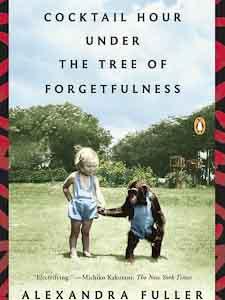

Unlike Fuller’s first book, the memoir Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood (2001) – the cover of which shows a photo of the young Alexandra herself, fists balled, mouth wide open, caught in mid-temper tantrum – Cocktail Hour is not so much about the author. Although it spans the same territory – the Fuller family’s life on several farms in southern Africa during the long period of bloody civil war and political unrest that coincides with Fuller’s childhood – this, Fuller’s fourth book, takes a different stance. It is, in fact, not a memoir at all but a biography, an honest, loving portrait of Fuller’s courageous and enchantingly eccentric mother, who refers to herself majestically throughout Cocktail Hour as “Nicola Fuller of Central Africa.”

The bestseller Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight, as it turns out, was not a big hit with Fuller’s family. Her father, Tim, and her older sister, Vanessa, refused to even read it (falsely alleging their illiteracy), while her mother, an avid reader, panned it. Nicola repeatedly calls it “that Awful Book” (always in initial caps) written about her.

“For the millionth time,” Alexandra argues near the start of Cocktail Hour, “it’s not awful, and it wasn’t about her.” Seemingly, then, in an effort to redress this situation and resolve the misunderstanding, this new book, written ten years after the first (and now that Fuller herself is the mother of three), is all about her mother. It is drawn primarily from a series of long interviews with her mother, many of them held during cocktail hour at her parents’ current fish and banana farm on the Zambezi River in Zambia, under a certain tree. “It was a tree of modest height, with a rounded spreading crown of leathery dark leaves and drooping branches,” Fuller writes, “full of birds.”

A local tribesman, Mr. Zulu, explained the tree’s meaning to Fuller’s mother before they chose to build their house there:

This is the Tree of Forgetfulness. All the headmen here plant one of these trees in their village… They say ancestors stay inside it. If there is some sickness or if you are troubled by spirits, then you sit under the Tree of Forgetfulness and your ancestors will assist you with whatever is wrong… It is true – all your troubles and arguments will be resolved. Our heroine, Nicola Fuller of Central Africa (née Nicola Christine Victoria Huntingford), was born on her mother’s family’s estate on Scotland’s Isle of Skye on July 9, 1944. Two years later, she and her parents immigrated to Kenya, where she grew up and later met Tim Fuller, an Englishman just out of college and traveling around the world. Tim fell in love with both beautiful Nicola and breathtaking Africa, and (except for short visits to Britain) he hasn’t left either since. Despite the horrors of war and a long series of personal tragedies – losing three of their small children to illness and accident, losing their farms, losing (for a time)their bearings – they remain in Africa because Africa, they feel, is where they belong.

During one brief stay in England, after their young son Adrian had died of meningitis in Rhodesia, Alexandra was born. But Nicola couldn’t wait to get back to the Africa she loved. Fuller writes lyrically of her mother’s memories of their return voyage:

As Africa swelled into view, she [Nicola] pinned herself to the railings of the deck and felt the dampness of the last three years lift from her shoulders. When a hint of shimmering purple ribbon on the horizon bespoke Kenya, she held her face to the west and tried to inhale the perfect equatorial light. And as the ship veered around the tip of Africa, Mum held me up to the earthy, wood-fire-spiced air. A hot African wind blew my black bowl cut into a halo. ‘Smell that,’ Mum whispered in my ear. ‘That’s home.’

I confess, when I reached the chapter “Olivia,” two-thirds into Cocktail Hour, I thought I would have to quit. The memories of Fuller’s baby sister’s drowning were still painfully vivid in my mind from the first book. But that book was written by a much younger woman, still haunted and burdened by the misplaced guilt she felt as a little girl. This book’s author is older and wiser; she knows now that she was not responsible for Olivia’s accidental death.

Cocktail Hour is a triumph – beautifully written, poignant, funny and wise. Those who have read and enjoyed Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight are sure to appreciate revisiting those true stories and seeing them this time from Fuller’s mother’s perspective. The two books go hand in hand; but, like a mother and her grown daughter, they can stand on their own.

And for me, whose books always feature my own beloved Africa, Cocktail Hour also subtly raises deeper questions, such as: Who is African? Who has the right to write about Africa and from whose point of view? Who owns Africa’s stories? And don’t those Trees of Forgetfulness contain all of our ancestors? My suggestion is to read Fuller’s new book – from cover to cover and between the lines – and judge for yourself.

Photos are copyright protected and may not be reproduced without permission. Copyright information for images are as follows: 1) Book cover, photo used with the permission of The Penguin Press; 2) Zambia Baboon, photo courtesy of Damien Firmenich and used with the permission of Flickr Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0 Generic; 3) African Sunset, photo courtesy of Kathryn and Jonmikel Pardo.