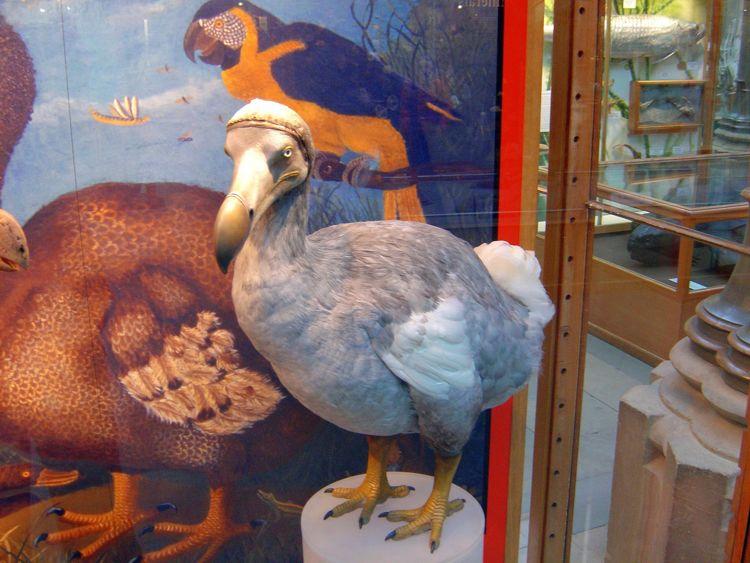

As individuals who work in the environmental field and whose hobbies involve being outdoors, we had heard of some of the extinct species featured in Brief Eulogies for Lost Animals by Daniel Hudon before we read the book. The popular metaphor-bird, the dodo, is one extinct species almost everyone knows about, and we also recognized Bachman’s warbler, the passenger pigeon and the ivory-billed woodpecker. But the vast majority of the lost animals in this book were completely unknown to us— so much so that we would pause between eulogies, twisting our imaginations to visualize Falkland Island wolves, pig-footed bandicoots and Cape Verde giant skinks.

Daniel Hudon divides his book by continent, mixing poetic descriptions with first-person accounts or lines of verse featuring the species. At the end of some descriptions, he fits the creatures’ trajectory with the overall history of human-caused extinction. For example, the Tecopa pupfish was “the first species to be removed from the [Endangered Species Act] list due to extinction,” the harelip sucker “became the first fish to be declared extinct in North America” and the Pyrenees Ibex, lost in 2000, was “the first extinction of the new millennium.” Several species were given the Latin name of extirpo for being already extinct at the time of identification.

Some of Hudon’s eulogies seem almost too brief, begging for more description of a species’ appearance or behavior, but then you must remember that this is a book of eulogies and what is known about some extinct species can barely fill a sentence. Understanding how little is known about some of the species eulogized in this book leads to wondering about those species we never knew at all, those that vanished into the darkness of extinction with never a word written about their existence.

While Brief Eulogies initially appears to be just that, some of the longer tributes paint a picture of a lost world— an otherworldly place full of abundant and diverse animal life, many of which knew no fear of humans. There are stories of birds, reptiles and amphibians living in colonies so large, they seem unfathomable. Herds of huge land turtles once roamed the island of Rodrigues and flocks of passenger pigeons a mile wide once took hours to fly overhead. This collection of eulogies conjures up a world so full of biodiversity that what we now experience seems like a mere splinter of the original vastness of life on earth. It is difficult to imagine that a species that once included billions of individuals is now gone completely because of human actions.

The human impact cannot be ignored in the fate of extinct animals. Hudon’s homages describe loss of habitat, the introduction of invasive species or extirpation through hunting— it seems that all extinctions can be linked in some way to human actions. In many cases several species were rendered extinct by one human activity, such as the birds of Guadalupe who were lost because of the introduction of goats. With others, such as the Atitlán grebe, the combined impact of pollution, invasive species and habitat loss ultimately caused their demise.

We recommend reading this book in one or two sittings, letting the species wash over you. Emotionally, moving through Brief Eulogies is both painful and awe-inspiring. While we definitely felt what Hudon described by using the Polish word “zal” — meaning “a sadness or regret, a burning heart, like a howling inside you that is so unbearable that it breaks your heart” — we were also reminded, again and again, of the wonder of nature, the seemingly magical adaptation of species, and all the miraculous flora and fauna we still have left that we must strive to protect.

Hudon’s book begins with the quote “Forgetting is another kind of extinction.” While these species are gone, we hope every ecologist, naturalist, environmentalist and student obtains a copy of Brief Eulogies for Lost Animals to prevent these species from being lost from memory forever.