Harold Joe is a member of Cowichan Tribes, working as a cultural consultant, archeology assistant, resource management technician and documentary filmmaker. His aim is to preserve and teach the values and traditions of ancestral Cowichan culture. He offers his work through public and educational speaking engagements, youth workshops and documentary filmmaking, as well as subcontracting with forestry companies, developers and archeology companies around issues of cultural significance. This article was adapted from an interview with Harold Joe.

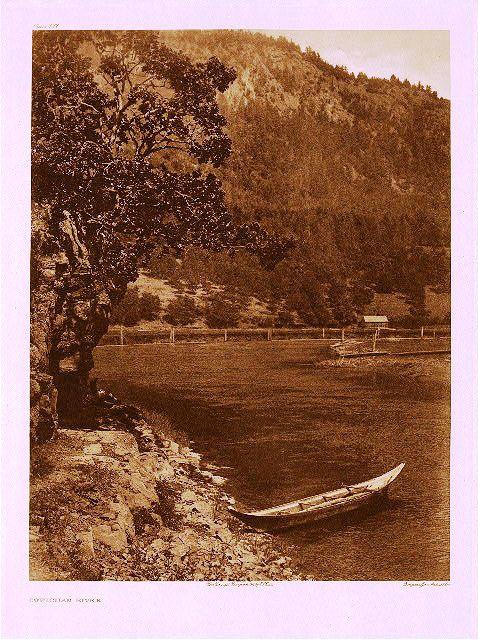

It all started as a survey. I was going to door to door, talking to locals about the water levels of the Cowichan River. We were coming to summertime and the river would be dead dry. Prior to that, there was always water flowing and fish coming in. In late June or early July, we'd start to see the spring salmon come in. That year, we had nothing — and I ended up making my first documentary, Wisdom of the River, about what was happening to the river.

Some friends of mine had recently received a grant and said to me, "We want to do a survey of people, First Nations and non-First Nations, about the water levels. Can you help?” Sure, I said, and started doing just that — while also taking care of my reserve work. They felt I could get some really good feedback, which I did.

At my grandfather's house, I spent about three hours with him, just talking. No recording, nothing. We talked and we talked. He told me about what he saw as a young boy, about the river, what it was like, how it nurtured and what it gave, about the fish and about climate change, which wasn't a factor in his time. We didn't have water shortages, he told me. We didn't have that. Now we look and there is no water.

When I left his place after that interview, a light went on and I thought, “Why aren't we doing a film around this?" I went back to the people I was working for and said, "I just got this great interview with my grandfather. He started telling me the history of the Cowichan River." I described our conversation and they were amazed. I explained how I thought it would be smart to make a film about it, that it would be a great tool for educating young kids and university students. They agreed, and put together a proposal for the film. We only got $15,000, which is not much to make a film, but we were all excited about developing a documentary about the history of the Cowichan River.

I started to seek out people who I thought carried some knowledge and history and tradition around the river. And I found them: five wise Elders who would share what they knew — of course my grandfather was one of them. We started production in late fall of 2001, carrying on through the winter, and then went into the editing of postproduction.

During production, I lost my grandfather. He had been diagnosed with cancer and passed away as we were filming. He was my dictionary for the whole film. I didn't have to go to the museum. I didn't have to go anywhere but to see him and sit with him. He was just so grateful and honored to share the history that he saw happen to the river, what he did with the river, and what they did with the river, the water, the salmon and everything else. When he passed away in the middle of shooting, it seriously affected me and I quit. The crew understood my decision, and I walked away for about two months.

When I spoke to my family, his family, I told them that I was lost, that I was hurting. And they said, "You know what? He would want you to finish this. Come on, Harold, it's a good film. Please finish it." So I got back on board and we completed it. It needed a name, and I knew that it was the First Nations Elders who are the source, the ones who carry all the wisdom. They carry the very basis and understanding of who we are, what we are, why we are, where we are. So Wisdom of the River was born. We premiered it in January, not knowing what the reception would be to its focus on the water, the environment, the fish stocks, the laws, smallpox and everything about how First Nations peoples utilized the river to sustain our families.

It was the Elders who shared all that history, who saw all the changes, such as not even being allowed to harvest salmon out of the river, which we had been doing for thousands of years. Now we needed to have a permit. We're also dealing with climate change and often find ourselves fighting for rights that we should have never had to fight for.

From late April into May, the Cowichan River is dry. Then they close off the weir at the lake and try to figure out ways of bleeding water into the Cowichan so the salmon can return. But the situation isn't getting better, it's getting worse. And it's going to continue to get worse as long as human beings don't look after the system.

