His book Shooting in the Wild: An Insider’s Account of Making Movies in the Animal Kingdom was published in May 2010 by Sierra Club Books. He is president of the MacGillivray Freeman Films Educational Foundation, which produces and funds IMAX films, and he is also a professor on the full-time faculty at American University where he founded and directs the Center for Environmental Filmmaking at the School of Communication. Prior to becoming a film producer, he served as chief energy advisor to Senator Charles H. Percy and as a political appointee in President Carter’s Environmental Protection Agency.

My motivation was that I'm going to be sixty-three next Wednesday and had some questions about my work. I'm very proud of it – I think working on the environment is very important – but I'd also had some doubts about it. I'd seen certain things, heard certain things, done certain things, that when I looked at them or heard them or saw them, I felt troubled. Over the past ten years, I'd wanted to put these thoughts into writing. I've given a lot of speeches at conferences that were sometimes greeted with hostility – people get upset when they are criticized. If I get up at a conference and say that there is no evidence that these films produce any real, measurable conservation, people get very upset with me. I wrote the book to bring these issues to the public, to launch a campaign to clean up the wildlife filmmaking industry.

What would you say is our role as an audience, as a consumer of these films? What recommendations would you have for us?

To be skeptical, so that when you see a wolf on the screen you don't assume it's wild and free-roaming. I hope the book makes you say to yourself, "Was it a game farm?" When you see a grizzly bear feeding on an animal, I want viewers to ask themselves how the filmmakers got that shot. Was it real or set up? Was it done in an enclosure? When you watch a film on environmental issues, wildlife issues, I want people to say, "What's the message? Is there a conservation message? Was the film just put out there to distract me, or was there something of value? Or was it just a piece designed for money, for the network's bottom line?" I'm hoping that people will ask more questions or demand that networks produce higher quality films.

One of the chapters of the book talks about "nature porn" and "fang TV", and that seems to hold great appeal for both some filmmakers and some segments of the audience. What do you think most people are looking for when they see these films?

A twenty-something male settles down on the sofa after a long day's work and turns on this type of show looking for just pure entertainment, hoping for violence and excitement and animals copulating and things like that. On the other hand, parents who watch Animal Planet with their kids want the whole family to be entertained but are also looking for some value from the show, a portrayal of the natural world and how it works. There are different motivations; it's hard to generalize. When I watch one of these films, I'm looking for a conservation message. I'm looking to see that animals have not been harassed. I'm also looking to be entertained.

On the other side of the camera, what do you think is motivating filmmakers who are making the films? Given the increased competition, are they focusing principally on what the audience wants, or do you think there are other motivations going in?

I think that what motivates filmmakers is paying the bills. Television is a very money-driven system, and when networks like National Geographic hire someone to make a film, that filmmaker is going to do whatever they can to please the boss. I think filmmakers are a mixed bunch, but the general answer is that they will make a film that will satisfy their clients. They may be passionate about some films, like An Inconvenient Truth with Al Gore, for example, but most people are just trying to earn a living while promoting conservation.

My instinctive answer is, generally, no, but I would have a hard time proving that, for example, Bear Grylls killing animals for TV. In Untamed and Uncut the animals are demonized and made to look unnaturally menacing and man-eating, or Blue Planet which has no mention of conservation. Sometimes you can begin to worry that maybe the films do more harm than good, but I think that overall they are a plus because they bring us in touch with the natural world.

You outline many recommendations in your book. Would you mind going over them again? What do you think could be done to change the incentives for audiences or filmmakers, so that conservation comes more to the forefront as a goal in these films?

I'm launching this book and a campaign to try to reform the wildlife film industry and to raise people's awareness. If Discovery and National Geographic and Animal Planet and BBC know that there are people out there who care about this, they will decide not to use game farm animals, or allow any harassment of animals, or they will explain where they got their shots. I think if the public demands it, they will be responsive. They behave the way they do because they can get away with it.

Would you mind talking a little bit more about your campaign?

In chapter eleven of the book, I've laid out eight steps for reforming the industry. I'll be away next week at the Blue Film Festival in Monterey, California, and I'm campaigning for reform at various festivals and conferences around the country, where I'll be talking about my book and getting people to think about these films – how they're made, why they're made, and what they achieve.

What are you proudest of in your career?

One thing I'm proudest of is Whales, the IMAX movie I co-produced with David Clark. There are some questions about it, but overall, I think it's a very good film. I think whales are fantastic animals, and we need to save them by ending whaling. That film, among many others, certainly helped raise people's love and appreciation of whales. I'm very proud of most of the films I've made because of what the films I've been associated with have done to promote conservation.

One of the biggest challenges is just trying to raise money to make films. Another challenge is that when you are in the wild, it's very tempting to take the easy way out. It's a challenge to avoid doing anything unethical when you're out in the field alone taking pictures, even though you can get away with it because no one is looking at you. You know you can get close to animals and harass them to get the picture you want. You can interfere with things you shouldn't interfere with. You can get close to bears and bother the heck out of them, and it's not good.

