Life as a bird is hard. Life as a seabird can be really hard. Seabirds spend the vast majority of their time in a habitat that provides no drinkable water or shelter, a place that can be as vast and empty as any desert.

We have very little knowledge about where these birds go during their time away from land. Banding has given researchers some insight, but this method requires us to recapture the same individuals elsewhere, or find their dead, often desiccated, corpses. Thankfully, as technology progresses, we’ve come up with affordable methods for tracking individuals.

That’s my job.

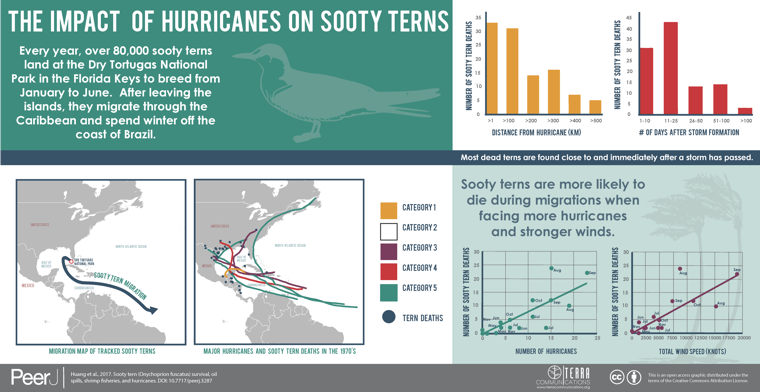

I’m a conservation scientist based at Duke University. For the last four years I’ve been studying a common seabird known as the sooty tern. I work at Dry Tortugas National Park, a small, beautiful set of islands in the Florida Keys that is home to the largest colony of breeding sooty terns in North America.

Every January, roughly 80,000 terns come flying in, turning a small, tranquil island into a swirling, cacophonous vortex of feathers. Put together, the birds make a sound similar to a hundred squeaky toys being squeezed from sunrise to sunset. It’s an amazing sight to behold and a fantastic place to work.

Researchers started banding sooty terns at Dry Tortugas back in 1939, but it wasn’t until 1959, under the supervision of Bill and Betty Robinson, that we began consistently banding terns in huge numbers. Since then, researchers have banded birds every year and we now have records on over 100,000 individuals.

With this information, we can calculate how many birds survive from year to year. When we combine this with tracking technology, we can start to understand how a sooty tern spends its life away from the island.

So the first question is, where do these terns go?

The birds normally leave Dry Tortugas at the beginning of June, moving south past Cuba and the Caribbean. They travel along the coast of South America until they reach Brazil in November, where they spend the winter months in the mid-Atlantic. During the travel period, the birds spend the entire time flying; they don’t see land and they don’t sit for a rest on the water (sooty terns lack oil glands and, as such, they can’t fly if their feathers get waterlogged). It’s a long, tiring trip that rewards those who succeed with a bounty of fish in the nutrient-rich waters pouring out of the mouth of the Amazon River.

One of the biggest challenges during migration — besides the obvious ones — is hurricanes. Hurricane season lasts from July to October and impacts most of the Atlantic Ocean north of the Lesser Antilles. The storms expose already tired and vulnerable sooty terns to some of nature’s most powerful weather patterns.

Birders are often familiar with the phenomenon of storms carrying birds far away from their natural habitat. A lucky few are simply swept along until they can escape the winds and make their way back to their regular migration pattern. For many others, these storms are a death sentence.

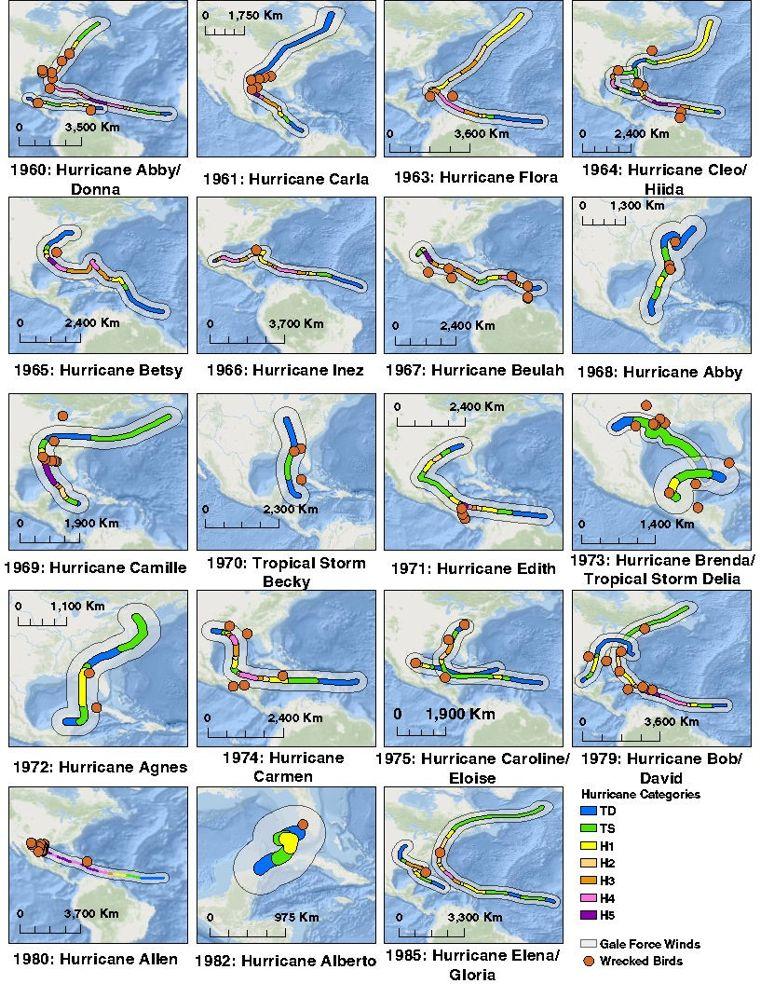

In 1980, the Category 5 Hurricane Allen barreled straight through the Caribbean, blowing down migrating terns like a bowling ball knocking over pins. After the storm had passed, an estimated thousands of birds were found dead along the coasts of Texas and Mexico.

It’s not just hurricanes that cause deaths; less powerful tropical storms can inflict mortalities if they are in the “right place at the right time.” In 1973, Tropical Storm Delia killed more birds than the Category 4 Hurricane Carmen the next year. This is likely due to the fact that Carmen was a late storm that hit areas where most sooty terns had passed already, whereas Delia hit birds right in the middle of their migratory route.

As we move forward, the link between hurricanes and tern death is of increasing concern given the impact of climate change. Hurricanes are formed from the evaporation of warm water. It is Earth’s way of venting off excess heat from the oceans. As the planet warms, climate scientists predict that the number of severe storms (Category 3 and higher) could increase. This means that the chances of sooty terns being in the wrong place at the wrong time is also going to increase.

It’s this mystery that pushes science and society forward: not knowing how our futures will be impacted by the actions of today. What we do know is that the environment is connected. What happens off the coast of South America impacts the environment in the United States. So we collect, measure and analyze data to understand how the world works — and how we are changing it.

Migrating species connect habitats across borders, forming a chain of interdependence. By understanding this sequence of cause and effect, we can understand how to protect and conserve our way of life – as well as the lives of the animals we share this planet with. Understanding science makes life a little easier, for us and the birds.

To read Huang’s paper in PeerJ, click here.

Photos are owned by Ryan Huang, copyright protected, and may not be reproduced without permission.