Childhood’s End

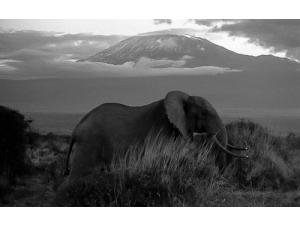

Christo and Wilkinson are a husband and wife team devoted to documenting the beauty of the iconic creatures who share our world and the terrible toll of their loss. Their book, Walking Thunder: In the Footsteps of the African Elephant is a gorgeous tribute, its black and white prints evoking the vanishing herds, like photographs from a forgotten time. But the spike in the numbers of elephants being killed by poachers is reaching devastating proportions. Christo and Wilkinson’s film is an urgent call for global action.

“What needs to be brought to the world’s attention is that the elephant killing has to stop, because the future of childhood is at stake. For their sanity, their wonder, for us not to tell them this is where the wild things were.” Christo’s dark curls mobbed his forehead above round, Potterish glasses and searching eyes. His passion ignited, Christo took me on the journey of the elephant in its mythic, cultural, psychological and spiritual connections to our own species. As a poet and filmmaker, Christo’s language is filled with images and associations evoking the luminous heart of human experience, that which gives it meaning. The deaths and possible extinction of these “walking whales” has far greater consequences for humanity than we can fathom. “From hell’s heart I stab at thee,” Christo quoted from Moby Dick. Like Ahab, in killing the elephant, we kill a vital part of ourselves.

Wilkinson is a measured counterpoint to her husband’s exuberance. She is quieter, resolved, her personal warmth coming across even as she described the commodification of animals that permits their destruction. Explaining the creative difference that animates their partnership, she said, “I think we come from two separate approaches. Cyril is always trying to find the universal ideal and raise it up in a poetic way, and I am trying to find those poetic ideals and bring them back down to a pragmatic, practical, accessible way.”

Wilkinson and Christo’s investigation of the effects of species loss, climate change and globalization deepened through the time they spent with indigenous peoples learning the clashing world views of extractive mining industries versus a storied and ensouled connection to the land. They spent six years studying herders, “cattle people” from Ethiopia through Eastern Africa and down to Southern Africa. “Our peers who are considered “primitive” we consider as holding the knowledge of our future survival. And we are dismissing it,” Marie said.

“We started to learn about the justice system among the Kikuyu,” Marie added, “and their use of the atlas bone of the elephant, which is the largest vertebrae, as an embodiment of ultimate truth. You can’t lie in front of the atlas bone. When there is a dispute going on, first the two try to work it out, then the family tries to work it out, then the community, then the larger community does, then the judges or elders do. If that doesn’t work, then the atlas bone comes out. Because of its unique form, it holds some sort of inherent truth.”

“Elephant” in Hebrew, Christo says, comes from the same root as the verb “to wonder.” That creature in its powerful stature is the spark of wonder to the imagination of childhood and everything in us that yearns toward awe. “Lysander, when he says ‘aaahh’ in wonder about something, it is literally the life breath, the anima, an incredible connection to the life beat.” There is no animal with a greater presence in human history, its mythos representing “the ability to realize our own power and be free.” If we lose the elephant and other of the great four-leggeds, Christo warned, “Something will happen that is irrefragable, irretrievable, irreducible: we will not be fully human. Something will start to corrode in the human soul and heart.” The time to act is now to save all endangered species, especially the elephants, wolves, tigers, dolphins, apes, polar bears. We are veering toward ultimate loss. Christo calls it The Crucifix Moment.

If we do not act, we will lose the combined physical and ecological presence of the great creatures, the elephant, whales and other species within their habitats – which Christo and Wilkinson call the horizontal plane. The vertical plane of the crucifix is the intangible loss of their moral, social and spiritual connection to humankind throughout time.

