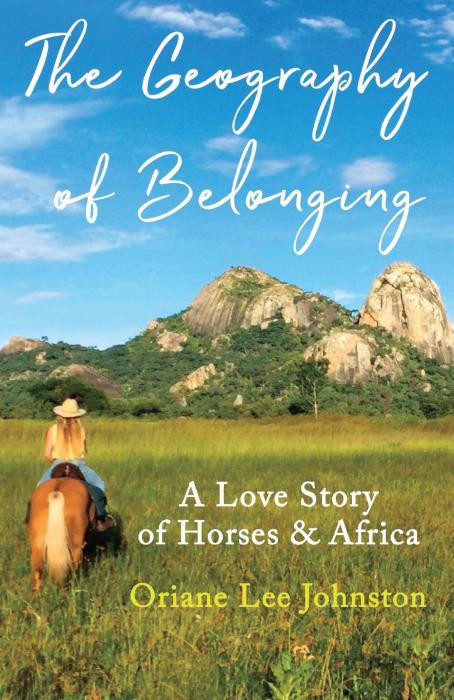

A conversation between Voices for Biodiversity Senior Editor Debra Denker and author Oriane Lee Johnston about her book, The Geography of Belonging: A Love Story of Horses and Africa.

Oriane, I experienced your book as a love story on many levels, not just with Stephen Hambani, the Shona horseman in Zimbabwe who tracks wildlife on safaris on horseback. It’s also, as the subtitle says, a love story with horses, with Africa, with Earth itself. Tell us a little bit about how you fell in love with Africa.

Well, Debra, you can imagine sleeping on the ground under the stars where there are no jets overhead. The sky is as pure and dark as the night sky gets. You hear all the insects, animals, rumblings to the farthest distance, and you feel the pulse of the earth as you lie on the ground. That was really the beginning of the love story.

After I returned to Canada, I asked Janine Varden of Ride Zimbabwe, “What happened to me in Africa?” She is originally from Australia and married a Zimbabwean safari guide. “You’ve been bitten by the Africa bug and it never goes away. It stays in your system forever.” The love-bug bite happened on that first horseback safari where I met Stephen and the Vardens and we rode into the wilderness of Hwange National Park.

It means the terrain where one feels most at home, both literally and figuratively. There’s a passage in the book toward the end that the title comes from — it's quite an intimate passage:

“I found myself initiated, brought into the resonance of Earth Africa through Stephen…

“I thanked him for that when we parted company last year in May, for bringing me into the Earth of Africa through his body — a tree, a flower, a river, a horse. He listened, as if this is normal — which it is, in the geography of belonging.”

A Canadian man who recently read my book asked, “Do I, too, need to go off to an exotic place to find love?”

I thought about that and responded, “I wasn’t looking for love at all. I was doing what I most love, in a place that is very compelling, an archetypal landscape.

“What are you passionate about? Do that. Where on the planet calls you, or where in Canada or where in your neighborhood calls you? Be there and do what you love most.”

That's beautiful. British writer Doris Lessing, who grew up mostly in what is now Zimbabwe, once wrote:

“I believe that the chief gift from Africa to writers, white and black, is the continent itself, its presence which for some people is like an old fever, latent always in their blood; or it’s like an old wound throbbing in the bones as the air changes. That is not a place to visit unless one chooses to be an exile ever afterwards from an inexplicable majestic silence lying just over the border of memory or of thought. Africa gives you the knowledge that man is a small creature among other creatures, in a large landscape.”

Photo by Janine Varden

Tara Waters Lumpkin [founder of Voices for Biodiversity] and I both have that feeling, as you know. We traveled in South Africa together for six weeks in 2009, which resulted in the birth of Voices for Biodiversity. We were originally introduced by someone who knew we both had a connection to Africa and specifically to traditional healers. Tara did her fieldwork for her PhD dissertation on Perceptual Diversity learning from Namibian and South African traditional healers.

Oriane, what drew you to Africa? In the book you say that you had always wanted to go there. And that when your life changed suddenly, you were ready for something completely different. You write that googling “Africa + horses + volunteering” seemed perfect, looking back. When you were a child, did you think about Africa?

Yes, oddly, in fifth grade I had a most vivid dream — of sitting in the back of the school classroom, hearing distant thundering coming closer and then massive voices. I imagined it was an African tribe coming to collect me. Of course, it was straight out of Tarzan back in those days and very frightful at the time.

But it stayed with me, always, and after being in Africa, I came to see the dream as a deep call. The book describes how I met traditional healers, svikiro, shamans. That continues and has deepened my relations with the spiritual ecosystem.

