Quammen estimates that all large predators will be extinct by the year 2150 due to human exploitation of these animals and their habitat. In an effort to understand what has driven people to exploit predators, Quammen explores what he calls “the fear of being meat” while questioning just how deep this fear runs in the human psyche. During a powerful visit to the Chauvet Cave in France, where some of the cave paintings are said to be thirty-five thousand years old, one scene depicts a pride of maneless lions in a beautiful, thoughtful, discerning manner, leading one to wonder whether or not our primal instincts were always hard-wired to eradicate predators for human safety or whether we sensed more in our possible human connection to other species. Some of our ancestors found beauty, maybe even purpose, in these beastly beings, showing us that there is an element of human choice in our relationships with predators.

One aspect of the book I found problematic was the substantial absence of a female perspective – not one of Quammen’s principal interviewees was a woman. His informants were mainly hunters and male heads of the household. In many places around the world, women work close to the land via farming or gathering water in order to care for their families. It is not uncommon for women to be the first ones in the community to experience the adverse effects of poor resource management decisions, mainly degradation of land and water quality and quantity, which are often made by male leaders living in a different part of the country. This creates a disconnection between the decision-makers and the people who experience the effects of such decisions. Quammen’s failure to include women more prominently in his book further perpetuates the marginalization of women in resource management decision-making, which is a global loss.

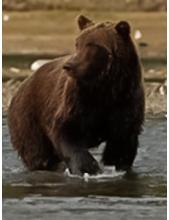

Photos are copyright protected and may not be reproduced without permission. Copyright information for the photos are as follows: (1) Tiger and Man, photo courtesy of Zhou Minyun (2) Crocodile, photo courtesy of Aldolpholazo (3) Grizzly, photo courtesy of Brenda Phillips (4) Bio photo, photo courtesy ofJami Wright .