It’s obvious that something is very wrong with the land before our plane even lands in Fort Yukon, Alaska, known to its indigenous Gwich’in inhabitants as Gwich’in Zhee. Even if I had not been to the Gwich’in Gathering in 1998, I’m sure I would still notice the bathtub rings around the lakes, the sloughs and channels that no longer connect, and the sand bar islands in the mighty Yukon River.

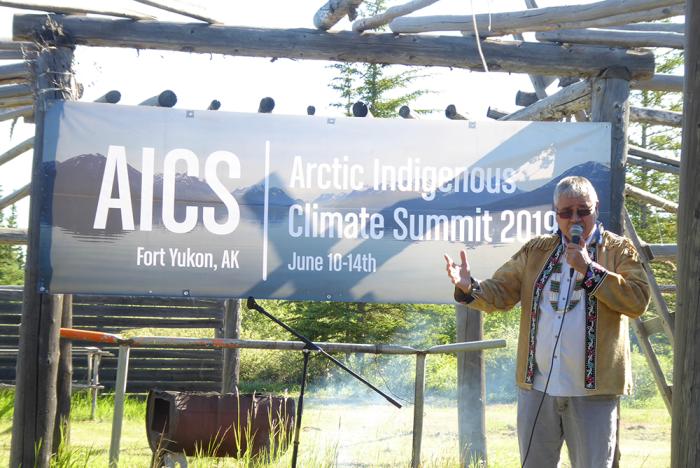

I’m here to attend the Arctic Indigenous Climate Summit, sponsored by the Gwich’in Steering Committee. A couple of months ago, during a phone interview with Executive Director Bernadette Demientieff, I was invited to join a number of journalists, environmentalists and Native activists at the summit June 11–13. I’m covering the same story I did in the mid-90s — the Gwich’in People’s struggle against threatened oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). The Refuge’s coastal plain is held sacred as the birthing grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd that sustains the lives, culture, subsistence economy and spirit of the Gwich’in People. Named for the Porcupine River, this herd of caribou migrates across vast distances in Alaska and Canada, returning to ANWR each year for calving.

Although I’m excited to return 21 years later and the Gwich’in People are as welcoming as they were a generation ago, I can’t completely shake off my heavy heartedness. How is it that after fighting against drilling since the committee was formed to represent the Gwich’in People in 1988, the possibility is now closer than ever? Drilling was off limits until the end of 2017, when a rider to the controversial Republican tax bill sneaked in a provision that called for drilling in ANWR. The current administration seems intent on rushing through all the required environmental reviews, so far without sufficient notice to the Gwich’in, and wants to hold a lease auction as soon as this autumn.

The night before I left my home in New Mexico for Alaska, my hand hit a stack of old cassette tapes in a cupboard. One went skidding down the hall. Incredibly, it was an interview from 1996 of Sarah James, former Executive Director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee. As I listened to the interview, I was shocked that the Arctic Refuge is in more danger now than ever before. I could ask the exact same question — “Why is it that the Republicans in Congress are so intent on drilling the last 150 miles of pristine coastline in the entire country?” — and receive the same answer from Sarah or any number of Gwich’in People and their numerous supporters: “Greed.”

As I listened to the interview — in which I mention that I didn’t have email yet — I wondered what I would find upon my return to Fort Yukon, once again during the midnight sun near the summer solstice.

As I set up my tent in the grassy campsite amongst wild roses and lupine near the outdoor Octagon where most conference activities will take place, I can feel the dryness of the land. Unlike some areas in Alaska — which, like other parts of the Arctic, is warming at twice the rate of temperate regions — the river here is low. In other places, early snowmelt is swelling the rivers. Here the river drifts lazily, and remains an important connection — along the tributary Porcupine River to the portion of the Gwich’in Nation who are Canadian citizens, upriver to the town of Circle where a road leads to Fairbanks, and downriver toward the delta that leads into the Bering Sea.

