In the woods, the air is still and quiet. The ground is warm from the sunshine that beats down on the hillside all day, but mostly, it’s dark. The lightest breeze brings the smell of ponderosa bark and lupine from the forest that surrounds your perch. You hear the faint call of a poorwill from another ridge just as the moon is starting to peek over a mountain across the valley. A browsing deer crackles pine needles as she passes close by, startling you. You continue to wait patiently.

Suddenly, you think you hear something. Was it just your imagination? No, there it is again! Distinctly, a four-note set of hoots sounds in the distance up the ridge. Your heart flutters as you grab your gear and sprint up the hillside in your headlamp in pursuit, hoping above all else to hear those four notes again.

As a spotted owl surveyor for the U.S. Forest Service, this is how a regular “day at the office" might go. The northern spotted owl, one of three spotted owl subspecies, has been intensely studied for the last 30-some years after it became the center of the debate over logging in old-growth forests across its range, from British Columbia to southern Oregon. These medium-sized owls require large trees with platforms or cavities for nest sites, a large territory for foraging and breeding, and are highly intolerant of habitat disturbance. In the foothills and mountains of central Washington state, where most old-growth forest was logged years ago, spotted owls are few and far between — and their population is dwindling.

Owl surveys are conducted at night, generally along a series of calling stations about a half mile apart. A battery-operated speaker plays spotted owl hoots, whistles and barks for several minutes while the surveyors listen for any reciprocation.

Our hooting elicits responses from myriad owls outside of our target species. On a nightly basis we may hear or see great horned owls, flammulated owls, western screech-owls, northern pygmy owls, northern saw-whet owls and, of course, the ubiquitous barred owl. If we are extremely lucky we may even hear the low hoot of a great gray owl.

Surveys can only be conducted in dry, calm and relatively cool weather. Spotted owls are already very reluctant to vocalize, so any possible deterrents due to weather or noise pollution cannot be present. When a spotted owl hoots, we will make every effort to find it. If the owl cannot be located that night, we will return the next day in an attempt to locate its roosting or nesting site.

Mousing reveals behaviors that may give an indication of nesting status, among other things. A male spotted owl with a mate that takes a mouse will often bring it to her or call her over to accept the gift rather than consuming it himself. If chicks are present, both parents will likely bring one or more mice to the nest. If a single male eats or stashes a few of his treats, he likely doesn’t have a mate.

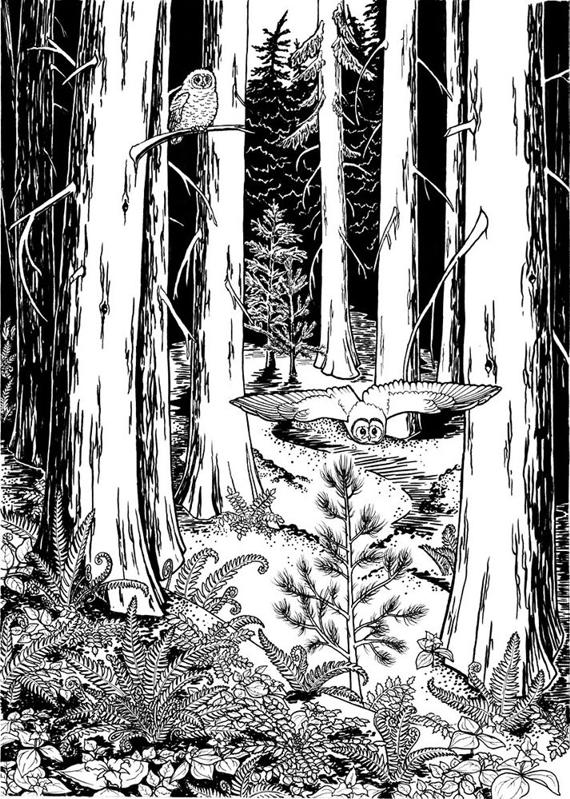

Mundy illustrates her nightly owl watches

Mousing also gives researchers the opportunity to read bands, which are fitted on any spotted owl that a biologist is able to catch. Reading band patterns allows us to know where the bird came from, as well as its sex and age.

Sadly, many of our nightly surveys come up empty-handed. We are far more likely to hear the spotted owl’s worst enemy, the barred owl. Barred owls are very close cousins to spotted owls, and are slightly larger, more aggressive, and less particular when it comes to nesting and roosting sites. They also look quite similar. You can identify a barred owl by its distinct and easily recognizable “who-cooks-for-you, who-cooks-for-you-all” call.

Barred owls made their way west from the eastern United States as a patchwork of fragmented forests was created by massive logging operations throughout the country. While spotted owls prefer primary succession forests, complex undergrowth and canopy structure, as well as large old trees with shaded brooms to build nests, barred owls can nest, roost and forage in second-growth forest and near areas that have been logged. For decades they have out-competed spotted owls, often driving them away from their homes. Five pairs of barred owls can occupy the same territory that would only be suitable for one pair of spotted owls.

On top of all of this, there is very little suitable nesting habitat remaining in the Pacific Northwest for spotted owls. More and more is lost every day through private logging operations. Despite the northern spotted owl’s listing as a federally threatened species, little regard is given to protecting potential nesting sites that happen to fall on privately owned land.

But all is not lost. Spotted owls are still out there, and the fight continues to protect their habitat. Just last summer we found a fluffy, potato-shaped chick with one of our known remaining pairs in the area. They are clearly devoted parents – we witnessed the female dive-bombing a full grown black bear who happened to wander through while we observed the family.

We can only hope that the fuzzy chick won’t grow up to live the rest of its life alone. It’s difficult to comprehend how it must feel to be a rare bird trying to find a mate in a vast world of woods interrupted by terrifyingly expansive clearcuts crisscrossed by highways and dotted with homes. Yet somehow they still manage to do it.

Despite the consistently bad news, the surveys continue — and the drive to understand and protect the magical, rare birds that are spotted owls persists. With continued research and education, I hope that more attention will be given to protecting the fragile habitat that these birds call home.

Photo and illustration used with permission from Brandon Husby and Laurel Mundy, and cannot be used or reproduced.