We had traded phone calls all summer, trying to synchronize our schedules. Finally we found a day in mid-August that worked. I drove from Albuquerque the evening before, with a dazzle of desert lightshows on either side of the highway. To the east, a thick and gaudy rainbow arched over mountains; to the west, low, black clouds with staccato bolts of pink lightning pierced through a downpour. The brown landscape turned emerald before my eyes. Rainfall in the dry lands works this way: no precipitation for months, then almost all of the annual ten inches blasts down during the two-month monsoon season. The short bunchgrasses that form the vegetative mantle over the thin soil and volcanic rock of the area are uniquely adapted to this rude life, and all the other species in the surrounding web are dependent on them.

The Aplomado falcons (Falco femoralis) are only one of the many species of birds that claim the grasslands as their habitat, including prairie songbirds, owls, poorwills, doves, hawks, hummingbirds, and quail. Surprisingly, for such a humble biome, grasslands around the world are identified as areas of outstanding biodiversity, home to large and small vertebrates, including birds, amphibians, reptiles, insects, and plants. Almost half of the 234 United Nations-designated Centers of Plant Diversity are grasslands. This falcon release program I had traveled to see was bringing an icon back to the skies, its tapered shadow calling attention both to the hope of re-establishing its proud presence, and the challenges of maintaining its threatened habitat.

The Aplomado falcons (Falco femoralis) are only one of the many species of birds that claim the grasslands as their habitat, including prairie songbirds, owls, poorwills, doves, hawks, hummingbirds, and quail. Surprisingly, for such a humble biome, grasslands around the world are identified as areas of outstanding biodiversity, home to large and small vertebrates, including birds, amphibians, reptiles, insects, and plants. Almost half of the 234 United Nations-designated Centers of Plant Diversity are grasslands. This falcon release program I had traveled to see was bringing an icon back to the skies, its tapered shadow calling attention both to the hope of re-establishing its proud presence, and the challenges of maintaining its threatened habitat.

No one knows for sure what drove away or killed off the Northern Aplomado Falcon in the United States, but in 1986 the raptor was listed by the federal government as an endangered species. The protective designation came a little late – it had been thirty-four years since the last nesting pair had been documented in the Southwest. Once a common sight with its long tail and deep wing beats hovering over an ocean of grass, the elegant, slim-bodied falcon had vanished from New Mexico, Texas and Arizona by the 1950s. This was most likely due to habitat degradation, rampant pesticide use, and other factors related to increasing human impingement on the open range. Not that the raptor was hunted or deliberately extinguished; rather it was a casualty of poor land management practices in an era when the bounty of the earth was still thought to be endless.

.jpg) I had never heard of Nutt. The town turned out to consist of a closed bar, a trailer home that looked deserted, and a rusting tractor leaning over a ditch. Across the county road, abandoned tank cars from a freight train glinted in the sun, the tracks hidden by the overgrowth. In the late 1800s Nutt had been a busy railroad hub between the silver and gold mining towns of Kingston and Lake Valley. Now, the shuttered Middle-of-Nowhere Tavern summed up a period of history that was all but forgotten. The wind lifted paper trash, impaling it on burrs of nearby cholla and creosote bush still smelling faintly of tar leaching after rain. Just when I was surrendering to the utter desolation of this empty crossroads, Angel arrived.

I had never heard of Nutt. The town turned out to consist of a closed bar, a trailer home that looked deserted, and a rusting tractor leaning over a ditch. Across the county road, abandoned tank cars from a freight train glinted in the sun, the tracks hidden by the overgrowth. In the late 1800s Nutt had been a busy railroad hub between the silver and gold mining towns of Kingston and Lake Valley. Now, the shuttered Middle-of-Nowhere Tavern summed up a period of history that was all but forgotten. The wind lifted paper trash, impaling it on burrs of nearby cholla and creosote bush still smelling faintly of tar leaching after rain. Just when I was surrendering to the utter desolation of this empty crossroads, Angel arrived.

