Read Part 1 of this beautiful tale here.

Whenever there is work requiring strength or courage, people ask, “Are there no warriors around today?” He also told me from his own experience as a warrior how self-confidence and pride take over one’s whole being. There is a feeling of ease, as if you and those around you are thinking, “Everything will be alright as long as Maasai warriors are here.” He said they were brave, brilliant, great lovers, fearless, athletic, arrogant, wise, clever, and, above all, concerned with the protection of their comrades and of the Maasai community as a whole. He said:

A lion would roar near our kraal at night, and we would be so insulted at his boldness. All we would wish for was daybreak so that we might go in search of the lion, hunt him and teach him a lesson. We warriors, and not he, reign supreme! We used to say that until a lion could roast his meat – that is, stop eating raw meat – he would never be able to challenge us. We used to boast that although a lion could run faster than we could, we could run further, afraid of nothing short of almighty God.

Even foreigners don’t scare warriors, and often they don’t bother to distinguish persons, white or black, dressed in foreign clothes. They sum up them all up with the word ilmeek, meaning “aliens,” or ilorida enjekat, meaning “those who confine their parts,” referring to the nature of European clothes, which, unlike the Maasai toga, do not allow the wind to blow away unwanted odors! He told me that the arrogance of the warriors is so obvious at times, though they generally respect their elders and respond to their wishes, so I should also listen to what he was about to tell me.

He said that I should take the cattle into the forest because the drought was becoming worse every day. I respected his opinion, and the following day, I left with an older relative and traveled into the forest with 101 head of cattle. We lived inside the forest for four full months, and still it didn’t rain. All the grass dried up, and our livestock began to feed on tree leaves. In the forest, we survived on their milk and meat. We had no matches; instead we used sticks of the fig tree, Ficus thonningii, as a fire starter. Indeed, we depended on the forest for our existence and our livelihood. I remember when I became sick with malaria; we prepared a liquid cure from the roots of the Rhamnus prinoldes tree. I drank a cup of it every day, and after three days, believe me or not, I was healed.

After a long time in the forest, it rained, and we went home with the cattle that had survived. Forty-three of our herd had died of hunger, but if it weren’t for the forest, we would have lost them all.

Rain is revered in Loita. The land district as a whole has a semi-arid climate with between 500-700 mm of rainfall per annum, while the forest receives about 1250 mm. My people, the Loita Maasai, understand the role that the forest plays as a water catchment area, as all water sources in Loita emanate from the forest. The forest is very important as a drought and dry season safety net. Although the pasture in the forest is good year round, community members resist the temptation to graze there, instead using traditional wet and dry season grazing areas.

Our livelihoods depend on the goods and services provided by the forest. The reverence we attach to the land and the respect we bestow upon the laibon, or traditional custodian of the forest, have been key factors in the continued responsibilities felt by my community toward the conservation of this land. Any decision that affects the integrity of the forest impacts the basis of our way of life. The strong spiritual and cultural relationship between my community and the land is well exemplified by our many traditional songs, proverbs, sayings and myths. Many ceremonies essential to our culture are performed within or at the edge of the sacred forest. The current great Maasai laibon is a relative of mine. He belongs to my lineage, Inkidong, and he is charged with the protection and preservation of the Naimina Enkiyio, a responsibility that is passed on from one laibon to the next.

To follow in the footsteps of the laibon, I joined Olchekut Supat Apostolic Secondary School in 2007 and studied there for four years. My work there changed my understanding of the forest and its plants and animals in many ways. I learned that with the growing human population and the pressure for resources, the increased harvesting and inappropriate utilization of natural resources would ultimately lead to depletion and environmental degradation. I began to see that some valuable tree species, used for construction and fencing, are becoming increasingly scarce at the forest edge, forcing community members to go deeper into the forest to harvest them. I saw, too, that recent agricultural development was spreading, leading to conflict with elephants and other animals.

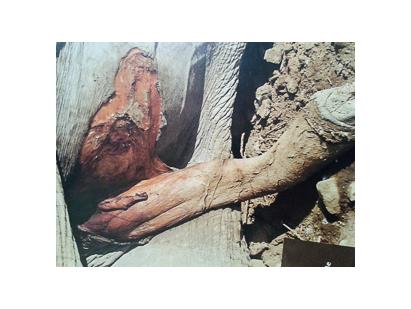

In 2008, I found a carcass of a male elephant with its genitalia hacked off. The motivation of the poachers is still unclear, but witchcraft, strange foreign tastes or the exoticism of owning this type of skin are possibilities. There are still elephants living in the forest, but illegal killing threatens to cause their local extinction if not immediately curbed. Elaborate studies are required to determine the size and status of the population as well as the elephants’ habitat use and movement patterns. Furthermore, it is crucial to determine the corridors used by elephants to move between the forest and the town of Magadi on the Rift Valley floor to the east and Maasai Mara to the west, and to secure their continued movement before these crucial corridors are cut off by settlement.

Due to the biological diversity of this forest ecosystem and the increase in human threats, there is an urgent need to put a conservation emphasis on this area, at both the national and international levels. Naimina Enkiyio Forest and its surroundings form a critical dispersal area for wildlife populations from the Maasai Mara National Reserve and, hence, is key to the conservation of the many species in the Mara region. Furthermore, Kenya’s forests are decreasing at an alarming rate, and every effort must be made to secure the Naimina Enkiyio, both for the sake of protecting biodiversity and for the survival of my people.

