Part 2 of a Field Notes series by Caroline Jeffery — click here to go to Part 1.

Despite protective laws, thousands of primates are taken from the wild every day. They are then illegally sold for the exotic pet trade or roadside tourism. And because they are no longer getting the correct nutrition and exercise they enjoy in the wild, many soon die. So what is being done to end their needless suffering? How can this illegal trade be stopped?

This is the story of how I learned that there is hope when I witnessed a brilliant strategy to rescue, rehabilitate and protect primates firsthand.

I stumbled across the Dao Tien Endangered Primate Species Centre on a visit to Cat Tien National Park in Vietnam, which you can read more about in my previous article.

My partner and I joined a band of tourists taking a ferry upstream to a lush green island in the river. Stepping out of the boat onto a rocky slope, we were greeted by a very friendly staff member who would be leading our tour.

She told us that Dao Tien rescues and rehabilitates four species of primates, and that there were currently several gibbons and one pygmy slow loris in residence.

Although primates are protected by Vietnamese law, they are stolen from the wild in staggering numbers. When the centre receives a call that a primate has been spotted outside of its natural habitat — and there is space to house it— a staff member heads out to retrieve it as quickly as possible. From here, the animals are usually released into the 180,000-acre national park across the river. Having already seen a fair amount of animal mistreatment on my trip through Southeast Asia, I was relieved and happy to be meeting some with a bright future ahead of them.

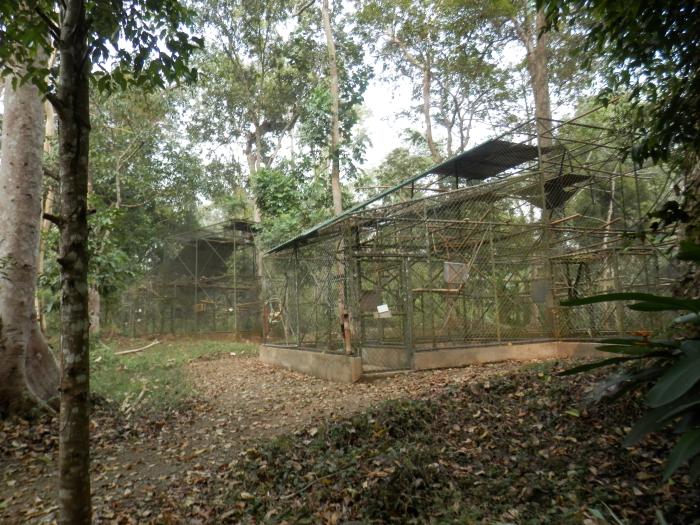

After a short walk deeper into the forest, past dozens of huge yellow butterflies and spider-web tunnels in the grass, we entered a peaceful green area with several enclosures.

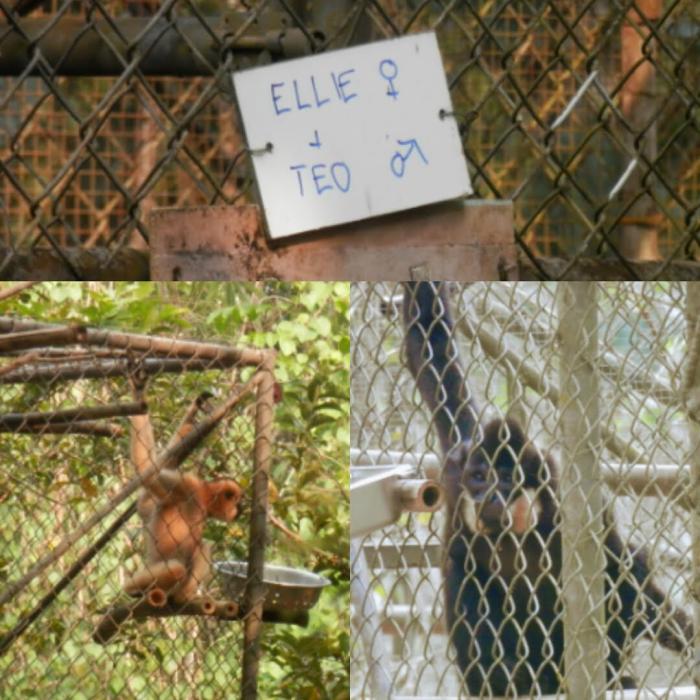

First we met Ellie and Teo, two gibbons with similar stories — and a budding romance. As we approached, the black-furred, golden-cheeked Teo swung to the front of the enclosure, watching us with intense curiosity.

We learned that he was rescued from a house in Bien Hoa City in 2009. Due to spending his entire life in a two-square-meter cage, he had developed a twisted rib cage and a severe case of rickets. Once at the centre, he slowly became increasingly fit by eating a nutritious diet, receiving pain-relief medication and figuring out how to swing between branches in his new home. Unfortunately, his back is still twisted irreversibly, as is Ellie’s curved spine. Neither can ever be released because they would not survive in the wild. Luckily, the two paired together easily and now live happily in a large enclosure with plenty of branches and social contact.

I found myself surprised and impressed by the lengths taken on behalf of the animals at Dao Tien. Unlike my memories of the zoo, we observed them from a fair distance, and were invited to keep our voices low. The goal is to minimize human interaction so they will forget feeling comfortable around humans. I love seeing animals up close, but this was even more amazing. By keeping my distance, I was enabling the animals to become wild again, to help them survive once released. I recognized that to truly keep their best interests at heart, we have to honor their natural way of being.