The second thing predates even thinking about Africa as a realistic possibility. In the early 2000s I did a series of GIM [Guided Imagery with Music] journeys. Rather than using psychedelics to induce deep states of consciousness, specially curated music does that. And in every journey, I was led into archetypal Africa.

That's a strong connection. I remember when I was in sixth grade, there was a National Geographic cover picture of a San man, who were then called Bushmen. I researched more and wrote a report on their culture. I longed to go there, and would sit with the world globe in my lap and look at all the places I wanted to go and learn about.

Yes, I can imagine! Africa, the motherland, where humans originated.

That happened in 2010. The story in the book goes through 2016. I have returned to Zimbabwe again and again, including this year, 2023, following an absence during the pandemic. I must say this travel requires a reckoning with ecological costs each time.

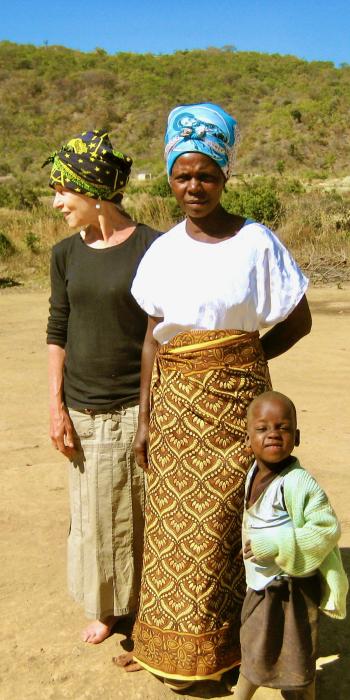

Initially, I was very fortunate to have several months in the Mavuradonha Mountains in north central Zimbabwe with Shona horseman and wilderness guide, Douglas Chinhamo. I returned in subsequent years to ride with Douglas exploring that ecosystem. That was not only a personal introduction to the cultural landscape of his people, but also orientation to the trees, the plants, their medicinal and traditional uses that brought the wilderness alive, completely alive. Or rather, brought me alive — radically alive.

In such a different geographical place, there is no familiarity. Sometimes when traveling, your mind is inclined to seek the familiar. And when there isn't any, that seeking is put aside, the mind falls away and a new world shows itself.

Photo by James Varden

At one point the horses were moved away from Mavuradonha. After some exploration in different locations, the horseback safari outfit is back in Hwange National Park where my story began. There’s a newly created tented camp with outrides deeper into the wilderness.

After the horses left Mavuradonha, Douglas was out of a job. I introduced him to Gus Le Breton, who is known as the African Plant Hunter. The two of them know literally everything about the native flora of Zimbabwe. Now they're working together on a permaculture project and on restoration of the Mazowe Botanical Reserve. The botanical reserve is an intact ecosystem, so the plan is to open it to researchers and visitors for educational purposes in a way that protects and sustains the biodiversity.

In my experience, foreign mining is the threat. In the book I tell the story of a trek into that wilderness and seeing the chromium strip mining happening just outside the boundary. It’s shocking, walking over that ground, and it’s especially sorrowful since it’s without regard for the villages, the communities, the watercourses, the wetlands, everything.

And then, as described in the book, the Mavuradonha wilderness became a Zimbabwean National Heritage Site, which is the first step toward becoming a World Heritage Site. It’s a protected “cultural landscape,” which includes the rushanga, the sacred shrines from days gone by that remain alive with spiritual power. The Shona spirit mediums, the svikiro, have a responsibility for the rushanga in their area. Nonetheless, even nowadays the antipoaching patrols come across illegal foreign prospecting in the National Heritage area. But the current stewards of Mavuradonha are vigilant in apprehending the prospectors.

Hwange, on the western side of the country, has been a very well-known national park since 1950. The terrain is flatter, more open plains and woodlands, a completely different ecosystem than the Mavuradonha mountain rivers, escarpments, waterfalls and gorges. The plains of Hwange are without surface water and in the dry season rely on human-made watering holes to sustain wildlife in the park. In recent decades the diesel-powered water pumps have been converted to solar power.

Good question! Horses came to East Africa and southern Africa with the British and the Europeans for traditional equestrian pursuits including polocrosse and for riding out to tend “their” massive farms. Horse safaris in Zimbabwe first started in the 1980s in Mavuradonha and that’s an entirely different scenario because horses are prey animals, biologically wired to flee from predators. What's most fascinating is how the horses are trained for encountering the wild animals, both predators and the large herds of other prey animals like zebra, giraffe, elephant and the country’s sixteen species of antelope.

