Find a bug (and draw it). Find plants that are ingredients in pizza sauce; in toothpaste; in salsa. Find two living and two nonliving things.

These simple prompts are given, not necessarily because of their academic rigor, but to spark curiosity in elementary schoolers as they tour their school's garden in the summer heat.

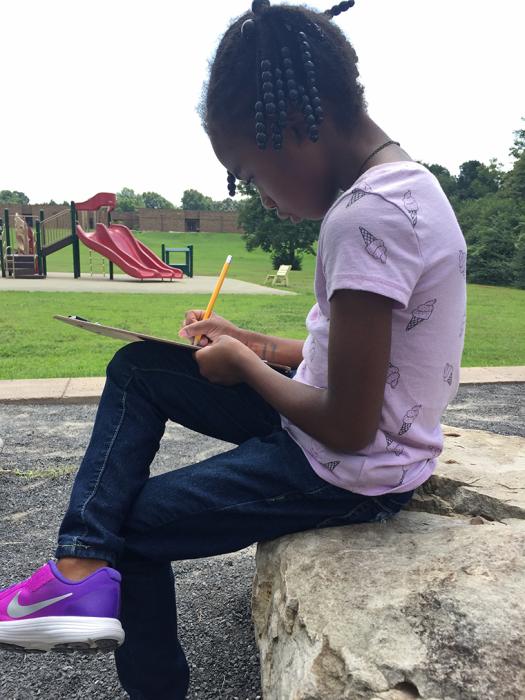

It feels like 105ºF, but the kids are outside anyway, propping clipboards on their hips, bending close to plants, and brushing their hands over leaves and stems. As they move from bed to bed, they draw pictures or write down what they find to complete their scavenger hunt, including something smooth, a plant with two colors and something bigger than your hand.

A pair of students in second grade walk up to the tomato vines climbing a wire trellis. One turns to the other as she touches the fruit hanging on the vine and asks, "What is this?" Her partner replies confidently, "It's an apple!" They make moves to put pencil to paper, but I interject with a few questions of my own before they write down the wrong fruit in the “smooth” box.

The school gardening movement has been gaining traction and popularity across the country. The Kitchen Community, a national nonprofit organization with a regional office in Memphis, has built over 400 school gardens across the country, and we are just one of many organizations working to bring gardens to schools. While it’s difficult to find up-to-date data on exact numbers, as of the 2012-13 school year, approximately 26 percent of public elementary schools in the U.S. had gardens, which can be used as outdoor classrooms and living laboratories to enhance learning about core subject material, or as more of an extracurricular activity that focuses on sustainability, nature or food production. No matter how the garden is used at a particular school, it allows for creative exploration that expands students' interactions with what adults love to call the "real world."

Most of what I do in the garden revolves around answering questions while discerning what students are pointing at. What kind of plant is this? (Hopefully they're not pointing at a weed I don’t recognize.) Why is this dead? (It's usually not. Or, it’s a great opportunity to discuss plant needs.) Is this a daisy? (Almost every flower is at some point mistaken for a daisy.) What is a boulder? (A really big rock — we use them as seating in our gardens.) What are these white rocks in the soil? (Perlite, which is a type of volcanic glass that helps soil to retain water. There are always a few students who jump back thinking that the association with volcanoes means "lava.")

The rest of what I do is turn around and ask the students questions. What do plants need to grow? What part of a plant soaks up the water? Are bugs good for the garden? What is an example of a pollinator? What will happen if we pick a tomato too early? What will happen if we break the stem of the plant? Do you like spicy food? Have you eaten mustard greens before? What is your favorite fruit or vegetable?

The reality is that many adults don’t know the specifics of where their food comes from or how they grow, so it’s no surprise that students don’t either. This becomes even more apparent when we begin to ask them questions about their food, which often leads to amusing answers that are also good conversation starters.

When I asked a group of kindergarteners preparing to plant lettuce seeds if they liked salad, one confidently raised her hand to say, "I like chicken salad!" Unfortunately, we were not planting chickens in the garden, but her enthusiasm for chicken salad was admirable. Chicken is a common food, and therefore a popular theme. A second grader, when the group was asked if they had grown anything before, told us that he had planted chicken nuggets — we are still unsure whether he reaped any benefit from this effort. At a different school, two girls hung back after they planted some seeds with their second grade class to ask me if we could grow bacon in the garden. I told them that bacon is a meat you get from a pig, and so you can grow pigs, but you have to be a pig farmer. The two of them looked at me with wide eyes and asked, "So you have to kill the pig?" When I confirmed that you did, one girl pushed back her shoulders and exclaimed, "I'll do it!" I'll have to touch base with her in a decade or so to see if her aspirations to pig farming came to fruition.

These stories aren’t meant to poke fun of students' lack of knowledge, but rather to shed light on the fact that sometimes, particularly for elementary school-aged children, things go over their heads. Even if students are familiar with fruits and vegetables from home or health class, knowing what produce looks like before it’s harvested or the difference between cucumber and watermelon leaves usually escapes them. What's exciting is that these questions and conversations are being started because of their school's garden.

The schools we work with in Memphis can plant whatever they want in their gardens, but each season we provide seeds and seedlings to participating schools. We make sure to grow a wide variety of fruits and vegetables to showcase the different plant parts you can eat, plant life cycles, herbs, and “themes” like a salsa or salad garden. Children are exposed to everything from root veggies such as carrots, radishes and beets; to leafy brassicas such as collard greens, kale and mustard greens; to herbs such as mint, basil and oregano; to fruits such as tomatoes, peppers and watermelons. For some of these, we plant different varieties to showcase varying tastes, colors, shapes and more — for schools that planted summer gardens this season, we gave them New Girl, Sweetie and Yellow Pear tomatoes. Students will get to see and taste the differences between the larger, red New Girl, the small, cherry-like Sweetie, and the yellow and (surprise!) pear-shaped Yellow Pear variety.

From the bees and wasps pollinating the flowers to the monarch butterflies cocooning on the milkweed and hornworms unfortunately decimating tomato plants, the garden is a haven for biodiversity. Students are exposed not only to the wide variety of edible plant species grown in the garden, but also to the broader ecosystem that thrives off these plants. By seeing how each of these intricate pieces interact to create a thriving symbiotic ecosystem in their school garden, they are able to greater appreciate biodiversity in broader contexts.

All this praise for gardens is not to say they don't come with caveats — they need to be watered, weeded and managed for pests, students have hands covered in soil, and sometimes seeds don’t germinate and you don’t know why. School gardens are not the be-all and end-all for teaching students about food, biodiversity and the living world, but they are an excellent resource to be used by teachers in tandem with classroom learning. As their time in the garden draws to a close, students may have asked more questions than they answered, and a tomato might have gotten picked too early, but the one certainty is that they’ll definitely need to wash their dirty hands when they go back inside.

Photos are owned by Erika Hansen, and cannot be reproduced or used without permission.