"Tomorrow, I'll introduce you properly to the three girls," Teresa says, referring to the elephants. "And don't run into the blind buffalo in the garden on your way to bed." I'd been forewarned that he is pretty hard to detect in the dark, easily mistaken for part of the mountain range in the distance.

It's been over a year since I met Teresa on a horseback safari in the Hwange Wilderness of Zimbabwe, Africa. Now I've arrived at her farm, Wasara, in the southeastern lowveld of the country. At least it was a farm – a 6,000-hectare cattle ranch actually, low rolling grassland punctuated with rock upcroppings, stands of ancient trees, wetlands and dams. Over the last decade, however, with the relentless encroachment of the politically-motivated land invasions, the farm is now a small parcel of 400 hectares and part of the Chiredzi River Land Conservancy, theoretically a place of refuge. But the flood of new settlers continues unchecked and has decimated the original Wasara ranch land as immigrants set fire to the grassland in attempts to clear it for crops, cut down hardwood trees for cooking firewood, and poach the wild animals practically into non-existence in their desperation for food.

For the first time, I hear in detail from Teresa’s husband and see for myself how these newcomers have been re-located from elsewhere by the government. They are disoriented, left to grow crops on the least arable land in all of Zimbabwe, land that is different from the places they came from and unresponsive to the farming methods they have practiced historically. Crop yield is sparse and food production negligible. Calling them settlers is ironic under these circumstances. Apparently, organizations pour food aid into the area without worrying about sustainability and practicality. Local white Africans and conservationists question the value of organizations stepping in without addressing the bigger picture of a country in shambles.

Listening to Teresa breaks my heart. The formerly productive ranch supported several hundred workers and their families who made their home on the property. When the government reclaimed the ranchland, cutbacks in staff had to be made. They are the invisible casualties of the land invasions, 90 percent of them dead now from political violence, HIV/aids, tuberculosis, malaria, malnutrition or the aftermath of homelessness.

* * *

Seven white horses, in a herd of 10. I have come out to see them by myself, seeking a familiar place to put my hands. As a good houseguest, I’ve tried to maintain my composure since arriving in the lowveld, but being alone with the horses has loosened a deep reservoir of darkness. Stroking Ticker’s satiny, white nose, we breathe out simultaneously, and she spatters my light-coloured shirt with a spray of dusty snot. Wiping my own nose on a sleeve adds a damp brown streak, then tears come as my forehead finds a resting spot against her neck. I am up against the ingrained compulsion to make sense of things, my own radar that seeks patterns and frequencies and revelation. Sadness comes up from the ground and presses into my chest.

The beauty of the horses on the ranch contrasts so painfully with blunt immersion in the disaster evident in the surrounding landscape and in every conversation. There is no escape to another more palatable reality; two weeks ago, eight remaining giraffes kept safely enclosed from wandering by an electric fence were sprung by poachers from the acre-big paddock and have not been seen since, presumably victims of the illicit animal trade. Wasara, and everything a conservancy stands for, is under siege.

* * *

Teresa's son, home on holiday from veterinarian studies in Australia, is a breath of fresh air. He is betting his education on a turnaround in Zimbabwe’s fortune and being able to contribute what he can to a restorative future.

* * *

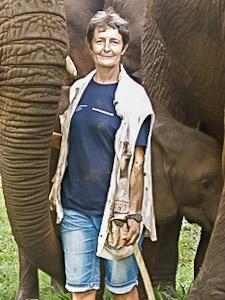

Animals not living in the wild are dependent on humans to feed them, and they enjoy consistency. Teresa wears a photographer's canvas vest at morning feeding time, stuffing each pocket with fruit grown on the farm expressly for the elephants. We walk through a lush plantation of sugar cane stalks and trees heavy with bananas, papayas, grapefruit and oranges. In the centre is a large square plot of pumpkins that continually grow from the elephant manure dumped there each day.

She invites me to ride Chitora, the biggest of the three elephants, from her nighttime paddock way out to the daytime grazing grounds. The idea of climbing onto her is exciting, but once I am actually sitting on her I see just how much further down the ground is than from the back of a horse. I’m unnerved at first, and she senses my bit of apprehension as I try to find the right spot to settle myself. Now Chitora’s huge ears blanket my legs on either side of her head, and I grip the top edges to keep my balance. I am doing my best to relax and feel the physical contact of my body with hers. As the days pass, I will feel more and more at home with her.

Thank goodness Beebo, her handler, is walking beside us as we approach the wide gate. I hear thunder rumbling in the distance, and a few seconds later I can feel its vibration underneath me; I wonder if it will disquiet Chitora. Beebo looks up and nods; it is not thunder, it is Chitora sounding her way across the field, sensing the truck coming our way. Standing still at the gate till the vehicle passes, her low frequency vocalization penetrates my body. I feel stirred and energized in an oddly familiar way.

I remember lying in the circular sanctuary of Hollyhock Retreat Centre back in Canada while two musician friends from Australia played their didgeridoos over the energy meridians of my body. Now, I am here in Africa with the same vibratory sensation running through me.

We pass the afternoon keeping track of the girls in the bush so they don't break through the electric fences, which they can cleverly do by putting a log or big stick against the fence to lower it to the ground so they don't get shocked by the live wire as they walk over. By now, I am comfortable sitting on the ground as they move past, near enough to touch a foot, skin like thick quilted leather.

Later that night, Teresa gives me a book to read: The Fate of the Elephant. The author, Douglas H. Chadwick, describes his return to Hwange National Park in 1990. I am tickled to be reading familiar place names from our safari there last year. All of sudden, I sit up in bed and hold the book closer to the light. Chadwick writes:

My eyes blur with tears of recognition.

And the more I awakened, the more I began to realize how much I had sealed myself off in order to cope with Asia. Unconsciously I had erected baffles against the all-consuming tidal wave of human culture until, by imperceptible degrees, I had grown numb. I had forgotten what it was like to be wholly immersed in the sensations of wilderness.

Suddenly, I could feel it in the hoof beats traveling through the ground beneath me as I lay under my blanket. It was as real as the red and gold eyes that sometimes circled in toward the campfire, and the singing in my blood said it was within me too. It could be kept real. It had to be; I could not imagine my own life without the deep currents of nature flowing close by. That was why I worked in conservation. It was why I had undertaken the elephant story. I remembered.

The old feeling returned of being among not just animals but animal tribes and nations.

Photos are copyright protected and may not be used without permission. All photos are courtesy of Orianne Lee Johnston.