Broken very much incorporates the yin and the yang, but to focus entirely on dichotomies would be to miss the point."It wasn't intentional in any conscious way," Jones said in a March 2011 interview from her home in Boulder, Colorado. "That's very similar to Stanford Addison's view of the world, which is that it's not one thing or the other; it's the balance that matters. I remember he said to me once: you can be too happy."

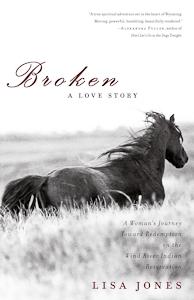

Broken is Jones' memoir, but it's far more than that. It's a portrait of Native American culture, an investigation into nature-based spirituality and a celebration of the human spirit. It's also an expertly spun biography about Addison, a quadriplegic Northern Arapahoe spiritual healer who had a gift for "gentling" wild horses.

In August 2002, Jones visited Addison to interview him for a story she would write for Smithsonian magazine. It was that initial four-day assignment that planted the seed for an eventual book and provided the central metaphor, finding your center, which became the memoir's theme.

Jones relays that this was one of the most basic of Addison's horse breaking techniques: "The only way to endure confinement is to accept it," she writes. "Stanford called it 'finding your center.'"

"Finding your center is the central metaphor of the book," Jones said. "The horse has to stop panicking. I think all those dichotomies revolve around that, that there is a center."

During the four years she captured in Broken, Jones learned how to see and, to some extent, be like Addison, who suffered his debilitating injuries in a 1978 car accident on the reservation. He was twenty.

"I had never seen bad luck heaped so hugely upon a human body," she writes of her first meeting with the man who would become a trusted and lasting teacher and friend. Despite Addison's injuries, which confine him to a wheelchair, Jones returns throughout the narrative to his accepting, perceptive eyes. "He looked at me, his gaze mild, open, alert and unblinking. It walloped me just the way beauty would."

Although it is a memoir, the theme in Broken is bigger than its author. It is about a way of seeing that pierces the shiny sheen of western living and the hardscrabble nature of reservation life alike. According to Jones, life in Western civilization is almost always driven by a desire for the pleasant and the profitable; death and suffering are tucked in the shadows. Conversely, Addison looked to life's challenges as the nature of things. "He really believed that when something great happens, something bad comes with it; something bad happens, something great comes with it," Jones said.

This contrast between life on the Wind River Reservation and modern-day Colorado, Jones' home, is stark."The negativity in their lives is so great, it's explicit, whereas in our lives it's almost implicit. Life up there is just so dramatically difficult. There is death and poverty and disease. We just don't experience it in Boulder – at all. And, yet, I felt like it was a more accurate vision. It's like what life was, full of precariousness and fragility.

"I feel very alive when I'm up there. In a way, our culture doesn't feel alive to me because we put death and suffering in the shadows." Moreover, such contrasts play out in the ways these cultures interact with the natural world. When considering some of the natural disasters that have produced widespread destruction and headlines in the past decade, Jones observed that Western culture seems out of touch and at odds with natural processes.

"It seems like we have really separated from nature. And shamanism, which is a religion that isn't separated from nature, has become a marginalized religion for disenfranchised people," she said. "We're poisoning the planet. If we make it through this, I think there's going to be a huge down-scaling in our lifestyle. If we don't include nature in our system of faith, we're going to perpetuate a cycle of abuse with the planet." And that gets back to the concepts of acceptance, centeredness, mercy and love. Under Addison's wing, Jones found these qualities among people who have suffered, and continue to suffer, more than most Westerners will ever know. Their lives, Jones points out, are post-apocalyptic, an apocalypse brought on by people upholding concepts like land ownership and nature domination over the sanctity of life.

"We have victimized and marginalized the brown people and black people and red people of this planet," Jones said. "They live a post-apocalyptic life, and yet they live, and they survive, and they keep going."

Addison died last month at the age of 52. He had spent much of the last six months in the hospital, struggling with septic bedsores and diabetes. Jones visited him as often as she could. "Losing him goes really deep, but it's a clean wound," she said. "There was nothing left to say. He knew how much I loved him."

His funeral was held at his home, the burial in the family graveyard three miles up the hill. "At the funeral I think a lot of people felt the way I did, like magnetic north had sort of disappeared. We are so used to watching him do the unthinkable, in terms of endurance or kindness. He even blew away the head of the Intensive Care department at the hospital with his ability to survive, and his life story. I feel pretty wretched right now, but behind it I'm so, so grateful that I knew him, that I got to see what was possible to do with one human life."

Photographs are copyright protected and used with permission of Lisa Jones. Photos may not be reproduced without permission. The photo of Standford Addison and Lisa Jones was taken by Nancy Carter and used with permission of Lisa Jones. Please visit Jones' website for further information and additional photographs.

1. Lisa Jones, Broken: A Love Story (New York: Scribner, 2009).