Slaughter

In March 2012, more than 450 elephants were killed in Cameroon’s Bouba N’Djidia National Park. Tusks were carved away and strapped to the horses of marauding Sudanese invaders, the bodies of the elephants left to rot in the sun. President Paul Biya finally authorized military intervention in the park, but by then, more than half of the indigenous elephant population had been killed. A month later, in April 2012, helicopter-borne poachers massacred 22 elephants, hacking off their tusks and genitals, in Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

According to an analysis by the conservation organization Tusk Trust, up to 35,000 elephants were slaughtered in 2011, roughly 10 percent of the entire population in Africa.1 If the killing continues at this rate, there will be no more elephants roaming the plains and forests of Africa by 2020. This is the price of greed for white gold, the blood gold: ivory. John E. Scanlon, the secretary general of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), commented on the Cameroon massacre: “This most recent incident of poaching elephants is on a massive scale, but it reflects a new trend we are detecting across many range states, where well-armed poachers with sophisticated weapons decimate elephant populations, often with impunity.”2

The numbers are chilling. Twenty years ago, there were more than 100,000 elephants in the Democratic Republic of Congo, now there are fewer than 5,000. In Chad, there were 3,800 elephants recorded in 2006. Five years later, only 400 remained. Gabon, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Tanzania are losing thousands every year. Sierra Leone lost their last elephant in 2011. Senegal has single digits. Even Kenya, with a zero tolerance policy for poaching, is losing its herds at a rapid rate, and Jomo Kenyatta Airport has become one of the main hubs for smuggling ivory into Asian markets. Elephant poaching is funding Al-Shabaab, an offshoot of Al-Queda that controls most of Somalia. Raiders cross the northern border to Kenya’s Arawale National Reserve, a designated conservation area, to kill.

The demand for ivory is insatiable. This is not the first time gross massacres of elephants have decimated their populations. From the 1970s to the 1980s, elephanticide wiped out half of Africa’s elephants, bringing the number down from 1.3 million to 600,000. Today, there are an estimated 350,000-450,000 left on the continent. Seventy percent of those animals live in unprotected areas of the 39 range states designated as their habitat. Even the herds in national parks are not safe, and the few human rangers patrolling vast areas become collateral deaths. Alex Shoumatoff, in his heartbreaking article for Vanity Fair3 titled “Agony and Ivory,” bears witness to the slaughter, and traces the illegal trade from point of killing to smuggling routes, to fraud at point of sale. He states that an average of 45,000 pounds of ivory is seized annually, representing 3600 elephants. That is the tip of the iceberg.

The driver of this blood trade is unmistakable. “The reality is that the Chinese lust for ivory has taken over the situation in Africa,” Christo says. Carvings of yiang ya – elephant tooth – formerly the proprietary mark of the Imperial Court is now a coveted symbol of wealth for the rising middle class. Although the Chinese dominate the demand, it is also sold in tourist spots in Thailand, Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam and Cambodia. Ivory is found in temples and homes as a sign of status, a symbol of power.

As Chinese workers have flooded into Africa to erect dams, bridges and roads, poaching has spiked. The profit is enormous. Forty U.S. dollars for a kilo of ivory paid by a broker in Africa becomes $1,800 a kilo in China, and the Chinese government also participates and benefits from ivory merchandizing. Although international trade in ivory was banned in 1989 with the agreement of the 175 countries participating in CITES, a later decision to allow auctions of stockpiled ivory has had devastating consequences. In 1999, Japan was granted an approved buyer status, and in 2008 China was added. The theory was that allowing auctions of older legally harvested ivory would undercut the black market. Instead, the Environmental Investigation Agency report stated in March of this year, “The decision by CITES to allow auctions of ivory stockpiles in Asia has not only failed to eliminate poaching but actually stimulated the illegal ivory market.”4

CITES has no enforcement power and the watery language of its recommendations has done little to stem the red tide of the ivory trade. They suggest that “a review of China’s internal ivory trade protocol to determine whether there are possibilities for illicitly sourced ivory to leak into the legal ivory trade system would be welcomed.”5

It is a holocaust. “Nobel Peace Prize winner and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel told us personally that someone needs to declare the slaughter of elephants as an urgent moral imperative,” Christo said. “The Samburu say that there is the seed of a human being inside each elephant. Of all the beings in the world we have the greatest relationship with the elephants.” With their intelligence, clans and culture, emotions, response to death, and self-awareness, the elephant might be the species most like our own. Killing an elephant is murder.