There used to be side channels and tributaries that bled off the Cowichan’s main vein, so the spawning salmon could easily sneak through the side channel streams if they couldn't come up the main vein. Then people came with their machines and said, "We're going to cut off that side stream, block it and end it." The river used to meander like a snake, but over time it has been straightened. Well, when you straighten out a river, the flow in the winter moves much faster and the salmon spawning beds don't hold because the water is moving too fast. Has this been proven? Absolutely. Do we need scientists to tell us that? No, we don't. We know because we're stewards of the river and we've seen it.

I still go down there and cut logs in order to open up side channels and streams to allow access for the fish to get through. I've seen the river at three and a half to six inches, with 30-pound spring salmon going through it. I wouldn't even need a spear or a dip net or a gaff to get them. I could kick them out of that water. But I don't.

It's sad to see pregnant salmon with big bellies fighting and struggling through six inches of water to get to where they need to go — they should have an easy journey. Each one is carrying thousands of future salmon. But it’s great to see school kids go down to one area or section of the Cowichan River with little tools, finding ways to help open up an area so that the salmon can come through.

Seals are the biggest natural predators for the salmon. And they're smart — they come in and move all the salmon up into the shallow areas, and then slaughter them. Seals, otters, beavers — all brilliant hunters. There is a family of 12 otters that I've seen for the last 10 years. And they multiply every year. They can clean out a pool quite fast. As stewards, we try to thin out some of these predators to give the salmon a chance, but that is not always well received. And there's poaching beyond imagining. I try to do what I can for the river. The salmon are so important — they not only feed us and other species, but support a whole ecosystem, including the soil and the forest.

Human beings come in with these images and machines, figuring they know what they're doing. That they're smarter than Mother Nature. They end up spending millions of dollars trying to restore something, but it’s is only getting worse.

We now dredge the Cowichan River, pulling at least 300,000 cubic meters of silt out every year, but the following year it's right back. Why? If you look up at the hills or go up into the mountains, there are no trees up there. They're cutting all the trees, clear-cutting everything. So are the logging companies responsible? I'd say so. If you're going to go up into the hills and start destroying the forests, of course there will be serious consequences.

Today the Cowichan is designated as a “Canadian Heritage River.” I think it's ludicrous, and I'm not afraid to say that because I've been on this river since I was a boy. For example, there is still an effluent sewer system bleeding into the river, creating a sewage lagoon down by the low end of our reserve. When it dries up at low tide, you can smell it. Yet we swim there. Kids swim there. Fish swim there. I often hear, ‘Oh well, its treated sewage,” and I ask if that makes it OK to swim in it, or OK for the ecosystem. That sewage lagoon down by the low end of our reserve has been bleeding that sewage since the 50s. Now they’re looking at plans to take that lagoon out, to take that pipe out and run it directly into Cowichan Bay, which is ridiculous and will badly affect the estuary ecosystem. This is the solution they have come up with? Yet no one ever asks any First Nations peoples what they think, which is unfortunate because that kind of collaboration would offer some great solutions.

There are now only two Elders left out of the five that were part of the film production. Having Elders involved in the work I do as a filmmaker is essential to me. I've seen so much happen and wish I could have spent more time with this person and that person, and now they're gone. You'll never hear them share their history and knowledge again. So for a storyteller like myself, it's valuable to get as much information, as much knowledge and as many teachings from my people as I can to carry it on to the next generation.

If I could give any advice, it would be to stop defiling the salmon stock, stop clear-cutting the mountains, stop overfishing the ocean. Stop trying to hide the sun with pollutants. Stop everything. Petrochemical societies are killing everything. I don't want to say this, but everything they have touched is hurt. Mother Nature knows how to heal herself. Allow her that time. As First Nations stewards of the land and the water and the earth, we have to come back to her and help her, not try to show her. She knows what to do. We have to come in as her children and say, "Hey, let's help her."

When I see what New Zealand has done in giving human rights to a river, I wonder, is that something that could happen here for the Cowichan River? Absolutely. That's what we should be looking at.

There are so many things I could say, but I get a little tired sometimes because as an aboriginal person who's been on this river since I was a boy, it's frustrating. It's really hard. I'm trying to pass on everything I know through my work and films, and I go to schools and share with them what I know. I hope that I can get this message through because I'm going to be an Elder pretty soon, watching the next generation behind me. I will see how they carry that on and leave a legacy behind. What is that legacy going to look like?

You can order the Documentary ‘Wisdom of the River’ from Cowichan Tribes here.