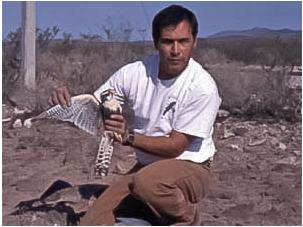

Quick introductions, then I jumped in his truck. The release site we were visiting was a few miles away in the Nutt Grasslands, an open and sprawling patchwork of state and federal lands in Luna County, used by ranchers for cattle grazing. Angel filled me in on the history of The Peregrine Fund while negotiating the muddy two-track leading to the blind where we could watch the falcons. He tossed me an occasional glance as he spoke, his boyish face crinkled with intensity under close-cropped hair.

Dr. Tom Cade, a Cornell-based ornithologist with a passion for raptors, was deeply troubled. By the late '60s, the peregrine falcon was on the verge of extinction in the United States due to widespread use of DDT. This synthetic pesticide was insoluble in water, which made it quite effective against mosquitoes and agricultural pests. Rachel Carson raised the cry identifying this would-be chemical savior as a persistent environmental poison. For the peregrine falcon, it was deadly. The chemical mix of DDT did dissolve in fat, magnifying in toxicity as it accumulated up the food chain to predator species like the falcon. Acting as a hormonal disrupter, the eggs the falcons laid had shells so thin they would burst from the weight of the roosting parent. In 1970, Cade started The Peregrine Fund to try to restore this extraordinary bird, known as the fastest creature in the world. His program accomplished what few thought it could do, releasing captive-bred fledglings to re-establish in the wild.

Dr. Tom Cade, a Cornell-based ornithologist with a passion for raptors, was deeply troubled. By the late '60s, the peregrine falcon was on the verge of extinction in the United States due to widespread use of DDT. This synthetic pesticide was insoluble in water, which made it quite effective against mosquitoes and agricultural pests. Rachel Carson raised the cry identifying this would-be chemical savior as a persistent environmental poison. For the peregrine falcon, it was deadly. The chemical mix of DDT did dissolve in fat, magnifying in toxicity as it accumulated up the food chain to predator species like the falcon. Acting as a hormonal disrupter, the eggs the falcons laid had shells so thin they would burst from the weight of the roosting parent. In 1970, Cade started The Peregrine Fund to try to restore this extraordinary bird, known as the fastest creature in the world. His program accomplished what few thought it could do, releasing captive-bred fledglings to re-establish in the wild.

It was a success story. DDT was banned from use in the United States in 1972. The released falcons multiplied and thrived, and in 2009 the peregrine was removed from the endangered species list. Through the years, the Fund turned to other decimated raptors such as the California Condor, Bald Eagle and Mauritius Kestrel, eventually establishing programs for threatened species on every continent except Antarctica. The birds are bred at the Peregrine Fund's base of operations in Boise, Idaho, and transported across countries and oceans when the birds reach the age they would normally fledge. Through trial and refinement, the Fund has worked to find the best way to re-introduce these young initiates to their native habitats. In 1993, The Peregrine Fund took on Aplomados.

The last nesting pair of Aplomado Falcons was recorded in the Southwest in 1952, taking up residence in the New Mexican town of Deming. Angel grew up there with that ornithological claim to fame already on his radar, but he was astonished to see his first Aplomado hovering over the White Sands Missile Range forty years later. Understanding that fellow biologists would find that hard to believe, Angel got a friend to actually snap a photo as proof. Some time passed until he started working for the Fund, but, he told me, he has had the good fortune to be able to devote eighteen years of his life, so far, to this unique falcon.

We bonded over turtles and toads. At first, Angel was cautious with me, having been somewhat betrayed by the angle a journalist took recently on The Peregrine Fund's projects, and I came to understand the program is not without controversy. My first test was the turtle, which Angel somehow saw camouflaged against the muddy road. We stopped, and since the turtle was nearest to my side, he waited for me to act. I picked it up to move it away, its legs still busily kicking against empty air. When we pulled up to the release site and waited for the monitors to come talk to us, Angel scooped up a horned toad and put it in my hand. I had never looked eye to eye with a dry-skinned toad before. It was cool in my palm before it leaped away.