There are approximately 9,000 Gwich’in People in 15 communities in Alaska and Canada. As Sarah James told me in 1996, “they all depend on the Porcupine Caribou Herd.” The heart of the matter is that the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge, though far from the land where the Gwich’in actually live, is the birthing grounds of the herd, a true wildlife refuge. “Any animal’s birthplace is a sacred place,” Sarah told me long ago. And many other animals give birth there as well. Ducks and other birds nest, and polar bears have their dens. In fact, the Gwich’in name for the coastal plain is Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit — “The Sacred Place Where Life Begins.”

The Gwich’in are known as the Caribou People. They have been hunting and living in this region for 20,000 years — or, as Sarah said, “since time began.” I learned from Bernadette that the struggle against drilling, though still centered around the ability of the Gwich’in People to continue their ancient way of life, now has the added dimension of ensuring food security in a time of climate crisis.

Over the next three days, we hear from Elders, young hunters of the next generation, Gwich’in activists, Native activists from a variety of Indigenous nations, and environmentalists, lawyers, and scientists from all over Alaska and the Lower 48. I’m gratified to see that the Gwich’in — and the caribou — have a lot more support and publicity than they did in the late 90s, before the internet became all-pervasive.

Part of me mourns the simpler, lost world into which I will get glimpses over the next few days — a timeless world of cycles and seasons and living close to the Earth. But don’t think the Gwich’in aren’t adaptable. Teens stop in front of the high school by the carload to use the school’s internet off-hours to check Instagram. Under Bernadette’s leadership, the Gwich’in Steering Committee has a strong online and social media presence. This networking has helped its members to assertively spearhead testimony before Congress, interviews with US and worldwide media and NGOs, and attendance by Gwich’in representatives — including Bernadette herself, who has an exhausting travel schedule — at shareholder meetings of fossil fuel companies from Houston to Denver to Aberdeen, Scotland.

The stakes have never been higher. Two decades ago, the Gwich’in were fighting for their culture and their subsistence, as well as for keeping a small portion of the Earth — about 5 percent of the Alaska coastline — pristine and free from oil and gas development. Only 21 years ago, climate change didn’t come up once in my previous visit’s interviews. Today the climate crisis and attendant biodiversity crisis are twin demons threatening the well-being and food security of not only of the Gwich’in, but potentially all life on the planet.

When I talked to Bernadette on the phone, she spoke about how fast the climate is changing in her homeland. Cycles are off, animals and birds migrate early, “caribou and moose are falling through the ice and drowning,” and strange growths that no one has ever seen have been found in the meat of caribou and salmon.

In Fort Yukon, the first person I reconnect with is Princess Daazhraii Johnson, who was a college student when I met her in 1998. I’ve followed her career through mutual Facebook friends, and am excited that she is Creative Producer of the PBS children’s show Molly of Denali, about an Alaska Native girl and her family and friends. There is a special preview of a couple of episodes for conference guests, and the catchy theme song, sung by my longtime Alaska Native and Greenland Inuit friends from the band Pamyua, is running through my head as she and I sit on the front steps of the tribal hall to have a catch-up.

Princess is Neet’saii Gwich’in from Arctic Village, but spent part of her childhood in Fort Yukon. Just like the idealistic and dynamic young woman I met two decades ago, she is utterly committed to the fight to save the Refuge, and is a former Executive Director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee. When I ask what the slogan “Defend the Sacred” means to her, she says “it’s for all of us on the planet, for all the future generations.” Through her work in film and other media, she is determined to “share the Indigenous world view and make sure those values integral to ensuring future life on the planet are getting out there.” For Princess, the commonalities of Indigenous world views from a vast spectrum across the planet are “a sense of reciprocity and not putting human beings above other life.”

