them apart. I named them Reb and Flo. They had shown me some of their personalities, and the names seemed to suit them. After three weeks of getting to know each other, something lovely happened.

I returned from a successful foraging and sat down on the deck with a cup of tea to enjoy the visual feast that is the Takhini River valley. I was sorting through the spruce roots I had gathered that day in the warm spring evening. I had been bent over my sorting, so I straightened up my back, reached for my cup of tea and was startled to see Reb sitting not two feet away from me! He looked at me, I looked at him and then, using the ignoring principle, I turned away to take in the view again while keeping him in my peripheral vision. He did the same, sitting there calmly, looking out over the vast northern landscape. I was thrilled and comforted at the same time. I had made a friend. That first visit lasted about an hour, with Reb sitting serenely and occasionally grooming, and I sorting the roots, drinking tea and humming tunes under my breath. I went to bed with a fine glow in my heart that night.

And so it went for the next week. Every evening, Reb and I would sit and enjoy the view in companionable silence. Flo would eventually get up the courage to join us, but she was always the busier of the two in the evenings, bustling around in their home, setting stores perhaps, or expanding a room or tunnel. I would also see them coming and going throughout the day, taking care of their lives like I did, and I began to pay attention to how they communicated with each other. The sik sik are so named for the sounds they make when a threat is perceived, but they also use many other sounds. I tried to note them, when they were used, for what and how often. I began to recognize some of these sounds in other sik sik communities I passed while foraging away from the cabin. I learned to use their warning sounds to be on the lookout for predators close by — they once even saved me from a possibly awkward meeting with a black bear! Reb and Flo were not only my companions but also my teachers.

One day I forgot to close the screen door when I went out to collect water from the spring. Upon returning to the cabin, I caught those two rascals raiding my couch for stuffing! What a scene, me at the door with a heavy jug of water in my hands, mouth agape, and Reb and Flo frozen on the cushion of my couch, mouths stuffed with foam. I asked aloud, “What are you two doing?” They looked at each other, looked at me and then took off like shots between my legs, across the deck and into their hole. Ha! I laughed and laughed — what a wonderful robbery it had been. Later that evening, as if nothing had happened, Reb and I were on the deck, me with my tea and he with a happier mate for the insulation they had gained for the little ones on the way.

I left the door open for the next few days in the hopes that they would feel welcome to come and pilfer what they needed. But the mosquitoes were getting bad, so I closed the door and cut a small flap in the screen door, wondering if they might figure it out. And figure it out they did. One night, fast asleep in my bed, I was startled awake by clanging and banging in the kitchen. I grabbed the rifle by the bed (this is the wilderness, and bears are a real and relatively common intruder) and burst into the kitchen, only to find Reb and Flo rummaging through my cupboard of pots. This time, however, they did not scamper away. Instead, they just looked at me and casually walked out through the flap in the screen without a care in the world.

This continued for the rest of the spring and summer — they helped themselves to anything they needed, and I tolerated the midnight raids. And every day at tea time, the two or three of us would relax on the deck in each other’s company. I knew their children had been born, but I did not see them until toward the end of summer. Even though it was only when they thought I wasn’t nearby, it was a tremendous experience to see them flourish and grow under the deck of that little cabin.

This was not the first time I had made friends with animals, but it was poignant and distinct. It was a sharing of space, my human space with their homestead, and it will remain a very fine example of how closely I could share time and space with the wild ones. Friendships with animals require an openness of heart and mind, and patience over months and possibly years, especially as food was not used as the medium of trust. Food can be a useful to create interactions with animals, but it is not the best tool. It doesn’t allow for a genuine exchange and can sometimes lead to dependence on learned behaviors that do no benefit either of the species involved. Using the ignoring principle, tolerance and an open heart will win over almost any being, given time and care. For countless millennia, humans were — and in some places continue to be — a part of a community of life. Like any community, all its denizens have their own personalities, likes, fears and families living in coexistence. There are tensions from subsistence, but partnerships, alliances and even friendships are also in abundance. If we take the time to look, listen and encourage communication between ourselves and the other animals we share the planet with, we will be enormously enriched by it.

Autumn was drawing near and it was a particularly warm day on the high bluff. As always, I had my cup of tea and was taking in the view of the vast and gorgeous wilderness around me. Without warning, Reb clambered up onto the bench seat beside me, looked me right in the eye and then gently climbed up on my leg. He stretched out full length on my knee, sighed and fell asleep. With joy and wonder, my heart filled up with the friendship I had been given, without strings or rewards offered.

I saw my two friends in the days leading up to the great cold, busy with fattening up and raising their kids. Once the heavy frosts came, I never saw them again and my time at the cabin was up. I returned the next mid-summer and it seemed they had moved on, but those sik siks will always live on in my mind as the furry housemates who captured my heart and gave me so much for so little in return.