We bonded over turtles and toads. At first, Angel was cautious with me, having been somewhat betrayed by the angle a journalist took recently on The Peregrine Fund's projects, and I came to understand the program is not without controversy. My first test was the turtle, which Angel somehow saw camouflaged against the muddy road. We stopped, and since the turtle was nearest to my side, he waited for me to act. I picked it up to move it away, its legs still busily kicking against empty air. When we pulled up to the release site and waited for the monitors to come talk to us, Angel scooped up a horned toad and put it in my hand. I had never looked eye to eye with a dry-skinned toad before. It was cool in my palm before it leaped away.

We stood quietly, the sun-splashed grasses fanning all around in a gentle breeze. About five hundred yards away were two falcon 'hacks' on twelve-foot-tall stilts. Searching for the falcons, all I saw were dark shapes huddled toward the back of the nearest structure, mostly obscured. A bare tree limb was attached to one side. A bird leapt to it, and then to the roof. It began to tear its beak into something.

The two young monitors, Cara and Kelly, came over to talk. For six weeks, they spend many hours a day tracking the released fledglings. From 6:30 am to 10:30 am, they supply the first feeding, tying the bodies of dead quail—specially bred for this purpose—to the hack. Before they go for the morning, they retrieve whatever bloody mass is left so it won't attract vultures. Later in the day they return, from 6:00 pm until sundown, for another feeding and record-keeping. Out of eleven birds released in July, three have disappeared, but the rest still return, gradually weaning from the provided food to their own kills. Perhaps the three missing falcons got lost, or were killed by the great horned owl that preys on them. Eventually they all leave, spreading out over the landscape to establish their own territories.

I was prepared to have my breath taken away when I saw the falcons for the first time. "Aplomado" is Spanish for "lead," describing the blue-gray plumage of the falcon's back. But it is the other markings that give this raptor its remarkable beauty: a Zorro-like mask of dark feathers around darting eyes, a black teardrop dipping to the white smock of its breast, and cinnamon-colored belly and legs. Its jail-house tail and wings are banded with white, gray and black stripes which seem to ripple as it flies. The glimpse I caught of the fledglings through the binoculars was a little disappointing as they were still wearing their adolescent brown grunge. They could have been any raptor, but there was no mistaking them once they took flight. And they had definite personalities, the girls told me. C4 was always the first one in for breakfast, D8 was bossy, and another one was always complaining.

This year, sixty-seven fledglings were released in southern New Mexico and forty-one in West Texas. The first release program in South Texas has been discontinued, except for intermittent monitoring, with thirty-seven nesting pairs successfully established there since the 1990s. Since the program began in New Mexico on Ted Turner's Armendaris Ranch in 2006, hundreds have been released, but so far only about eleven pairs have set up house. When sixty nesting pairs of Aplomados throughout the Southwest show continuity over time, this program too will end. The numbers sound so few, but Angel assures me that is what the remaining habitat can sustain.

.jpg) With deceptively simpler structure than other biomes but incredibly rich in biodiversity, grasslands throughout the world are threatened by a combination of factors. The greatest impact is from increasing conversion of grasslands to agriculture and urbanization; also energy development, fragmentation by roads, and the onslaught of invasive species replacing native plants. The result of these is loss of the health of the grasslands and their ability to provide habitat for game species, grazing herbivores, medicinal plants, and the genetic materials necessary to breed varieties of cereal crops that will be resistant to disease. Other critical functions that grasslands perform include protecting fragile soil from wind and water erosion, and acting as vast carbon sinks for greenhouse gas sequestration. One of the first indicators of terrestrial ecosystem decline is the loss of biodiversity. The North American Bird Survey has noted that over the past twenty years, grassland birds have shown the greatest decline of any group in the survey. In the same period, Black-tailed Prairie Dogs, a keystone species for the health of the ecosystem, have been reduced by 73 percent. Little attention has been paid until now on the quantitative indicators of grassland condition, but recently, scientific organizations such as the World Conservation Union and the World Resources Institute are focusing studies on one of the planet's greatest life support systems.