Like many Gwich’in and other Alaska Natives of all ages we will hear from in the next days, Princess describes the early warm-ups that the Arctic is experiencing. Record-breaking warmth in February and March of this year caused snow to melt and then form ice. Unseasonable rain on top of the ice froze again and created a nearly impenetrable surface, preventing the wildlife on which the Gwich’in depend from accessing their normal foods. Princess also expresses a concern about an increase in animal attacks on humans. “Their spirit is upset,” she says. “They are confused right now.”

That “night” I sleep restlessly in the midnight sun. I’m wide awake for a long time, walking by the Yukon River and taking photos of river and wildflowers until I’m finally tired enough to sleep even though it’s light.

The conference begins the next “morning” with a blessing by Navajo Elder and environmental protector Louise Benally from Big Mountain, Arizona. Louise honors the Four Directions and Four Elements in a sacred beginning ceremony using mountain tobacco, an eagle feather, a clay bowl of water, and corn husks. She speaks of the prophecy her grandfather passed on to her: that “one day we will see each other again, the Dineh of the north and south.” There would be a reason for this meeting of Athabascan Peoples, she says, and she believes it is “the climate crisis. We’re endangered because of a few greedy people with no consciousness of honoring the Earth.” She concludes with, “Let us find ways to help each other.” You can watch the interview with Louise here.

Traditional Chief Trimble Gilbert welcomes us to Gwich’in Zhee, the Yukon Flats. “We’ve lived off the land for thousands of years, and now the weather is affecting our way of life.” He speaks of dried-up lakes — the ones I saw from the air — where they used to go to get muskrats, and how they can’t paddle from channel to channel because the river is getting more and more shallow. “People call it subsistence, but that doesn’t describe our way of life, it’s just some word,” he says.

Person after person will talk about how much the land has changed, here and in other areas of Alaska, and not all are Elders looking back decades. Bernadette talks about how much she loves this land and her people. But there are islands in the river that were not there in her childhood or youth. “It’s as beautiful as ever, but it’s different.”

Darrel Vent Sr., from Huslia on the Koyukuk River, a Yukon tributary far to the west, explains how extractive activities have affected the animals in his homeland. The caribou have moved away because of the pipeline, and the paths the moose take and the fish spawning grounds are not where they used to be because of mining. In his village, five houses need to be moved because of riverbank erosion caused by the rapidly changing climate. “This is our store out here,” he says. “We can’t trap or hunt like we used to, so people end up in cities.”

Walter “Chuck” Peter tells us how “the river (ice) goes out earlier and earlier. These days it’s the first week of May. It used to be at least the 20th.” Flocks of geese used to fly over Gwich’in Zhee for two weeks, but lately it’s only for three days. Hunters have to go north to pursue them, and fight ice in the channel, which is dangerous due to increasingly early melt times. “Sure we adapt,” he says. “We’re Natives.” But without the caribou, moose, birds and fish, “we wouldn’t be able to survive on this land.”

We also hear from some Inupiaq Eskimo People. I’m well aware of the history of the government and corporations trying to pit the Inupiaq against their Gwich’in neighbors, just as Peabody Coal tried to cause conflict between the Navajo and the Hopi in Arizona. Because the board of the Inupiaq Arctic Slope Regional Corporation (ASRC) favors drilling in ANWR, they argue that their interests should supersede those of the Gwich’in, who live farther away from the coastal plain. Stanley Riley is one Inupiat who doesn’t see it that way. “Our responsibility is to protect the Porcupine Caribou Herd,” he says. “We made a vow to take care of each other…It’s a corporation vs. tribe issue, not Gwich’in vs. Inupiaq. We are connected by the Porcupine Caribou Herd.”

Stanley talks about the changes in his land farther to the north. He’s only 34, but has already seen the coastline recede about a mile. He first went whaling in 1997 as a rite of passage for a young man, but now the whalers “can’t find fresh water sources coming out of the ice and have to haul water.” After seeing a polar bear drowned on the beach, he didn’t want to hunt them anymore. “We’re trying to save this place for generations to come.”