The next stop on our tour was a watchtower, where we settled in to observe another pair of gibbons. This pair had cleared all the health checks and progressed well inside the initial enclosure, and were now in a semi-free area. Here they will be surveyed until the centre staff determines that they are ready for release. It was astonishing how fast they could move through the trees, swinging with their very long arms, dropping suddenly and then gracefully catching onto another branch many feet below.

As I mentioned in my previous article, two of the rescued gibbons came up very close to us. The mother and daughter gibbons had completed their rehabilitation process and moved into the park, where the mother met a very fine wild male gibbon. Unfortunately, a slight mistake meant the family was approaching human-occupied areas. They had been released too close to an enclosure of rehabilitating gibbons, and were returning to defend their territory. The male gibbon held back to holler at the caged gibbons; the mother and daughter, remembering their encounters with humans, felt comfortable enough to swing right above their heads to eat the spiders living on the building frames. While I felt incredibly lucky to see them, I found myself wishing they’d be more cautious — one day the nearby humans might be poachers!

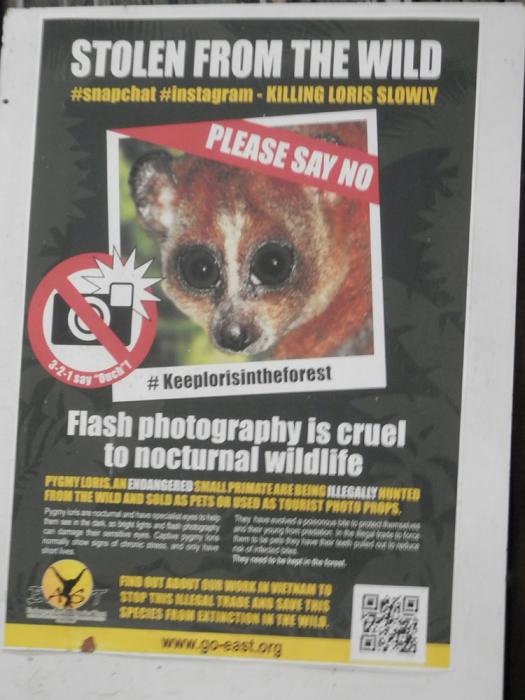

On the tour, there was one resident that I didn’t fully get to see, the pygmy slow loris. I was glad that the centre allowed him to sleep peacefully — we were only permitted to look from a long way away. In the wild, this slow-moving nocturnal primate can travel a distance of two miles in one night as he searches for insects to eat. Once poached from the forest, however, the lorises of Vietnam may suffer the worst treatment of all.

Our tour guide showed us a video of a woman tickling a pygmy slow loris. Do you recognize it?

Far from enjoying the tickling, the loris is holding up her arms because she is preparing to secrete venom from a gland inside her elbow. She would bite, too, if she could, but her venomous back teeth have probably been wrenched out. When this video went viral in 2009, the demand for pygmy slow lorises as pets skyrocketed, and they were stolen from the forest to the point of near extinction. Even celebrities fueled the demand for this deadly trend by including the adorable, endangered loris in their selfies and music videos.

When kept as pets or for tourists to take photos with, the lorises’ needs are misunderstood and unfulfilled. Their big eyes, evolved to see in the nighttime darkness, develop blindness when forcibly exposed to bright sunlight and flash photography. Many die very young, as a result of insufficient diet and infections contracted from being unable to clean their fur as they would in the wild.

Thanks to the work of Dao Tien Endangered Primate Species Centre, our loris would soon be on his way to freedom again. We learned that once the centre’s residents are healthy and ready to be released, they are fitted with tracking collars. This comfortable device enables staff to check up on the animals for one year, at which time the collar drops off automatically.

But what are the chances he will be stolen from the wild again?

The wrestling that goes on between poachers and conservationists is a global problem. Patrolling the park is an option, though violence can escalate as both sides become more desperate. In some parts of the world, both wildlife rangers and poachers are killed on a regular basis. Not to mention that it requires a huge investment of resources to patrol 180,000 acres of land.

It is more effective to invest in resolving the causes of poaching rather than the symptoms. Much of the time, poaching is either a long-held cultural tradition or an economic necessity. Instead of being cast as villains, potential poachers must be included as a necessary part of any possible solution.

With that in mind, the centre offers a viable alternative means of employment in the conflict zone around Cat Tien by revitalizing another cultural tradition — ceramics. Products are sold to park visitors, and all profits go back into equipping and training local families to run their own pottery businesses. The park and centre also employ local people as rangers, rescue workers and rehabilitation staff. This economically sustainable solution involves everyone in the important work of conservation. Having learned all this, I was delighted to take home a beautiful heart-shaped necklace engraved with “Loris.”

Another key to ending poaching is to end the demand by educating tourists and pet-seekers. Awareness campaigns on social media are particularly helpful in informing tourists that animals being paraded on the streets are suffering tremendously, and can be reported and saved. International Animal Rescue’s “Tickling is Torture” campaign, in direct response to the viral video mentioned above, received celebrity backing, helping to inform exotic pet seekers about the plight of the loris.

My visit to the primate centre made me realize how our lives in the west can be tied to the lives of primates in Southeast Asia. Simply liking or sharing a video on Facebook can contribute to the cruel poaching trade. On the other hand, educating yourself, spreading the truth and fundraising for organizations working on sustainable solutions could have limitless positive impacts. It’s up to every one of us to help make sure that poaching becomes a thing of the past.