With deceptively simpler structure than other biomes but incredibly rich in biodiversity, grasslands throughout the world are threatened by a combination of factors. The greatest impact is from increasing conversion of grasslands to agriculture and urbanization; also energy development, fragmentation by roads, and the onslaught of invasive species replacing native plants. The result of these is loss of the health of the grasslands and their ability to provide habitat for game species, grazing herbivores, medicinal plants, and the genetic materials necessary to breed varieties of cereal crops that will be resistant to disease. Other critical functions that grasslands perform include protecting fragile soil from wind and water erosion, and acting as vast carbon sinks for greenhouse gas sequestration. One of the first indicators of terrestrial ecosystem decline is the loss of biodiversity. The North American Bird Survey has noted that over the past twenty years, grassland birds have shown the greatest decline of any group in the survey. In the same period, Black-tailed Prairie Dogs, a keystone species for the health of the ecosystem, have been reduced by 73 percent. Little attention has been paid until now on the quantitative indicators of grassland condition, but recently, scientific organizations such as the World Conservation Union and the World Resources Institute are focusing studies on one of the planet's greatest life support systems.

Angel Montoya witnessed firsthand the intense pressure on grasslands to convert them to food production. As a graduate student still enthralled with his sighting of the Aplomado on the missile range, he crossed the border to Mexico in search of the rare falcon. Thought to be extinct throughout the whole Chihuahuan Desert, Angel listened to the stories of the local ranchers, eventually tracking down forty nesting pairs in the Tarabillas Valley. This find gave hope to the possible recovery of the northern subspecies, this desert-dwelling Aplomado, to the land where it had vanished. The Peregrine Fund removed some young falcons from nests in other parts of Mexico and the Yucatan, bred them in captivity, and used their hatchlings for the releases in the United States.

Once the water is exhausted, the farmers will need to move on. It is unlikely that the native grasses will return. As in the Great Plains desertification, the broken soil will blow away and woody shrubs that flourish on disturbed land will take root. The falcons will already be gone, never to be seen there again, their preferred prey seeking other areas for their migratory roosts.

Although grasslands are fully one-quarter of the earth's total land surface, less than 1 percent of the world's grasslands are protected. They are shrinking at an estimated 5 to 10 percent a year, from the Great Basin in North America, to the steppes of Eastern Europe and Asia, the pampas of Argentina, and the South African veld. Roughly 1.5 billion people depend on grasslands for their livelihoods, a number that will only keep growing. The American West barely holds the memory of the vast grasslands spreading from the Dakotas to Texas. It took only fifteen years after the Homestead Act of 1862 to irrevocably change the ecosystem. Now, apart from urban areas and farmland, it is mainly Big Sage country, barren with desolate spaces in between shrubs, or filled with noxious weeds and cheatgrass.

Keeh, keeh, keeh I hear the sharp cries of the young falcons as Angel and I walk to the truck. The melodious voices of songbirds too, which Angel identifies as horned lark and purple martin. "Falcon food," he says and smiles, then expresses another concern. The Nutt grasslands are being evaluated for wind energy development, a ridge nearby slated for installation of twenty-eight turbines. The Macho Springs Energy Project, a subsidiary of Element Power, is scheduled to break ground in December 2010. At that time, this release site will be abandoned. There is high bird and raptor mortality associated with turbines, and Angel is worried about his Aplomados. Even though the falcon is listed as an endangered species, that is not enough to halt the inalterable impact of energy development on this habitat. Some prefer it that way, others are angry, and Angel is clearly in the middle.