We get another perspective from Siqiniq Maupin a young Inupiaq/Italian/Irish woman from Utqiagvik (formerly known as Barrow). She says she is “one of the first generations to not know our language, or ‘real food.’” A couple of years ago, she recognized how disconnected she had become from the land and her ancestry. When she heard the sound of traditional drums at a relative’s funeral, she cried. “I didn’t know I was searching for that my whole life.” She soon stopped working for ASRC, and stopped drinking, and has since become deeply involved with Native Movement in Fairbanks. She is concerned about the pollution that has affected her people due to the oil industry: “asthma, cancer, sick fish, sick caribou…twenty-year-olds with stage four cancer, children with leukemia. The extractive industries are killing us.” Like Stanley, she sees the interests of Inupiaq and Gwich’in as coinciding. “We fight with love,” she concludes.

Princess Johnson reminisces about her visits to Fort Yukon while she was growing up, and how much she learned listening to her elders. She teaches us the term Shilak Naii, which means “relatives, all my relations, including the river,” and gets the audience to repeat the word enthusiastically. She emphasizes the lesson of gratitude that she learned from her elders, about “thanking the fish” and “thanking the water.” She has a sense of continuation: “All of our ancestors for thousands of years have traveled this way…we all have a role to play to protect Mother Earth at this time…We have the solutions and we need to remember to dream.

Kathy Tritt, an Elder from Fort Yukon, tells us that the caribou’s migration route has already changed and moved farther away from the village due to climate disruption. The oil companies already “have 95 percent (of the coastline) and there’s this little 5 percent (the Arctic Refuge) and they want that, too.”

Timothy Roberts, at 22 the youngest chief of the village of Venetie, talks about the Gwich’in value of sharing. This past year, there were lots of black ducks in Venetie, but they were scarce in Fort Yukon, so they shared ducks and geese among the villages. The traditional value of sharing is an adaptation that will serve the people well in this time of climate disruption, which will increase even if drilling in ANWR is prevented.

Bernadette and the legal team fighting against drilling summarize the current situation. An environmental impact statement is required by law, but the BLM held a meeting in February with almost no notice to the Gwich’in People. The BLM position is that there is “no impact on the Gwich’in because they don’t go there, Bernadette says, “but the caribou do.” In addition to the Gwich’in Steering Committee, the Gwich’in tribal governments have now become involved in the struggle, as have the general public throughout the US. Some 1.2 million comments were submitted on the EIS from Americans across the political spectrum, overwhelmingly against drilling.

The best hopes lie in legal challenges and in HR 1146, the Arctic Cultural and Coastal Plain Protection Act, a bipartisan bill in the US House of Representatives that specifically protects ANWR from oil exploration. A hopeful sign was the late June passage by the House of a Department of Interior appropriations bill that at least prevents the sale of Arctic Refuge oil leases at rock-bottom prices. On July 31, the Gwich'in Steering Committee joined three environmental organizations in filing suit in the US District Court in Anchorage against the US Department of the Interior, alleging that the department broke federal law by failing to make plans for oil leasing in the Arctic Refuge public information.

We also get the scientific overview. It’s the dire science I’ve been reading about for months from various sources including the Alaska Climate Action Network that sponsored the climate rally I attended last September in Anchorage. Since then, Alaska had its warmest spring on record. The changes are coming so fast I can barely keep up. Since I started writing this article, Anchorage and other cities, towns and villages in Alaska have suffered record-breaking heat, including an unprecedented temperature of 90°F in Anchorage. Both Anchorage and Fairbanks are plagued by heavy smoke from wildfires.