The horses get accustomed to the bush and then, bit by bit, to the wildlife. For example, wildebeest are relatively safe, so the safari riders can get the horses used to walking up close to them. Cape buffalo can be dangerous, requiring more caution and distance. That's where the expertise of the guides and the horsemen come in. They're extraordinary.

On my website there’s a video called Wildly Familiar: Nature’s Sixth Sense, which I did at a safari camp on the Ngamo Plains in Hwange National Park when I was there in 2019. The guides in it, Jamie and Clever, were unsure around the horses, intimidated by them. So, we did an Equine Guided Learning session alongside the horses grazing in the field — paying attention to the physical sensations and energy in their own bodies as they approached and interacted with the horses. I figured this is what safari guides do naturally with wildlife in the bush. Afterward I asked the two guides: “What is the same, or different, for you with the horses compared to tracking wild animals in the bush?” To their delight, it was very similar.

The main thing they have in common is that they're both prey animals, so they have the same sensibility and attunement to predators. Because zebras are no threat to horses, the horses are quite comfortable and so are the zebras; just make sure when approaching to go slowly so as not to startle and you can ride alongside zebras.

Trust them. Trust my guides.

Both of them. Trust your literal human guides on the ground and trust the spirit guides. In the book, my son and I meet the svikiro, the spirit guide for the sacred mountain who said, “You are safe here. Safe everywhere in Zimbabwe.” This promise of protection didn’t make me less safety-conscious. I actually became more attentive to my surroundings. Maybe that’s what that ceremony with the svikiro was for — I received a transmission of attentiveness to the wild landscape.

When my son and I were in the bush camp with the horses, Douglas’ wife, who was very pregnant, and her sister, who had twin babies, walked a couple of hours from their village to the camp, each with a baby on her back. When it was time for them to go home, my son, in his mid-30s at the time, said, “Oh, I’ll walk you partway back. I know the way because we’ve been there on horseback.” My friends just laughed. Devon is thinking, “Why not? I’m big and strapping” — you know, the typical western thing.

And they said, “Yes, but you cannot feel in your bare feet if there’s an elephant some distance away. And you can’t hear the difference between a baboon and something else. And you won’t know it’s a snake and not a branch in that tree.” That really shifted things for him.

Yes, life-changing for sure. I often hear, “You are so courageous.” I don’t think so. You just go for it when the situation arises. I was more scared of falling off the horse at first, but I put my trust in the Zimbabwean guides and became fearless, really.

Photo by Luc Bataillard

The whole horseback safari was life-changing. The feeling in the body riding 30 kilometers a day, every sight and every sound and every scent, sleeping on the ground, the African night sky above. Electric. There is no return to “normal” after that.

Two things come to mind. First, being with the elephants in a sanctuary in the Cheredzi Conservancy of the lowveld — observing the intelligent familial relations of another species up close puts humans in truer perspective in this grand world.

Photo by Roy Aylward of Wild Walks

Second, an elephant approaching me, as shown in the photo on the back cover of the book. The friend and guide standing behind me whispered, “Can you feel that?”

Yes, of course I can feel it! In my body. The vibration. You feel it in your feet and know in your bones that you and the elephant are on the same ground. Everything is one vibrational field of earthiness. Which is, I imagine, how the traditional Shona are in tune with their world.

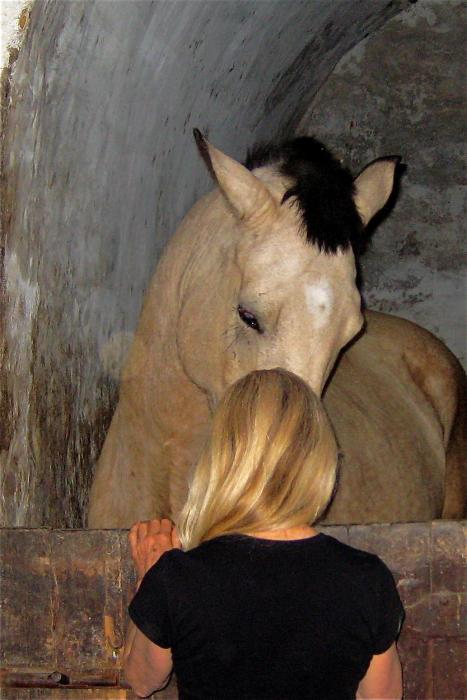

I began the natural horsemanship in 2002. And then trained in Equine Guided Learning in 2004. I came to these things in my early 50s. I was scared of horses before that.

Yes and no. I mean, I had ridden casually, bareback around Cortes Island. But I wanted some new confidence in general at that time in my life, to build new skillfulness, and horses were the way.

