Blue whales can be found in the North and South Atlantic Oceans. Generally blue whales grow to an average of 25-27 meters in length,, and communicate with each other via low frequency whistles. Many blue whale groups migrate to the poles annually.

Sri Lankan blue whales differ from the norm in several ways. Sri Lankan blue whales tend to be much smaller. The longest recorded specimen measured was only 25 meters long. The whales found in Sri Lankan waters have calls that are acoustically unique from those used by other blue whale populations. However, the biggest difference is that these blue whales don’t migrate to polar waters. Some reside in the Sri Lankan waters year round.

Ironically, growing interest in these whales and a resulting increase in whale-watching tourism may be contributing to their decline. Some scientists believe that the increase in whale watching could be forcing whales to seek food farther from their normal territory, and into the shipping lanes.

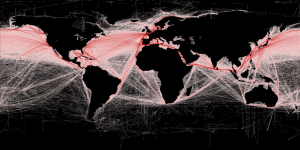

Experts think the rise in unregulated whale-watching boats contributed to the unprecedented number of whales struck and killed by ships last year. A reported twenty whale carcasses (not all belonging to blue whales) were seen around the island last year. But researchers say the number of blue whales struck could be ten to twenty times more – since blue whales often sink soon after they are struck.

Asha de Vos, a marine biologist and Sri Lanka native, has spent the past three years researching this unique population. She hopes her research will convince the government to shift shipping lanes further out to sea, and ultimately provide guidelines and regulations for the whale-watching industry. Many other countries have laws that prohibit getting too close to blue whales on whale-watching trips. Ms. de Vos would like to see similar regulations in Sri Lanka.

Although she recognizes that whale watching is a critical for the economic development her ountry, Ms. de Vos believes this increase in tourism may be happening to0 fast. “Right now, whale-watching boats are driving helter-skelter around the animals,” she said in a recent interview with the New York Times. “I don’t want it to explode into something that becomes harassment for the whales.”

In addition to promoting proper regulations for the whales, Asha continues to do research to help learn more about Sri Lanka’s blue whale population. Asha and team of researchers from the Duke University Marine Lab are currently crisscrossing Sri Lankan waters with the goal of better understanding the habits and characteristics of this Blue Whale population and why they choose to live in those waters. It is their hope that with this understanding higher level of protection for the species will follow.

“In this new era of peace, the blue whale is very fast becoming a symbol of our country,” says Asha, “it would be very sad to harm these animals because of our foolishness.”

Saving Blue Whales (Video)

Learn more about Asha de Vos and her efforts:

Protecting the Enigmatic Blue Whales of Sri Lanka: In Conversation with Asha de Vos

Learn more about the Blue Whale:

Photos courtesy of Mike Baird, Morro Bay, USA and Wikimedia Commons and created by Grolltech