We also hear from Dr. Joel Clement, famous as the career biologist working on Arctic climate change adaptation issues for the Department of the Interior who blew the whistle on the current president and on former Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke after he was suddenly reassigned to the accounting office that collects oil industry royalty checks. Joel, now a fellow at Harvard, tells us the Arctic is changing far faster than climate models predicted. Recent estimates are that “50 percent of the permafrost will be gone by 2070.” After years of studying the Arctic, Joel believes in the resilience of the people: “the keys are in the hands of the Indigenous people learning to adapt…I know we will prevail because of the Arctic Indigenous capacity for transformation.”

Dr. Brie van Damm, an atmospheric chemist based in Fairbanks, talks about how environmental monitoring projects are bringing communities together, and that the data is owned by those communities. She explains the feedback loops occurring in the Arctic. The loss of sea ice means loss of albedo, the ability to reflect heat and sunlight back into space. That in turn increases evaporation, which increases cloud cover and humidity in the atmosphere. The Arctic has warmed 2.5°C (4.5°F) in the past 40 years. Among other effects are “earlier and more intense flowering seasons in the Arctic, which lead to a timing mismatch” with the insects and birds dependent upon these flowers for food.

Stanley G. Edwin, a Draanjik Gwhichyaa Gwich’in physicist and atmospheric scientist, points out already dramatic observable changes: trees that are no longer supported by permafrost fallen in the forest; old water lines moving and water soaked into the ground; tree lines moving north. “We’re at ground zero and we’re not going back,” he says. “Cultures develop and change over time…whether or not the children are hunting depends on what we do here.”

The three-day conference ends on a positive note, with several women from Native Movement leading a short decolonization training. Enei Begaye, a Navajo woman who has married into the Gwich’in, explains Native Movement’s approach: “People power is the way we make change. The people closest to the problem are the people closest to the solutions. We don’t tell communities what to do…We believe the local people have the solutions.”

The decolonization training, developed by a Yup’ik woman named Rose Dominick, requires us all to participate for it to work, for us to learn about historical trauma. First, a traditional drum is put in the center of the circle, representing the spiritual ways of the people and the connection to Mother Earth. The children are asked to gather in the inner circle. Some are shy and have to be coaxed. The Elders are in the next circle, and though I don’t quite consider myself a senior, I join them. Behind us are the women of mothering age, and behind them the men of fathering age, who are meant to be the protectors.

First, the drum, the spirit, the center, is taken away by colonization. Then the children are removed from the circle, sent to boarding schools. Illness and massacres randomly take out Elders, women and men. The security and the weaving are gone. The circle is broken, the culture frayed. It begins to heal when the drum is brought back, the children are brought back, and the Elders who still know the language teach it to the middle generations and to the children.

All week, many of the Gwich’in Elders have been involved in a language intensive at the high school. Younger Gwich’in are making an effort to reclaim their language and culture. Bernadette and others introduce themselves in Gwich’in, as she does in the accompanying video. The people here are strong in their dedication to family and culture, and strong in their resolve that drilling in the Arctic Refuge will never take place. I recently heard Bill McKibben say that the more activists delay pipelines and other oil and gas infrastructure, the better “the odds are it will never be built.” The market, climate disruption, or both will engulf us like a rising tide. Better that we use our resources — financial and creative — to seek out solutions to the climate crisis than waste them on infrastructure that will only destroy what precious nature we have left by extracting fuels that will soon be irrelevant and outmoded in the name of short-term gain for a few humans.

At times, I feel that the world’s Indigenous people on the climate crisis frontlines are the thin line protecting the whole of humanity, the whole of the ecosystem. The people of the Arctic, the people of the Global South, Indigenous people everywhere, and people of color and poor people in every nation — those who have contributed to the problem the least — are the first to feel the effects of climate breakdown. Let’s at least leave the Porcupine Caribou Herd for the Gwich’in. If it survives, perhaps their culture and people can adapt in some way to the changing climate and ecosystem. If the Gwich’in can inspire people everywhere to protect pristine lands and rediscover our essential connection with Mother Earth, who knows what is possible?

To see a video of Mayda Garcia singing the Willow Song, click here.