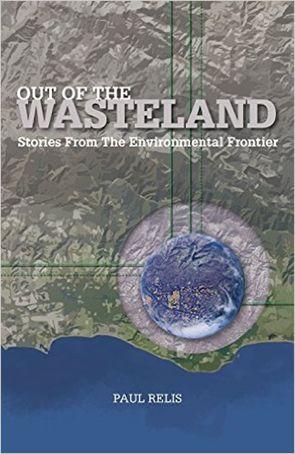

There are many books about environmental issues and the environmental movement, but what really sets Out of the Wasteland: Stories from the Environmental Frontier apart is that it both parallels the development of the entire US environmental movement and has a personal story at its core. We follow and learn alongside author Paul Relis as he works toward a post-oil, landfill-free future. The story begins with his first steps into environmentalism after the massive Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969, as founding Executive Director of the Community Environmental Council. It proceeds through his years as an executive at the California Environmental Protection Agency and teaching Environmental Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, all the way to his current career in cutting-edge environmental technologies.

How did you react to the Santa Barbara oil spill at the time?

Seeing the Santa Barbara coastline for the first time as a student at UCSB, I was enamored with its beauty — I couldn't believe there was such a place. When the oil spill happened, it was this suffocating blanket of black, oozing on the beach. It felt like the death of this pristine place that I loved. It's probably difficult for people today to understand the scale of that event and how it affected the nation, but it was front and center on the nation’s news for days.

When you’re presented with a catastrophe that relates existentially to who you are and all the things you believe in, where do you go? All through my childhood, I’d experienced the loss of places. Subdivisions taking over wetlands, farmland replaced with commercial developments, one after the other. I think that's what causes some people to react as strongly as I did and want to save this marine environment.

When did you realize that this would be your professional path?

I had a lot of anger, as did fellow citizens from Santa Barbara. There was this one moment when I was in a single engine plane and the pilot took me over the spill. I literally looked straight down and saw this massive, under-pressure upwelling of oil coming to the surface. I was mesmerized by the sight and a little voice said, “This is going to change the world — and I want to be part of that change.” I had no idea what that meant, of course, just that there was anger, there was passion and there was that sense of “I'm drawing the line here.”

My first impulse was activism, but I quickly realized that it wasn't my path. It was late in the turbulent 60s and, watching these phenomena happen, I just thought, “Paul, you'll burn out and you won't be able to sustain yourself. You'll do it for a couple of years and then you'll have to get out because it'll be so stressful and negative.” So I was taking the view that I had to be part of creating an environment, not just talking about it. I knew I was intrinsically a builder and I wanted to build the future.

I spent 20 years in the nonprofit sector, 7 years in high-level government and the last 16 years in the private sector.

In your book, I could feel the camaraderie of your group [at the Community Environmental Council], people who wanted to make a difference, who had a shared vision, shared dreams and the shared pain of defeats.

To a degree, we were onto the basic themes of what you now call sustainability nearly 50 years ago — solar energy, gardens and green buildings, we engaged in all of that and we didn't do it in a cursory way.

We built buildings through trial and error, gardens that worked or didn't. And yes, there was great camaraderie.

We also had to deal with the policy side and the politics. Everything we did required a decision by a political body to make or break it, and that's often overlooked. You don’t often read about the political connection, but everything we did required a vote — by our board of directors, by the planning commission, by the city council, by the board of supervisors. The book follows a series of those types of decisions on an ever-bigger stage.

How difficult was it going from the NGO approach to working within the government?

I was not by nature someone who was at home in politics. I didn't fully appreciate power relationships and I met a whole different strain of human being in the political sphere: people with big ambitions, people who could easily get in your way and try to stop you if you got in their way. The political aspects of being in a high-level government position were very sobering. While I could excel in the policy and doing the work, I was out of my element in the political world. It took me several years to figure out — and I took a few hits as I worked through my naivete. But I did figure it out.

At one point in the book, you talk about a period of frustration before you realized you needed to step back and get more balanced. What did you do?

As an English-Humanities major, my resources were the ideas of writers and philosophers. I was also a student of the classic Indian spiritual text, The Bhagavad Gita, which is a treatise about the art of detachment. The idea of detachment appealed to me, to disinvest in the emotional side. I had to develop a steely inner life that would allow me to endure disappointments and frustrations so I could take the long view. Whereas if I were captive to instant results, it would be “Oh, they didn't pass that law this year, I'm done, I'm out of here.” If you care enough about something and have the right attitude, you endure.

I think the trick for anybody who sees themselves in a role of change is recognizing what's going to keep you healthy. That very point is often the least examined aspect of the work. People would just be consumed by the action and lose perspective, and then lose energy and eventually lose the will.