“The Chinese people need to understand that an elephant is killed in order to get that ivory,” Marie said. “If they just knew that 95 percent of the ivory they’re getting is from an elephant slaughtered and left to rot in the bush. A mother is killed and the baby who is still nursing is left to wander and starve to death because the rest of the herd has been scared off. But Chinese, like Americans and their hamburgers, don’t really think about where those trinkets are coming from.”

A World Without Oxygen

When my father’s friend Andrew Torschia, a stringer for the Associated Press in Africa in the 1960s, opened his large palm with this gift it did not occur to a child that an animal was killed for it. I pictured the mythical elephant burial grounds of Ramah of the Jungle, an innocent offering from one species to another, as if the elephant itself did the giving. Now I know better; ivory equals murder.

That elephants show many human attributes is well-known. They have a sense of family, individual personalities. They show tenderness and anger and compassion and friendship. A popular YouTube video catches the joyful reunion of Jenny and Shirley, two circus elephants separated for 22 years and finally brought together again at the Elephant Sanctuary in Tennessee.

Another touching story is making the rounds on the internet. Lawrence Anthony, a South African insurance and real estate executive, gave up his lucrative career to help animals. He was best known for two of his efforts: rescuing the inhabitants of the Baghdad Zoo from certain death; and relocating a herd of rogue young elephants onto his large property, the Thula Thula Game Reserve. Eventually, the threatening adolescents calmed down and responded to Anthony’s care. Because of an increasing number of tourists visiting the reserve, Anthony in later years distanced himself from the animals. He did not want them too accustomed to people. Anthony died this past March, and his family reported that the elephants, which had not passed near Anthony’s home in over 18 months, have been visiting every night, as if paying homage to the man who had saved them. They know what death means.

Christo and Wilkinson’s film Lysander’s Song brings together the elephant and childhood. Elephants figure hugely in children’s imaginative repertoire. Marie listed some: “Babar, Baggypants, Dumbo, Horton – the big, loveable creature. They each embody a different aspect of the elephant – Babar being the most diverse and wisest.”

Addressing the issue of poaching from the point of view of children highlights the shocking contrast of innocence and murder. For adults with our own overwhelmed compassion – crammed with information and exposure to global injustice – childhood is the way to connect deeply with this endangered species.

I went to visit the elephants at our small Albuquerque Zoo. These Asian elephants lack the majestic tusks of their African cousins but are equally endangered by habitat loss and increasing conflicts with people in the most populated area of the world. Only about 25,000 of them remain. I noticed their high foreheads and folds of skin, the downward crinkling around their black eyes. Daizy, a 1000-pound, adorable 3-year-old baby, entertained the crowd by bathing in a pool. She sipped water into her trunk and then stepped away, rolling in the dirt to keep cool.

Parents pointed Daizy out to their children, laughing and delighted. The dust glinted gold off the soft hairs on her back, while the mother, Rozie, paced restlessly in the cage. These elephants are enjoyed in their captivity because we believe somewhere else they are wild and free. But for how long?

Christo said, “At the end of our film, a ranger, a guard, says something very very very special – and he knows, because his grandfather was killed by an elephant, and you’d think he would be angry, but no, he’s out in force knowing that was an accident, and it could happen. At the end of the film he says, ‘a world without elephants is like a world without oxygen.’”

I watch the group of people walk away from the elephant exhibit, hurrying on to catch the next animals. They are most likely oblivious to the immediate threat to the survival of this species. They think there will always be elephants.

To purchase some of Christo and Wilkinson’s amazing photos seen here, please visit our photo gallery On the Wild Plains. All images are copyright protected and may not be reproduced without permission. Photos are courtesy of Cyril Christo and Marie Wilkinson.

1 Chief Executive Charles Mayhew as quoted by MSNBC, April 30 2012

2 CITES Press Release February 28, 2012

3 August 2011

4 March 26, 2012

5 From the “Status of Elephant Populations, Levels of Illegal Killing and the Trade in Ivory: A Report to the Standing Committee of CITES. Document SC61, August 2011