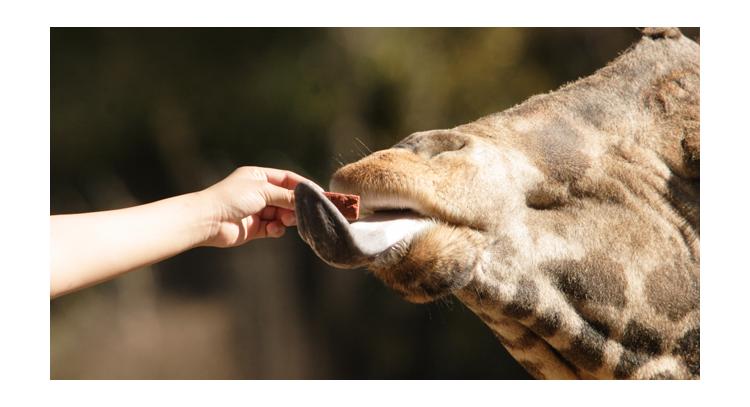

Interaction between a giraffe and a child—something that is allowed in some zoos, but generally not encouraged. Photo courtesy Ian Vorster.

Four years ago, I was living with a couple of friends in Shenyang, Northeast China. We spent a lot of our time exploring old ruins, knockoff shops and other tourist traps throughout the industrial city. Within about six months, we had visited most of the interesting spots in the area. Lacking anything better to do, we took off for the zoo, about an hour bus ride from the city.

I was pleasantly surprised to find the zoo less cruel and archaic than expected (China is not known for its animal welfare record). It contained many of the same elements found in a typical American zoo: animals, gift shops, giggling and squealing children, cafeterias, etc. Most of the animals had reasonably sized enclosures, but there were some glaring exceptions. For example, a photo booth with a stressed out macaw missing half of his feathers, and I heard speculation that the zoo was making wine out of tiger bones.

Of all the things I saw that day, the animal that stands out most in my memory is the polar bear. He only had a 10 feet square cage, with a tiny pool and a little faux rocky area to pace on, I would later learn that the range of the average wild polar is about a million times larger than its zoo counterpart. My Jake and I stood in front of that exhibit, watching this massive, gorgeous, powerful animal reduced to a neurotic, pacing, miserable creature. He would swing his head and walk from one end to the other: back and forth, back and forth, back and forth. We watched until we couldn’t stand the bear’s torment any more, and walked away quietly.

“Zoos are so pointless and cruel, they’re just a way for people to make money off miserable animals,” said Jake.

“I don’t know, I mean, this zoo is pointless and cruel, but I actually think that zoos can be educational, or at least expose kids to something that they’ll care about later in life.” Even as I said it, I doubted myself a little.

Jake was more realistic, “Look around, nobody here is going to be influenced enough to actually make a difference or do anything, the same cycles will continue, and habitats will continue to be destroyed, animals will be continue to be decimated and nothing is going to change, no matter how many people come to this zoo.”

I disagreed, I wanted to do something to help animals and save habitats, and I think that’s at least partially influenced by visiting zoos as a kid.

When our conversation was over, and we were watching the piranhas devour some unknown carcass, I knew that I had to dedicate myself to making some kind of difference, even if only to prove Jake wrong. Is Jake right, are zoos really just exotic animal farms used to profit from captive species, or if they are actually conservation and educational hubs, where people can be exposed to animals and learn about the plight of our most endangered species.

Zoos are not what they used to be. Many zoos have replaced their barren, gray, concrete enclosures with elaborate, lush recreations of real-world habitats. In the last 20 years or so, zoos have come to recognize that simply housing animals is not enough. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) has strict requirements for the size and structure of enclosures. The AZA guidelines state that an enclosure “must be of a size and complexity sufficient to provide for the animal’s physical, social and psychological well-being; and exhibit enclosures must include provisions for the behavioral enrichment of the animals.” That’s not to say that zoos are perfect by any means, because to really enrich most large carnivores with naturally large habitats would require massive enclosures rivaling some national parks. Still, efforts are being made to at least engage animals through other means, even when they don’t get a lot of room to roam.

Dr. David Shepherdson, Deputy Conservation Division Manager with the Oregon Zoo in Portland said, “Life in the wild and life in zoos have different compromises, animals tend to live longer in zoos, free of predators.” I guess that might apply to some prey species but it would be difficult to say if the average lion or elephant might appreciate the tradeoff.

An anteater in an AZA regulation enclosure still paces monotonously to and fro. Photo courtesy Ian Vorster.

Dr. Stuart Pimm, Professor of Conservation Ecology at Duke University adds, “Animal welfare has no simple answer, some zoos keep animals in appalling conditions, but most zoos are improving and try very hard to keep animals comfortable. It also isn’t practical to put the animals back, there are more tigers living in captivity now, than there are in the wild.”

Others say that keeping zoo animals at all is cruel. Dr. Heather Rally, a veterinarian with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) supports this notion, “Zoos need to transition out of displaying animals, a larger prison is still a prison, and housing animals won’t make a difference. There are more creative ways to bring children to animals.”