But there are fights that require intense struggle, and I chose a path where the frustrations and other things that I endured might have a payoff, like building a green building. That was a creative act and it felt beautiful. Or in the early years building recycling centers or planting a garden on city land. If it got approved, it would be permanent. It wouldn't be rubbed out because you were on land borrowed from a developer. The seeds that we were able to plant grew, and they endured. Most of the work that I was involved with endures to this day.

Most people I worked with in the 70s and the 80s saw the corporate world as the enemy. How did you view it?

I was in a comfortable position as the head of an NGO that was doing well, but I decided that I had to put myself in a different and, for me, toxic environment. I needed to understand how regulation is made. Is it an art? Is it a crude, bludgeoning fight between interests? That came to be of great interest to me and I was willing to put myself in harm's way.

The same was true with the transition to business. Being entrepreneurial, I said, “We need to find a solution and get to a post-landfill world. If I'm going to do that, I need to be in a business structure where there's the capital and competence to do and build things.”

Fortunately, my objectives resonated with the views of a successful business owner. He was not an environmentalist at all, but he had a successful company and he liked the vision I had. I’d never worked in an operations company and I was given a pretty tough baptism. I came in as a top state official with a good reputation, but they were an operating company so it was, “What the hell do you know? What value are you going to contribute or are you going to be a drain on the company?” And I was a drain for a number of years and I had to deal with that so that when the right time came, I could implement my plan.

I knew the owner and we shared a vision, but no one else in the company shared it and they were looking for me to trip and fall. It was not the camaraderie I’d had in the NGO at all, it was like I was on my own and no one was going to do any favors for me.

Can you tell us about your move to technologies for waste management?

I began my career with a lot of interest in building and recycling, but increasingly my focus was the broader waste management field. I taught at UCSB in that field. The subject may be mundane for many but I would argue that, like energy, waste is one of the core problems of our time — whether it's waste debris in space, plastic bags in the ocean, micro particles or air pollution. It's all waste related.

I was fascinated by the challenge of what could we do with organic waste, garden waste, grass clippings, all this stuff that goes into landfills and produces methane, an extremely potent greenhouse gas? Could we find some long-term use for organic waste that would address multiple environmental concerns such as short-lived climate pollutants (for example methane gas), soil health and air pollution from the combustion of fossil fuels?

I had been heavily engaged in leading the efforts of the California Integrated Waste Management Board (now called CalRecycle) to find markets for recyclable materials, but that turned out to be a rather big disappointment. I realized that we weren't really recycling, what we were doing was collecting and exporting dirty commodities to Asia and specifically China, where they would use our raw materials, our discards, to produce packaging and then send the finished goods back our way. In the process, all that raw material was translated to pollution in China and even in the air that would blow over to California from the paper and other plants consuming our recyclables. It wasn't the kind of environmentalism — if you want to call it that — that resonated with me.

Something that comes up a lot in the environmental movement is frustration about large environmental organizations becoming almost corporate themselves.

Absolutely. We’ve had a number of issues come up in California. I'll give you one example, and it's an ongoing and pointed issue. There is a view now that everything in the world can be done all electric with solar and wind. It has reached a point where people think we shouldn't do anything to encourage any expansion of gas infrastructure in America, even if it’s renewable gas from recycled organic waste and produces a zero or minus carbon footprint. Well, the company I'm involved with is making gas from organic material that was previously going into landfill and producing methane gas, yet is now powering new engine technologies that are as clean as solar-powered electric will be in the California grid in 2045, when the grid is expected to be all renewable energy-based.

Our technology is about as clean as anything I've been a part of. It's as green as it gets. I mean, we're taking raw material that's local and we're producing fuel — renewable gas. Its emission profile is carbon-negative. We're also producing soil products. So we're addressing air quality, recycling, keeping stuff out of landfills and transportation, and we're doing that all in an entirely green way. But because of the antipathy toward gas as a concept, many environmental groups have staked out a position that seems unaffected by science. We can prove what I'm talking about — it's not conjecture.

I'm in total agreement with making California, and indeed the nation, powered with renewable energy. We need to do this for our health and our existential survival. All I am saying is that in the push to become renewable, solar and wind can and should be done in tandem with niche technologies like the one I’ve described. There's what I call a pattern language of sustainability, which might have 90% solar and wind energy with the balance of 10% of coming from utilizing renewable energy from recycling dairy manures, biomass and municipal organic waste. You need all of those. Even solar doesn't come from nowhere. Solar cells require mining of the minerals used to build the components of a solar energy platform, the cells, batteries and perhaps other components. Solar is a hell of a lot better than fossil fuels, that's for sure, but it's not a singular solution and its development is by no means pollution free.

