When I first started working on an article for World Pangolin Day (which takes place every third Saturday of February), I did not realize how few people even knew pangolins existed. As an evolutionary biologist, knowledge of other species is part of my job. Because of this, I’m often surprised to realize that I’m the only person in a room aware of the fact that part of the world’s diversity includes eight mammal species covered with scales.

Even my children were unaware of the pangolin – a clear deficit in my education of them. However, both were interested in learning about them. My ten-year-old daughter, Sage, got particularly fired up about pangolins – especially when she learned that all eight species are vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered due to poaching and habitat loss.

This is, of course, one of the hazards of being a parent who knows about the risks many species currently face. As I tell my kids about some amazing critter, I also have to wrestle with the obligation of telling them that that critter may not be around in fifty years.

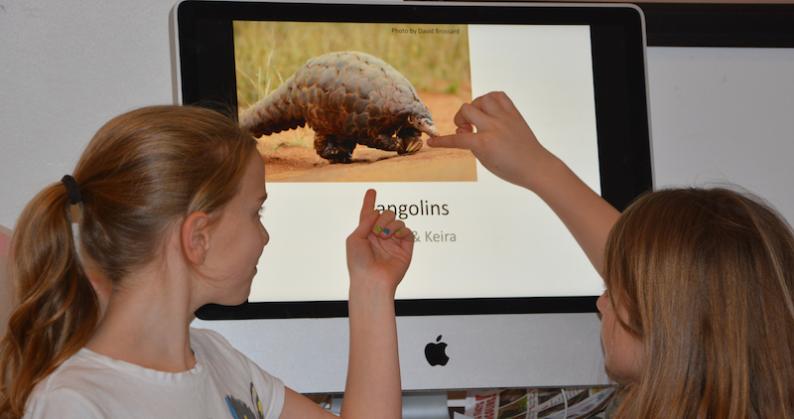

Rather than becoming overwhelmed by what she was learning, Sage wanted to do something about it. She told her friend Keira about pangolins. The two of them decided to research the animals and make a PowerPoint presentation to share with their fifth grade class. Here are some of the things they shared.

Four species of pangolins live in Africa (the tree, giant, Cape and long-tailed), and four species live in Asia (the Sunda, Philippine, Chinese and Indian).

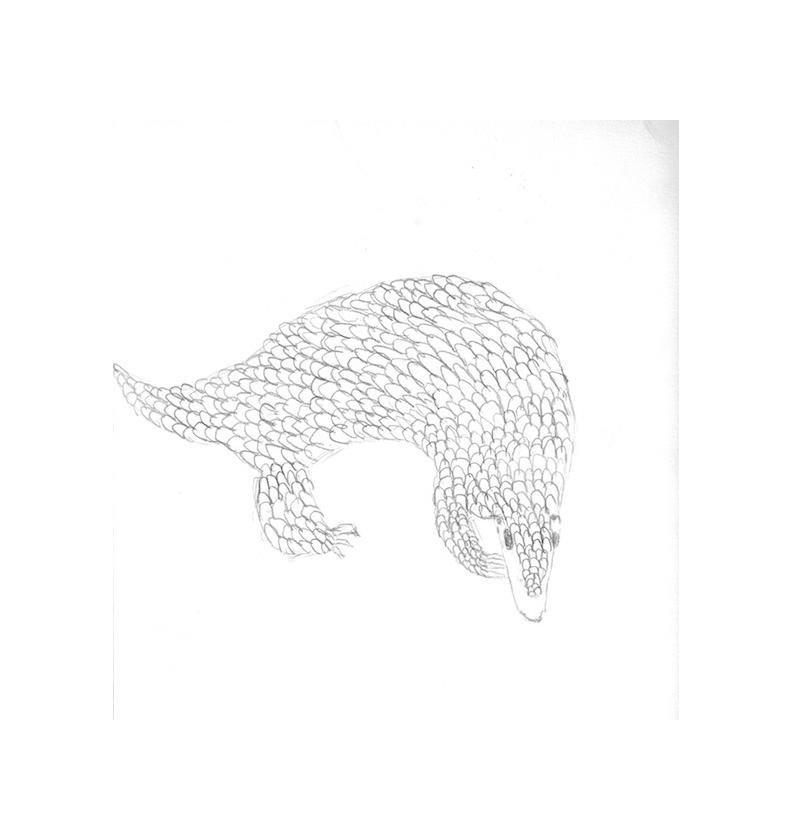

Their unique features include bodies covered in keratinous scales (which make up 20 percent of their total weight) and incredibly long tongues. Pangolins are toothless, can consume 70 million ants per year and live for 20 years on average.

The scales provide some means of protection against traditional predators, which include various python species, leopards, tigers, lions and wild dogs. Pangolins’ most dangerous predator is the only species that hunts the pangolin and that itself is not vulnerable or endangered – humans.

While all of the African species are vulnerable, all four Asian species are endangered – the Sunda and Chinese critically so. They are particularly vulnerable to poaching. In some Asian countries, their scales are valued for medicinal purposes, and their fetuses are considered delicacies.

Every year, tens of thousands of pangolins are killed for trade in scales or flesh. As Asian species disappear, the price for poached pangolin is rising sharply worldwide. Consequently, African species are now facing pressure.

Pangolins also suffer from habitat destruction. When forests are cleared for uses such as palm oil plantations, the pangolin are exposed, and easily picked up and bagged for later sale.

In all eight species, mating pairs typically only produce a single offspring annually. The young remain dependent upon their mothers until they are sexually reproductive – up to two years in some species. Because of this, hunted pangolin populations do not recover as rapidly as species with faster reproductive cycles. The low rate of reproduction and the fact that they do poorly in captivity also means that farming them is not a solution.