.jpg) In order to facilitate the Aplomado release program, the Department of the Interior gave the particular released individuals an unusual status. They were deemed under section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act to be "non-essential experimental populations." The substance of this distinction gave the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) flexibility in introducing the falcons into their historical range without the tangle of restrictions that a straightforward endangered species designation would entail. The philosophy behind this slicing of words was that it allowed current land practices to continue and encouraged the participation of ranchers in supporting the releases. The ranchers were comfortable that if a released falcon was accidentally killed on their property, they would not be liable for fines. In Texas, with almost all the land owned privately, it was called The Safe Harbor Cooperative Agreement, and generated no controversy.

In order to facilitate the Aplomado release program, the Department of the Interior gave the particular released individuals an unusual status. They were deemed under section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act to be "non-essential experimental populations." The substance of this distinction gave the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) flexibility in introducing the falcons into their historical range without the tangle of restrictions that a straightforward endangered species designation would entail. The philosophy behind this slicing of words was that it allowed current land practices to continue and encouraged the participation of ranchers in supporting the releases. The ranchers were comfortable that if a released falcon was accidentally killed on their property, they would not be liable for fines. In Texas, with almost all the land owned privately, it was called The Safe Harbor Cooperative Agreement, and generated no controversy.

This designation, Angel said repeatedly, "was only a tool," used by The Peregrine Fund to protect landowners and at the same time, provide the falcons with high-quality habitat. The conservation organization Forest Guardians, now called WildEarth Guardians, did not agree. They asserted that sighting of a nesting pair of wild, unbanded Aplomados in Luna County, NM, in 2002 proved that there were naturally occurring populations that deserved the full protection of the ESA. Forest Guardians petitioned the FWS to designate Critical Habitat for the endangered species in New Mexico, Arizona and Texas. When the FWS did not respond, they sued. A lower court found in favor of the FWS; the Forest Guardians appealed, and this summer a three-Judge Panel decision from the Tenth Circuit Court found in favor of the "inessential" designation, meaning that the released falcons were not critical to the survival of the species. Whether the agency or the conservation group held the moral high ground might still be in debate, but, unquestionably, there are more Aplomado falcons in the Southwest now then there has been for a century.

About a hundred miles east of the release site I visited is another grassland in New Mexico, where the Aplomado are beginning to establish. The 1.2 million acres of Otero Mesa are the most pristine and the largest intact swath of the vanishing Chihuahuan desert grassland ecosystem. Unlike the Nutt region, which is dominated by tobosa and side oats grasses, Otero Mesa is a remnant black grama grassland, truly a living relic of New Mexico's past. Black grama is the predominant grass, but other species include blue grama, alkali sakaton, burrograss, dropseeds, ring muhly and fluffgrass. More than one thousand native species inhabit the vast area including mule deer, kit fox, the endangered black-tailed prairie dog, mountain lion, gold and bald eagles, and the most genetically pure herd of antelope in he state. The Audubon Society lists more than two hundred birds that breed or use the habitat on their migratory routes, including several threatened species. Thousands of inscribed petroglyphs and the ruins of a station on the old Butterfield Trail show the passage of human history, but grazing was kept under control, and the land retained its untouched beauty and biodiversity. In 2005, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) opened Otero Mesa to oil and gas exploration, even though years earlier the Harvey Yates well produced little and was shut down. However, recent technologies seemed to show the presence of natural gas reserves, and environmental organizations challenged the BLM's management plan that did not equally consider giving permanent protection to this unique and ecologically critical grassland.

About a hundred miles east of the release site I visited is another grassland in New Mexico, where the Aplomado are beginning to establish. The 1.2 million acres of Otero Mesa are the most pristine and the largest intact swath of the vanishing Chihuahuan desert grassland ecosystem. Unlike the Nutt region, which is dominated by tobosa and side oats grasses, Otero Mesa is a remnant black grama grassland, truly a living relic of New Mexico's past. Black grama is the predominant grass, but other species include blue grama, alkali sakaton, burrograss, dropseeds, ring muhly and fluffgrass. More than one thousand native species inhabit the vast area including mule deer, kit fox, the endangered black-tailed prairie dog, mountain lion, gold and bald eagles, and the most genetically pure herd of antelope in he state. The Audubon Society lists more than two hundred birds that breed or use the habitat on their migratory routes, including several threatened species. Thousands of inscribed petroglyphs and the ruins of a station on the old Butterfield Trail show the passage of human history, but grazing was kept under control, and the land retained its untouched beauty and biodiversity. In 2005, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) opened Otero Mesa to oil and gas exploration, even though years earlier the Harvey Yates well produced little and was shut down. However, recent technologies seemed to show the presence of natural gas reserves, and environmental organizations challenged the BLM's management plan that did not equally consider giving permanent protection to this unique and ecologically critical grassland.