I do. It’s series of embodied practices, and I do them regularly. And those have been life-changing as well. In Africa, I think that's what allowed a deep sensibility with the land, the spiritual landscape of the wilderness and the village communities. It was that meditation in that geographical place.

Tami Simon and Sounds True were my introduction in 2008. I would credit these practices and retreats with opening me or attuning me to everything that has happened since. In Zimbabwe I once did a self-retreat in the wilderness with the Sounds True recorded Bodhicitta course. Those heart practices continue to be a most valuable life skill anywhere in the world. Being able to keep one’s heart open, rather than shutting down or feeling overwhelmed in the face of suffering. Compassion. Learning to discern, in a particular situation, whether I can or should take action — or not — to meet a need or lessen a suffering. True for what I encounter in Africa — and everywhere, of course.

This year, I gave copies of The Geography of Belonging to my friends and Shona family who are characters in the story, so they could see the fulfillment of one of my purposes in writing the book:

When I had asked “What I can do as one foreign visitor?” Everyone said, in their own words, “Tell your friends, show the world what the news media does not. That our country is beautiful, our people are happy and generous, our culture is rich and alive. We are proud to be African, Zimbabwean.”

And thank you, Debra, for joining us in that mission with this interview.

What draws me back is the Shona family of Stephen, and the village community, the rhythm of bodies as they move. Ceremonial spiritual life, mbira music, reverence for the Ancestors. And, of course, the pull of the African landscapes, both peopled and wild. Do you know the term petrichor? It’s the scent of rain on the earth.

Photo by Stephen Hambani

More recently I found myself at Healing with Horses Zimbabwe, near Bulawayo. It’s an equine therapy centre, a refuge of love and inclusion for special children who come each week. The two founders and their community of staff/volunteers are absolutely and completely devoted to serving these special kids. I feel privileged to do Equine Guided Learning activities with the horse grooms, with the kids who are able to participate, and with parents, donors and board members.

That’s what takes me back to Zimbabwe, to be of service like that.

Zimbabwe was formerly the breadbasket of southern Africa, but the socio-political-economic climate changed drastically over the past two decades (another story) causing commercial agriculture to disintegrate. Since my first trip there in 2010, the seasonal weather isn’t as predictable, it’s less dependable; as we all know, that’s difficult for farming, both small and large scale. This year it was unusually cold and rainy for the first couple of months I was there, January and February. Like everywhere, there would be certain times of the year for planting, times when one would expect the harvest, whether it's maize or tobacco, and that’s out of kilter.

Something I have seen firsthand is the Soft Foot Alliance, the human-wildlife interface on the land and with the land. Founders Brent Stapelkamp and Laurie Simpson were invited to make their home in a traditional village community. Engaging with their neighbors, researching and collaborating in holistic land and livestock management, permaculture design, fuel-efficient homemade cooking stoves and so on. Being there affirmed my faith in human goodness and generosity of spirit. Really, Zimbabweans are genius at “making a plan,” which actually means improvising as you go along, creating solutions in the midst of ever-changing conditions.

Coincidentally, on a long bus trip, I met a young friend of theirs, Rufaro, who is devoted to her permaculture education project in Gweru. She showed me photos of her abundant crop fields side by side with her neighbor’s sparse ones — to demonstrate to the community and beyond the difference between conventionally grown crops and crops grown using permaculture principles and practices. Rufaro is one of the Soft Foot Alliance Trust team members advocating for regenerative agriculture.

Very specifically, there is a space held for personal, family and community loss. In February, a young friend, a beginning safari guide, took me camping in Mana Pools, a National Heritage Site alongside the Zambezi River. In the night under the stars by the campfire, he told me the story of his three-year-old daughter dying suddenly. All the extended family had immediately gathered from near and far to hold the bereaved in a protective bubble so to speak. For three weeks, neighbors and friends supported and cared for them, allowing space for this necessary human task of grieving. I must say the stars seemed brighter than ever that story-telling night.

I learned that death in Shona culture means joining the Ancestors, our divine predecessors. There is no way around this spiritual reality. As I write in the book, when my mother died while I was in Africa, I was held in that atmosphere while tending to the spiritual rituals of her passing while my sister back in Canada was taking care of the practicalities. Yes, a blessing indeed.

Another way I learned about grieving was from Malidoma Somé [the late healer, writer and teacher from Burkina Faso]. The foundation of his work is grief rituals, creating and allowing space to mourn the losses, as you say both personal and planetary.

Yes, and such a beautiful quote to end with. Thank you, Debra!

Photo by James Varden

All photos by Oriane Lee Johnston unless otherwise credited.

Read Oriane Lee’s previous stories for Voices for Biodiversity, Mozambique Horse Safari and Elephants in the Refuge.