It seems everything has a cost and a tradeoff, and it's difficult to balance that. Environmentally, how would you compare the world today with the 1970s?

If climate change denial had not become national policy, I would feel a lot better! Today’s tools for sustainability compared to what I dealt with — well, they just weren't there. The solar collector of today is light years ahead of what it was when I first experienced it.

Today, the tools for truly achieving sustainability are with us and that is breathtaking. I think it's a huge achievement and it’s the result of years and years of policy, legislation and regulations that created opportunities for entrepreneurs to respond to modern needs, like the oil industry did 120 years ago. I think we could accomplish that with post-oil technology. That's no longer a dream.

You wrote, "Unlike decades ago, we have the tools, the technologies, and the companies to build the post-oil age."

In so many respects, this should be the most exciting time to be on the planet. In California, it feels like we are doing the work, but unfortunately it's not a shared vision. Twenty years ago I was dealing with moderates, conservatives, everyone, and there would be broad agreement on the outlines of what to do. Today, we've created this implacable ideological divide, where the environment has been viewed with hostility in the highest office in the land for the past four years.

Many of the environmental policies that came after the Santa Barbara oil spill came from Republican administrations. There was no conflict. It was not viewed as the enemy. And now it is and that's really distressing. We had this almost complete trajectory moving out of the oil age and into sustainable urban patterns, and that’s now a hell of a fight. And it's ugly. It's also depressing for people who've been in this work for a long time, like “Yeah, we made all this progress, but politically we've made no progress.” We're regressing back to almost a pre-environmental state in spite of all the evidence.

I think the leadership has to come from activists, policymakers and legislators for setting fair ground rules and parameters on behavior, and let business do what it does as long as it's within those parameters, but we may be in a situation where business is over-influencing the policy and the legislation.

Yes, particularly in what I call the destructive commodities industries. Because they're still very powerful and they will remain powerful as long as they are allowed to be disproportionally powerful.

I’d like to get your thoughts on the controversy about the pressures of population growth. A lot of people argue that population is not the problem, consumption is the problem.

I think consumption is at the heart of the world's dilemma more than population per se. It's like a disease, but it's a feel-good disease. You get to buy and enjoy all these goods. It feels good, but it's killing you. You don't know that it's become a virus that's resistant to everything. Consumption is resistant to everything we've thrown at it in the environmental movement.

China had a billion plus people years ago — but they weren't consumers. And now they're consuming as we have in the US over the last 50 years. They and other Asian countries have become a new consumer wave. I’m not saying that they should be denied their day to enjoy prosperity, but they and we need to face the fact that our combined consumerism will likely prove our demise. We must find ways to be prosperous without consuming our birthright and that of future generations. Technology will be of enormous help but technology alone will not save the day. Ultimately, the challenge is a human nature problem and not a technological problem. We know what to do.

What advice would you give to a young person considering pursuing environmental issues as a career today?

If I were young today, I'd stake a ten-year effort on reforming the regulatory process in California. It's sclerotic and it's producing unnecessary costs. I’d tell the old me to really pay attention to how to regulate so you don't waste capital. Vested interests in the regulatory system we've created in California — the lawyers who benefit from it, the environmental groups who know it and benefit by it — are all part of the problem. Their livelihoods are tied to a system that really needs to change. I hate to see money wasted and some of these interests think that as long as you can get the policy through, it doesn't matter if it isn't as efficient as it should be. And business people would really appreciate a better value regulatory system — they might even embrace it. So that's one area for young people who want to be in government that would be a potentially productive path: they could devise that next system. It would be challenging and bold, and it's needed.

There are also huge opportunities to be an entrepreneur or get involved in a company that provides goods and services that the public seems to want and that the regulatory system wants to deliver. These are the outside-of-the-box people. The liberal arts have a role to play in this, and it shouldn't be short-sighted. It's not all going to be done by engineers and computer scientists.

You did a great job with Out of the Wasteland — it’s for anybody interested in the environmental movement and how it evolved to learn about it in a way that no other book can give them.

Thank you, I enjoyed writing the book. It’s something I had to do. It’s not an environmental polemic so much as a very personal story told in a way that is meant to resonate with people who don’t necessarily consider themselves environmentalists as well as those who do. The stories I share begin on the smallest of stages, a little office in a little town with a group of young and old alike traumatized by an immense oil spill off our shores. With almost no resources, just our beliefs, imagination and ingenuity, we built a significant environmental platform in Santa Barbara. The storyline extends to Sacramento, Asia and Europe and then focuses on the development of a new, hopefully world-standard recycling technology. The book is now nearly five years behind me. There are several chapters that I’d like to add to it.