In this case, the environmental groups won: Otero was granted a temporary stay on energy development and the BLM sent back to reframe their management alternatives. Right now there is a groundswell from the surrounding communities, as well as state-wide, to give this incredible landscape the permanent protection it deserves. Otero Mesa is on the short list for designation as a national monument, giving New Mexicans a chance to hold on to an area that evokes the past and also the future, the possibility of protecting the areas that are the lungs and heart of the biosphere.

The real richness is in the experience of it. Scientific concepts about biodiversity, climate change, habitat degradation, and species extinction are abstract, though so vitally important. But they fall somewhere behind the experience. In Otero Mesa, there is a sublime openness, a quietude that the urban dweller can easily forget exists. The early autumn grasses are metallic sprays shimmering in sunlight; a hawk cries; a pronghorn buck freezes before he moves on. For the mystically inclined, I might say that an intact grassland has a very full emptiness. You are completely at attention, expecting something to happen, even if that is just a horned toad studying you with half-closed eyes, or a young Aplomado falcon soaring in play.

Coda

As a coda, I want to dedicate this to Manny. In my research about falcons, species extinctions, and bird mortality rates, I came upon an article in the Spring 2001 issue of Orion Magazine. In it, the writer was exploring the biodiversity that managed to thrive on lower Manhattan Island: sea turtles washing into the harbor, peregrine falcons nesting in the Financial District, the thousands of migrating birds using the skyscraper breezes for their flyway. But it was the death and injury of smaller birds, crashing into their own reflections on the glassy walls of buildings, which really caught her interest. Manny was a security guard at the World Trade Center. The writer made no note of his last name, but she wrote of his distress at the number of birds who died there. He would gather the bodies of the dead and bring them to a bird watch volunteer, or gently hand over the stunned and injured birds in the hope they would be cared for.

I don't know if Manny lived or died later that year, but when I read that Orion article, I felt so deeply the pang of loss. No one is untouched by the enormous tragedy that took place in a single day in September 2001. The loss of biodiversity is not as traumatic or quick, but it does leave a hole. For me this little story about Manny evoked how irrevocable is great loss, and the potential for small human acts to make a difference.

Statement from Peregrine Fund

Statement from Peregrine Fund

The Peregrine Fund was founded in 1970 to restore the Peregrine Falcon, which was removed from the U.S. Endangered Species List in 1999. That success encouraged the organization to expand its focus and apply its experience and understanding to raptor conservation efforts on behalf of 102 species in sixty-four countries worldwide, including the California Condor and Aplomado Falcon in the United States.

Photos are copyright protected and are used by permission. Photographs may not be reproduced without permission. Copyright information for the photos is as follows: (1) Angel Montoya, photo courtesy of Angel Montoya, (2) Pronghorn antelope, photo courtesy of Angel Montoya, (3) Aplomado Falcon, photo courtesy of Chris N. Parish, (4) Grasslands, photo courtesy of Zoe Krasney, (5) Aplomado Falcon fledglings, photo courtesy of Angel Montoya, (6) Hack box, photo courtesy of Zoe Krasney, (7) Aplomado Falcon, photo courtesy of Chris N. Parish, (8)Tractor, photo courtesy of Gil Sorg, (9) Grasslands, yucca and cornudas, photo courtesy of Nathan Newcomer, (10) Otera Mesa, photo courtesy of Chris N. Parish

https://plus.google.com/114205602050164572686/posts