What would you want audiences to take away, assuming that a film successfully promoted a conservation message? What would you want the next step to be for people?

I want people to come away from a film and say, "That was wonderful," and then blog and tweet about it, go to the film's website, and read the book. I want people to watch the film and become mobilized to do something about the issue highlighted in the film.

Given the environment of increased competition, you discussed that sometimes this can result in pressure to act unethically. How do you see this affecting the future of wildlife films? Generally speaking, where do you think the industry is headed right now?

I think it's headed for a worse state. As I've said before, television is a money-driven system. There is tremendous competition between National Geographic and Discovery, between BBC and other networks. Careers depend on ratings, so the people who run these networks will do anything to get high ratings. At their year-end performance assessment, they're going to be asked how they did on the ratings. If they haven't improved, they're going to be fired. So I don't see a good future at the moment. Unless citizens demand better programming, we will see more irresponsible, sensational films, because that's what gets an audience. That's what is going to continue as good programming, even though it may be unethically made.

We need more grants from foundations, but I don't see more government. I don't think regulations are going to work; they're just going to annoy people. I think what's going to happen is that people who care about the subject are going to let their views be known to the networks, then networks must change their behavior.

Are there any films that you wish you made or that you would like to see made by you or someone else?

Yes, two things. I think the population issue is so important, and yet how often do you pick up the New York Times or Washington Post or Wall Street Journal and see an article about it? The world is close to seven billion people and no one talks about it, and yet it's fundamental to so many problems. So many problems are exacerbated by overpopulation, and yet we don't talk about it enough because it's boring. No one wants to hear about it. One of the things I'd like to do, or see other people do, is produce a persuasive, wonderful film on population, as it is so important. I feel the same way about toxins. We have so many poisons surrounding us from industry and agriculture. We need to be much more aware of that and take steps to prevent them from getting into our food and lungs. We all need to be more aware of the danger of poisons, so we need to produce media on that subject.

You mention that overpopulation isn't the most exciting issue. Do you think there are other reasons why it isn't discussed?

I think we would have a hard time making a documentary on this subject so that it would have some entertainment value while it also teaches us about the problems of overpopulation. I think it's a movie that hasn't been done because people haven't seen ways to make money from it.

Looking back, do you have any major regrets? Would you have done something differently, knowing what you know now?

If I knew back then what I know now about game farms, I think I would have put my foot down and said, "No, we're not going to do that." As I was learning about the business, I was naïve and I made some mistakes. I talk about some of the mistakes in the book. I wrote the book to make it public, so that other people wouldn't make the same mistakes.

I would say go to film school, such as where I teach, at American University, or Montana State University in Bozeman to learn about it. But the key thing is getting a job with National Geographic or Discovery, or with a filmmaking company that produces for those networks. Get the experience. Also, begin to think up the stories you want to tell. Begin to make the film, develop the treatment, and think of where to get the money for it. I would just encourage people to forge ahead and act as if you know what you're doing.

How did you get your start? What pushed you in that direction?

I was looking for a new way to be effective. I testified on the Hill as a lobbyist for the National Audubon Society, and I began to think that wasn't the best use of my time, and that maybe a better use of my time was to influence the people who elected the congressmen and senators in the first place. I got into filmmaking because I had this notion of using television to reach the public, and then the public would elect better people.

What do you see as the end goal of the environmental movement and conservation movement?

I think it's to produce a more sustainable society. We need to reach a society that is sustainable and safe and clean so that our children and their children and grandchildren, and so on, will have a world that is safe and clean and decent to live in, without things poisoning their food, air, or water. They need a world in which wildlife is plentiful and safe from harm. I think the goal is a world where there is economic or environmental justice so that burdens of pollution are shared by all instead of going to the most marginalized of society.

More information:

Trailer for Shooting in the Wild

Center for Environmental Film, Chris Palmer speaks at the 2010 Environmental Film Festival

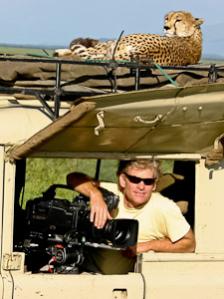

Photos are copyright protected and are used by permission of Chris Palmer. Photographs may not be reproduced without his permission. Copyright information for the photos is as follows: (1) Bob Poole filming cheetahs, photo courtesy of Bob Poole, (2) Kim Wolhuter filming hyena, photo © Barend Van Der Watt, (3) Joseph Pontecorvo filming blue-footed booby, photo by Alison Balance © NHNZ, (4) Brady Barr filming king cobra, photo © Brady Barr, and (5) Doug Allan filming humpbacks, photo © Sue Flood.