In the beginning of May 2013, I volunteered for an organization called ElephantVoices to collect data on elephant signs, sightings and mortalities using ElephantVoices' cell-phone based application, the Mara EleApp, and their online Mara elephants Who's Who and Whereabouts databases. I walked in the forest almost every day looking for elephants. I found the forest to be mostly intact, most mature trees draped with lengthy strands of Spanish moss and lichens and forested hills dotted with several streams draining to the east and northeast. While none of these small waterways are substantial enough to be called rivers, they still appear to be permanent and continue to provide essential water to communities living below the escarpment to the east. During my internship, I had the opportunity to visit Olkiramatian Conservancy, which is below the forest at the base of the Rift Valley’s Nguruman escarpment. It is a very dry and very hot place bisected by the life-giving Ewaso-Ng’iro River, which has its source in the Mau Forest. The river is joined by the Olasur River, which begins at the Oloieni Springs deep in the heart of the Naimina Enkiyio Forest, not far from my home. The Olasur plunges over the Nguruman escarpment, forming a forested corridor that is used by elephants and other animals to move up and down the escarpment. After joining the Ewaso-Ng’iro, the rivers empty into the Ewaso-Ng’iro Swamp, immediately to the north of Lake Natron, in Tanzania, whose pink color can be seen from space. Ranging in altitude from a high of more than 2,300 m in the forest down to 600 m on the Rift Valley floor, this area is extremely biodiverse and ecologically important.

Although wildlife in the Naimina Enkiyio Forest still appears to exist, the animals are shy. In comparison to other protected areas, it’s difficult to see large mammals such as elephants, buffalo and leopards. In July 2013, I had the privilege (while representing ElephantVoices) to join a group from South Rift Association of Land Owners (SORALO) and Africa Conservation Center (ACC) to conduct a wildlife survey in Loita. I interviewed 30 people from different areas around the forest regarding their sightings of lions and elephants, as well as their attitudes toward these animals and the forest. A majority of those surveyed were unhappy about the poaching of elephants and wanted action taken to halt their decline.

I realized through this survey that lions are heading for extinction in the forest – they were last sighted almost 10 years ago – but our survey suggested that leopards may, in fact, be rather numerous. Ungulates commonly encountered include zebra, Coke’s hartebeast, impala and bushbuck. Monkeys are well represented and include baboons, vervet and colobus monkeys, and greater galagos and tree hyrax are very evident from their screams at night.

I am very proud of my work and happy that despite the severe poaching for ivory, I did meet some live elephants. I saw several groups in the forest and a fair amount of fresh signs (fresh dung, fresh foraging, fresh footprints, fresh rubbing on the trees and the strong smell of elephants), which indicate that elephants still exist in the Naimina Enkiyio.

Poaching pressure in the forest is very high, and between the months of May and July 2013, I personally witnessed three dead elephants killed by poachers at Esupukial in the Olorte area. It is beyond my comprehension why these poachers are so very cruel and heartless. I find it deplorable. My heart breaks just knowing of the malicious crimes committed against these elephants and that nothing is being done to save the remaining elephants in the forest. Increased anti-poaching efforts and better land use planning are both required if we are to sustain this elephant landscape.

Naimina Enkiyio Forest is a beautiful place.

Elephants are very precious creatures, and they are actually very important to my country, to my community and to me. They play a number of key roles in the forest. They are able to smell water that is close to the surface of the ground and dig small water holes using their tusks, on which livestock and other wild animals rely during the dry season. In Loita, I have seen wooded areas that were impassable until elephants, through their feeding and with their large bodies, helped to create trails through the thick vegetation. Elephant dung also disperses the seeds of plants and provides a place for them to germinate while also offering nutrition to insects, birds and even baboons and other animals. They are responsible for keeping the forest diverse and by moving plants up and down the escarpment and to the Maasai Mara; they maintain the connectivity of these landscapes. They are also the largest land mammals alive today. The huge animals are a wonder to look at, and this can be profitable to my country’s economy through tourism, one of the fastest-growing sectors in the world.

The Naimina Enkiyio Forest is very useful in the life of my community in so many ways. In rediscovering our forest during my recent work, I visited many different places. I happened to walk through Emowso Oltiyani, one of the view points of the forest, from which there is a magnificent view of the Great Rift Valley, Lake Magadi, Lake Natron, Mt. Kilimanjaro, Maasai Mara, Serengeti Plains, Ngorongoro Crater, Oldonyo Lenkai (an active volcano called “the mountain of God”), Shompole Hills, Ngong Hills, as well as the nearby forest canopy and a swamp hidden in the forest. Imagine seeing all these internationally known places from one spot! The meeting of all these varied landscapes creates a rich visual experience, and the site’s elevation offers magnificent views of these diverse attractions. Close by, a trail to a waterfall lures one back to keep exploring into this lovely, biodiverse forest.

Photos are copyright protected and may not be used without permission. All photos are courtesy of Alfred Mepukori.Photos are copyright protected and may not be used without permission. All photos are courtesy of Alfred Mepukori.