Zoos have become much more than simply collections of rare species. The AZA accreditation requirements state that “conservation must be a key component of the institution’s mission.” Most major zoos in the US are accredited institutions, with a large portion of their resources devoted to preserving endangered species. Some people would argue that zoos rarely, if ever, release animals back into the wild, and while that may be true for mega fauna—large animals, such as lions, tigers and elephants, many AZA zoos have programs with some type of breed and release program. The Oregon Zoo for example operates a Western pond turtle recovery program that has released over 1,800 turtles into the wild. And they are currently working to reintroduce California condors, among other species. The Santa Barbara Zoo works closely with the same program, and with conservation officials in the Channel Islands National Park.

The AZA website lists dozens of other release programs at zoos throughout the country. In some cases, zoos hold the last remaining population of an animal.

Some argue that these programs don’t make enough of an impact. While many animals are well represented in zoos (elephants, tigers, lions), others are highly underrepresented. Dr. Jeff Dawson, the author of this study published in Conservation Biology, and a conservation biologist with the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, says that “just 6.2 percent of all globally threatened amphibian species are held in the 800 or so zoos that are part of the International Species Information System; much less than mammals (23 percent), reptiles (22.1 percent) or birds (15.6 percent).” Reasons for threatened amphibian underrepresentation include other animals being more crowd pleasing, expensive housing costs and susceptible disease transmission among amphibians.

Dr. Heather Rally takes the discussion a step further, “Money toward zoos misses the point, that money would be better spent going directly to habitat conservation.” However, David Shepherdson disagrees, “That’s money that wouldn’t be available in the first place were it not for zoos.” How do we raise money for conservation and habitat preservation if not through zoos? Oregon voters passed a $125 million bond measure in 2008 to greatly improve the habitats of elephants, polar bears, primates and rhinos, for Oregon zoos only.

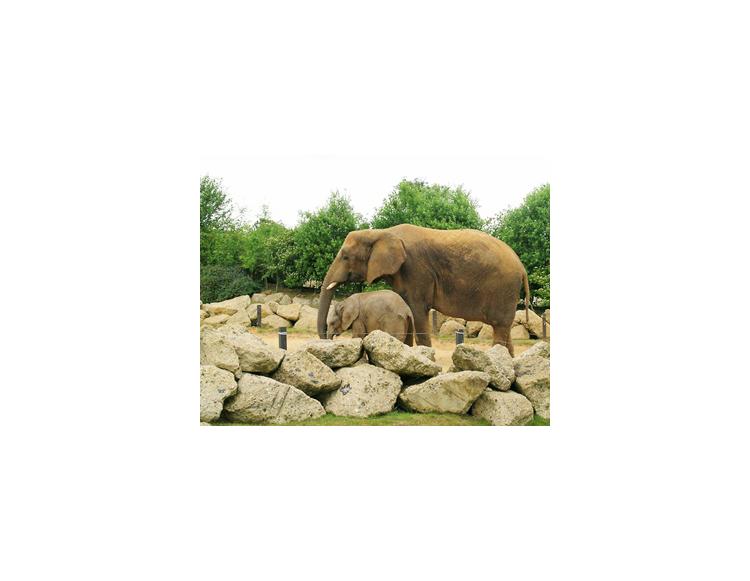

An elephant cow and calf in the Colchester Zoo in the UK. These are the most difficult animals to create a healthy habitat for. Photo licensed under Creative Commons Share-Alike 2.0 license courtesy of Nat Bocking.

Despite respectable conservation efforts, the questions surrounding keeping a wild animal in captivity still remain. Many animals don’t fare well, particularly the largest, most charismatic creatures. Despite constant upgrades and improvements, many elephants suffer from foot issues, and bears and other large carnivores are prone to pacing and similar neurotic behavior. Many animals are still housed in inadequately sized enclosures. The majority of zoos however, have made vast improvements on animal welfare and continue to improve the lives of their creatures.

Also, many zoo animals come from private zoos, where animal care is rarely up to par; without zoos, many of these creatures would be euthanized when their owners can no longer care for them. It’s also worth noting that endangered species cannot be legally imported from natural habitats since the passing of the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

Zoos are not perfect, but they have come a long way from the private menageries of yesteryear. Where once there were concrete enclosures and barren walls, zoos have learned to build habitats that resemble those found in the wild, and conservation has become a cornerstone element for legitimate zoos. But only through public encouragement can zoos continue to improve, and it’s up to us to demand that zoos not only provide adequate housing, but places for animals to thrive.

Zoos can be hubs for critically endangered species, where populations can be revived and released. The loss of our zoos would mean so much more than the loss of private animal collections—it would mean losing the first place that many biologists are exposed to wildlife, where our future conservationists first witness the animals they will grow up to save. It would mean losing some of our greatest zoology research centers, where scientists are discovering more and more about animal behavior every day. Kids can learn about animals through wildlife television programs and books, but there is little replacement for the real, tactile experience of seeing a polar bear or a lion up close. Let’s work toward making our zoos better, rather than making them go extinct.

From former managing editor Ian Vorster: After emigrating with a young family from South Africa to Santa Barbara we became family members at the Santa Barbara Zoo, and visited it regularly. My wife and I had enjoyed the great national parks with their teeming wildlife while growing up in Africa, and we wanted our children to grow up with similar values, if not the same experiences. The zoo was the only way we could do so. Watch this video—it follows my family on a zoo visit, and notwithstanding the many downsides of captivity, shows just how educational and connecting the experience can be for children.