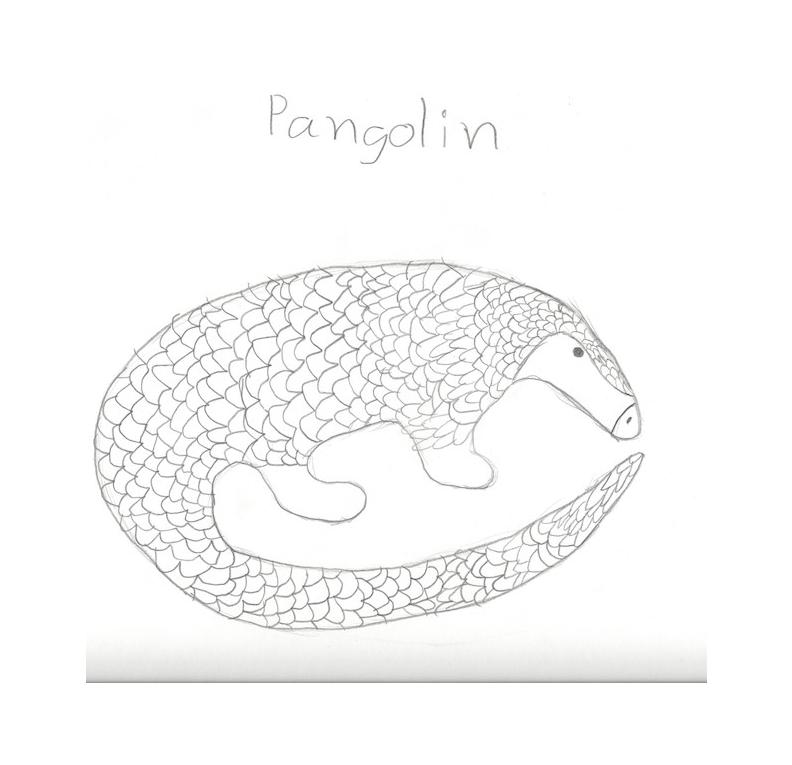

At the end of their presentation, Sage and Keira invited the students in the class to draw the images of pangolins that accompany this article. They also listed the things that people could do to save pangolins:

1. Try not to eat unsustainable palm oil

2. Donate to groups like Save Vietnam’s Wildlife and Education for Nature Vietnam

3. Learn about them and tell friends and family about them

4. And finally, DON’T EAT THEM!

I like this list. When I look at the larger issues around species conservation, I am struck by the enormity of the challenge. I get so caught up by all the biodiversity we’re losing that I forget how much we can do to help one species. Instead of becoming overwhelmed by the problem, Sage and Keira created small solutions that seem doable and could really make a difference for these amazing animals (and many others).

Without realizing it, they’re following the example of local NGOs, the IUCN SSC Pangolin Study Group and environmental activists such as Robert Hii. Hii has a number of projects that directly and indirectly protect pangolins. Thanks to funding from the German SAVE Wildlife Conservation Fund, he has worked to increase community involvement and prevent poaching in the Kalimantan area of Borneo. He also encourages those in the palm oil business to reduce deforestation and protect pangolins.

Hii helped facilitate a study of the Sunda pangolin in Sabah, Borneo, which was conducted through Cardiff University and funded by Lush Cosmetics. The region is particularly important for conservation efforts because, as Hii notes, “there is a strong conservation movement … in Sabah. It is one of the better conserved regions in Borneo [and] conservation efforts there have the support of the Minister of Tourism, Culture and Environment, Datuk Masidi Manjun.” Manjun is outspoken on behalf of conservation efforts, and the state-run Sabah Wildlife Department is adept at solving issues of human/wildlife conflicts in a manner that protects the wildlife.

Like Sage and Keira, Hii and his colleagues start by making people aware of the issues. They then break the problem up into pieces that can be tackled.

According to Hii, “Once people find out about pangolins, most get hooked as it is such a strange and wonderful-looking creature. What we should all be doing is simply to let all our friends know: there is a dragon that exists among us and it needs our help.”

Sage and Keira were certainly hooked. Sage is more than ever committed to avoiding palm oil. She is also saving money to donate and has convinced me to give our swear jar cash (generally filled by my contribution of quarters) to pangolin rescue efforts.

The activist nature of children is driven by their optimism about the future. For me, this optimism can be difficult to sustain. But I’m inspired by my daughter’s desire to prevent a depauperate future, by the daily work of Hii and others like him, and by the drawings you’ve seen throughout this piece.

I have never seen a pangolin in person. Neither have my kids or their friends and classmates. Children are, however, wonderfully able to engage with species outside of their direct experience. These kids will not forget the pangolins, and this engagement adds to their understanding of the richness of the world. In turn, their understanding of these mammalian dragons may lead some to make the choices that help, in some way, keep pangolins in the world.

References

Liu Y and Q Weng. 2014. Fauna in decline: Plight of the pangolin. Science 345: 884.

Zhou ZM, Y Zhou, C Newman and DW Macdonald. 2014. Scaling up pangolin protection in China. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 12: 97-98.

Additional Resources Regarding Pangolins

Education for Nature Vietnam

Photos are copyright protected and may not be reproduced without permission. Unless otherwise noted, photos are used with the permission of Jennifer Calkins and the students of Ms. Day’s class.

Jennifer Calkins Jennifer Calkins, PhD, MFA is a student at UW school of Law. She was previously Voices for Biodiversity’s interim Managing Editor, anevolutionary biologist and a writer. Her writing and multimedia work has been published in a variety of venues from peer-reviewed scientific and humanities publications to literary journals to the New York Times’ online blog Scientist at Work.